This all-Hispanic Army unit fought in the Korean War. Here’s one veteran’s story.

The 65th Infantry Regiment—also known as "The Borinqueneers"—faced racism and xenophobia from their military counterparts even as they risked their lives for America.

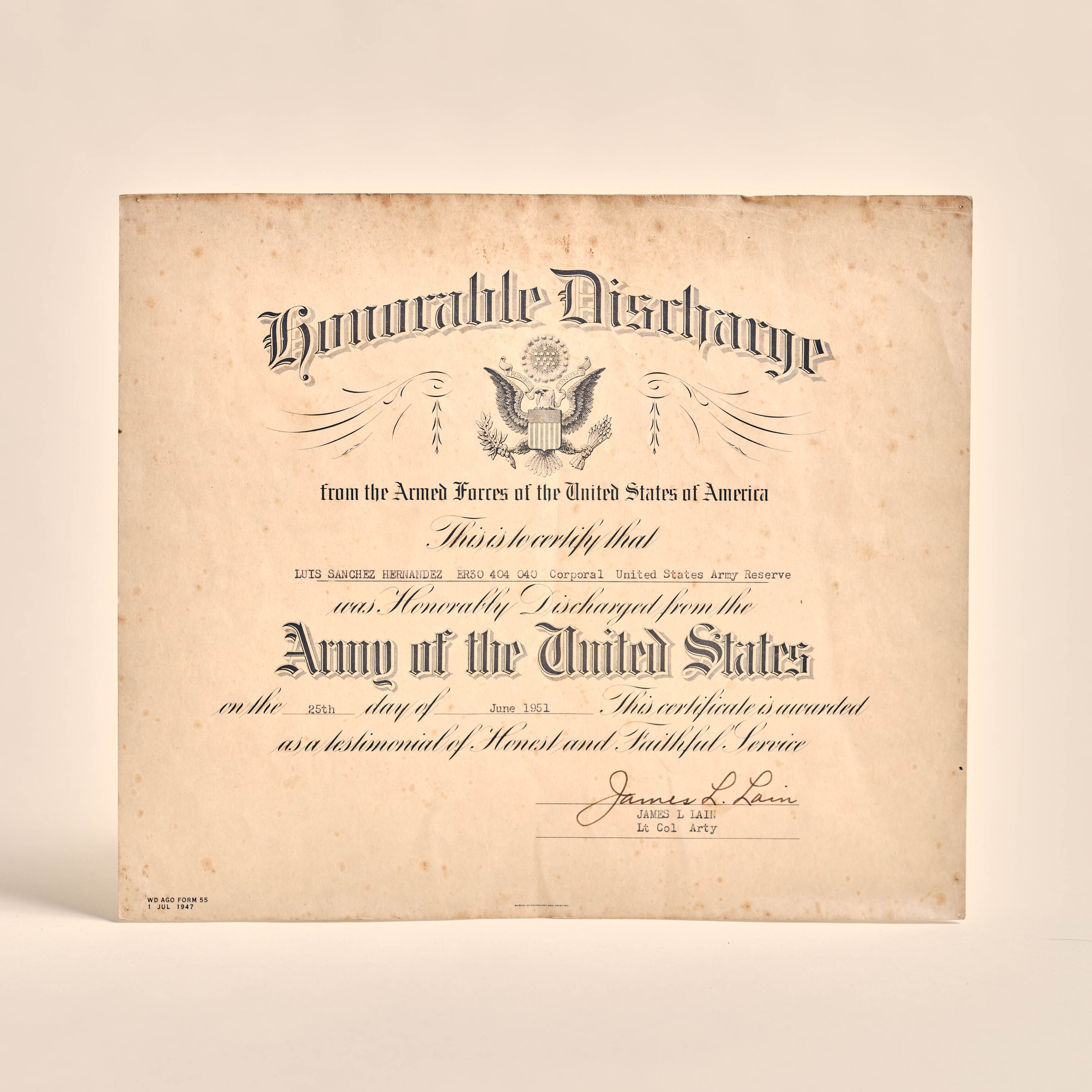

He joined the U.S. Army as a 19-year-old, seeing the military as his only way out of poverty, having left school in the eighth grade to farm to help his family in Cayey, Puerto Rico. Luis Sánchez Hernández served during World War II and was later dispatched to the Korean War. He also joined the movement that supported a political party seeking Puerto Rico’s independence from Washington. It was founded in 1946—just a year after he returned from U.S. service in Europe.

When lymphoma finally took his life, at 89 years old, his final wishes were honored: the casket was not covered with the American flag, but rather the single-starred Puerto Rican banner; his ashes were dispersed on the mountains of his native town in central Puerto Rico, not buried alongside other veterans.

“Daddy was always very proud of his time in the Army, even though he later understood and saw the United States military as an oppressor of our people,” says his daughter, Noemí Sánchez González. “He was proud of all the boricuas (Puerto Ricans) and the work they did.”

Sánchez González is my mother, her father, Sánchez Hernández, my grandfather—abuelo Luis. He was one of the thousands of soldiers of the 65th Infantry Regiment during the Korean War, the only all-Hispanic U.S. Army unit that came to be known as “The Borinqueneers.”

The first group of Puerto Rican recruits that ended up in Korea left San Juan in 1950, explains Víctor Labarca, president of the 65th Infantry Regiment Veterans Association in Puerto Rico. As documented by Noemí Figueroa Soulet in the book, The Borinqueneers, A Visual History of the 65th Infantry Regiment, the soldiers endured a 30-day journey on a crowded warship, which took them first to Panama, then to Japan, and finally to the Korean peninsula—8,500 miles away from their Caribbean homes. For many, it was their first time traveling abