Old-fashioned images evoke the complicated history of Black military service

For Black Americans, the military can offer opportunities and the chance to serve—but a legacy of inequality remains.

Fulton Porter wanted to be a doctor, but “I didn't want to go to medical school with any loans,” he says. “And I always had this kind of urge to serve sometime in the military.” So he enlisted.

Porter is part of a long tradition of Black Americans joining the armed services—and benefiting from the economic incentives the military offers. After graduating from Morehouse College in Atlanta, he served in the first Gulf War then applied for an Army program that would pay for 100 percent of his medical school fees.

Now he’s a doctor. “The military provided the assistance that I needed to help me to reach my dream,” says Porter, 53.

From health benefits to education compensation, the U.S. military has historically offered many opportunities for African Americans to improve their economic standing. But it has also given many Black soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines a field on which to serve their country, demonstrate their worth, and fight for racial equality.

Forty-three percent of the 1.4 million troops currently serving are people of color—and over a third of those are Black. Now two of the country’s top military posts are held by African Americans: In June 2020, General Charles Q. Brown Jr. was named Air Force chief of staff—the first African American to lead a branch of the U.S. military—and in January Lloyd Austin, a retired four-star general, was confirmed as the first African-American Secretary of Defense.

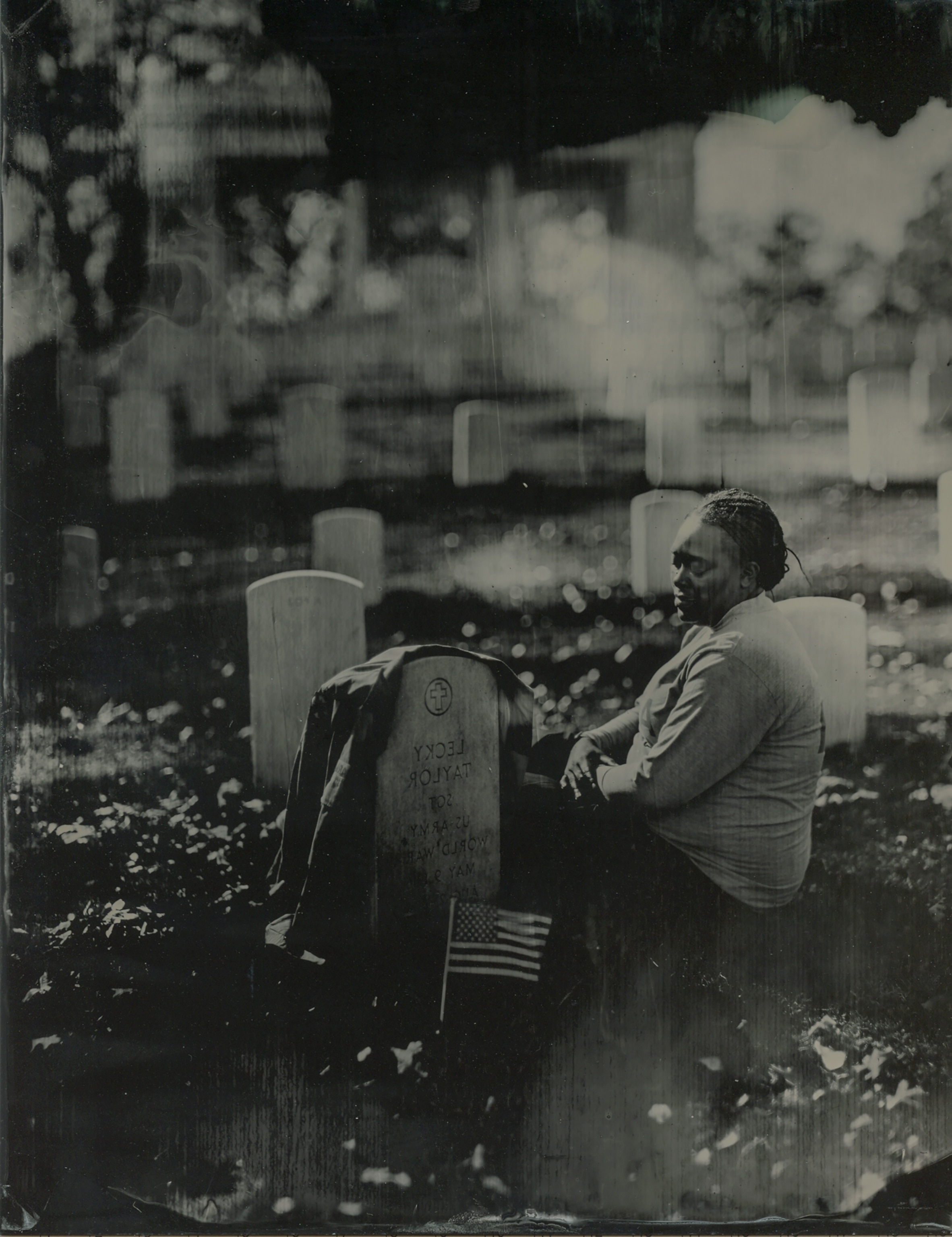

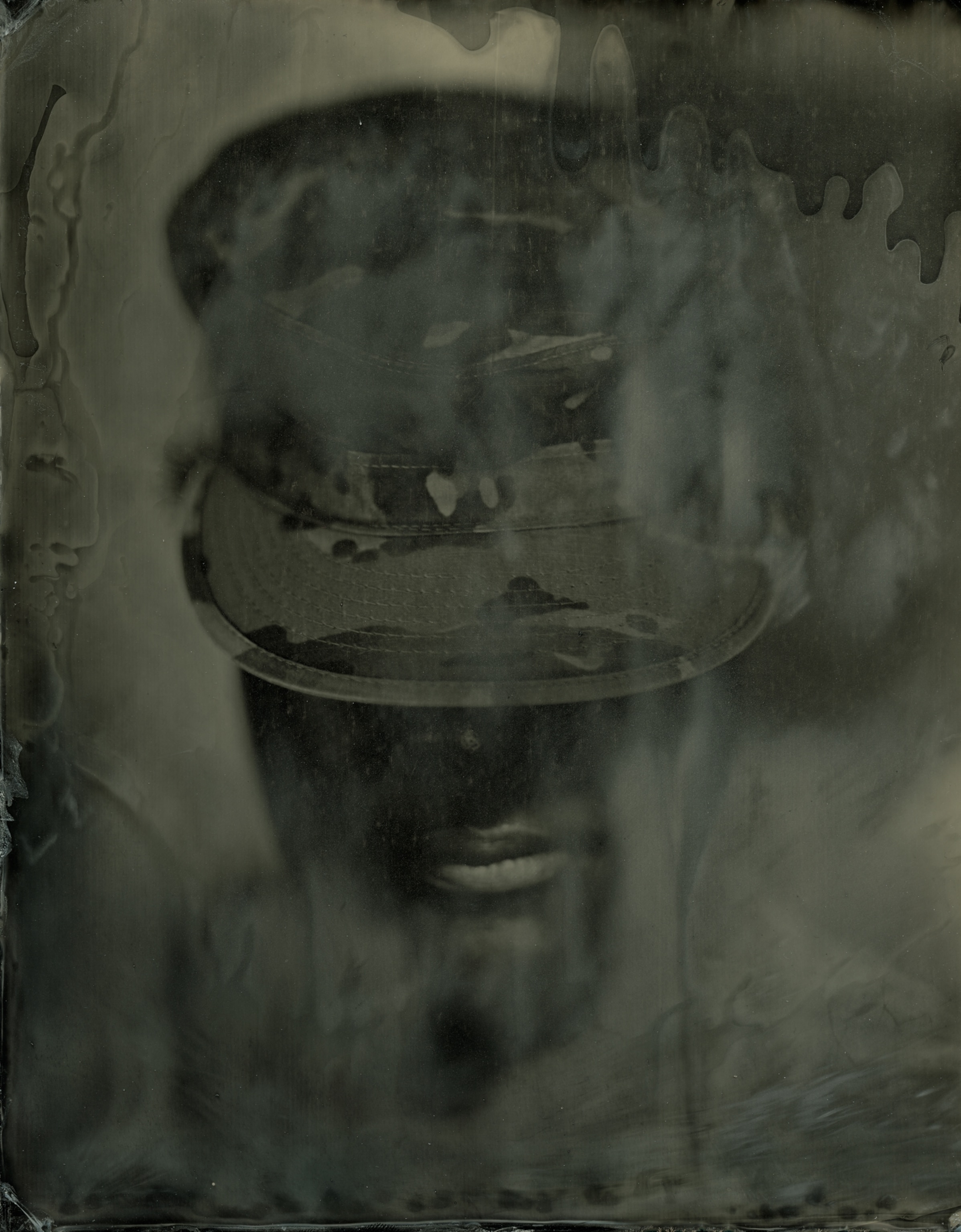

The rich history of Black military service has played out in photographer Rashod Taylor’s family since World War II. Many of his uncles and cousins have been deployed all over the world—from Vietnam to Germany to Afghanistan. Now he’s celebrating their service by including them in his My America project, which highlights the Black American experience. He uses tintype photographs to link the struggles of Black Americans of the past with those today.

“It's a bridge to that same time where people, especially people in the military, are still not treated 100 percent equally,” he says. “I'm trying to just paint this portion of the Black experience or the Black America with a lens that people can look at and one, be aware of the challenges and turmoil that people of color go through. But at the same time, be able to see hope in the future.”

Centuries of service

African-American soldiers have played a role in all of the country’s military campaigns and wars dating back to the American Revolution.

The Ninth and 10th Cavalry, two of four all-Black Army regiments established in 1866, fought on the frontiers of Western expansion, earning the name Buffalo Soldiers from the Cheyenne warriors who compared the fighting spirit of the soldiers to the wild buffalo. "Without the Buffalo Soldiers, the westward American movement would have been delayed 50 years," says Capt. Paul J. Matthews, a Vietnam veteran and founder of the National Buffalo Soldiers Museum in Houston, Texas.

In 1898, the 24th and 25th infantry, the two other segregated regiments, joined Theodore Roosevelt's Rough Riders during the battle of San Juan Hill in Puerto Rico. Two decades later, 400,000 African-American soldiers put their lives on the line in World War I.

But by 1940 there were fewer than 4,500 African Americans in the U.S. Army. Only five were commissioned officers, and 11 were warrant officers. The rest were enlisted men, mostly serving in supply units. There were no black Marines, and only a few mess stewards in the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard. The military wouldn’t be desegregated until 1948.

“You’ve got to remember that this country was very discriminatory, segregated, and there was no change,” said Samuel L. Gravely in a television interview before he died in 2004. In 1944, Gravely became the first African American in the Navy to serve as an officer aboard a fighting ship.

Frank Barbee enlisted in the U.S. Army the day after the Pearl Harbor attack in hopes that military service would help bring about change. “As a Black male of color, I felt that if I fought for my country and shed my blood if necessary,” he says, “when I come back home I would be treated as equal.”

But true equality has been slow to come, especially in military leadership. Colin Powell became the first African American to serve as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff more than 20 years ago, but senior commanders still remain mostly white.

General Brown told the Washington Post in an interview that he’s opened a frank discussion around race and changing the culture of the Air Force. “I really see it as an opportunity,” he says. “The thing I am really focused on and thinking about is to ensure that we do something that is meaningful, that’s sustainable, and then endures well after me.”

Recognition can come, even if it takes a long time. In January 2020 the Navy named one of its newest aircraft carriers after Doris Miller, a Black seaman who was serving as a mess attendant on the U.S.S. West Virginia when it was attacked at Pearl Harbor. African Americans weren’t allowed to serve in combat at the time. Even so, Miller fought valiantly.

Enlisting opportunity

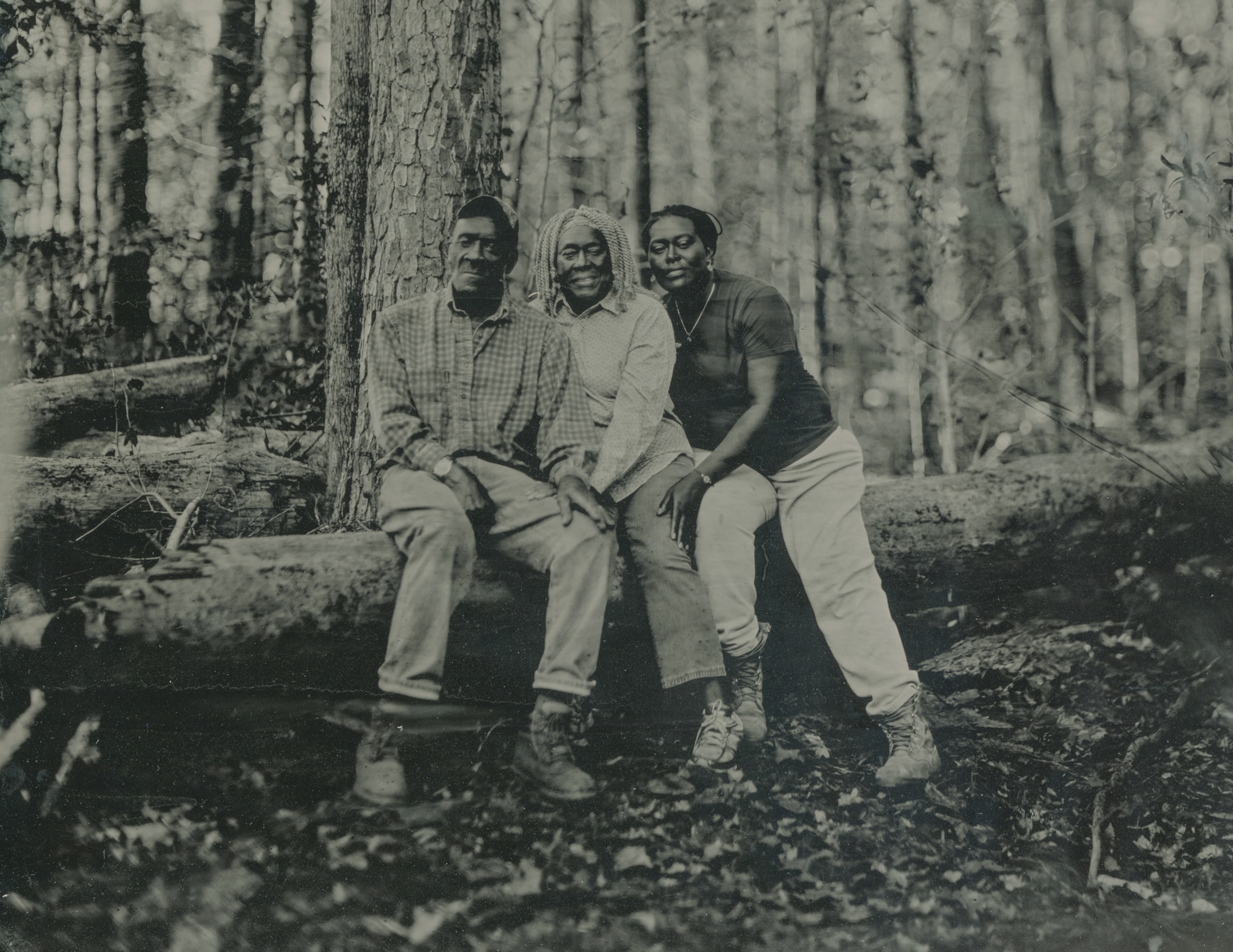

Members of photographer Taylor’s family often reflect on the opportunities provided by the military. His cousin Valerie Ellen Lewis, 43, served in the U.S. Army for eight years, deploying to Afghanistan to work as a medic. She remembers talking with one of her uncles, Mack Lewis, Jr., about why he served.

“My father's family was poor,” says Valerie. “It was 11 kids with a single mom. [My uncle] left not just to give himself better opportunity, but to be able to help his mother raise his brothers and sisters because he was the oldest."

Valerie's older sister Vanessa, 52, also served, deploying to the Gulf for Operation Desert Storm and then to Germany.

Her cousin Larry D. Walker, 52, joined the army as a way to finish school and earn money. “He married his college sweetheart and they had kids,” says Vanessa. Enlisting “was a way for him to be able to finish school and then build an income.”

Matthews believes that the GI Bill in the 1940s provided a major incentive for Black soldiers to continue to fight for their country. Although the provisions of the GI Bill weren’t applied equitably, the bill still helped many Black families attain middle-class economic status.

“You could tell by the graduates from [historically Black] Texas Southern University. During that time the vast majority of those graduates were veterans of World War II,” says Matthews. “Even today, they have special programs. You serve several years in the military and you go get several years in college that's paid for. I think as a young Black person, male or female, if there are no other opportunities for you, then that is a very viable option.”

James Williams is the last living Buffalo Soldier. Despite the racial injustice that he faced, the 85-year-old says he will always be proud of what he was able to gain from the U.S. Army.

“I lied about my age. I had my mama sign some [paper] that said I was 17,” he says. “But thanks to the uniform and thanks to this country, it made me somebody. Until the day I die, I will always be somebody because of what the United States Army has done for me.”

Matthews believes that pride is the entire reason the Buffalo Soldiers fought in the armed services in the first place—to set an example and lay the groundwork for the new generations of Black servicemen and women to follow, such as Lloyd Austin. “I think that this would be well beyond their wildest imagination,” he says, “the Secretary of Defense being a Black man.”

Rashod Taylor is an award-wining fine art and portrait photographer based in Illinois. His work addresses themes of family, culture, legacy, and the Black experience. To see more of his work, follow him on Instagram.

A version of this story appears in the February 2022 issue of National Geographic magazine.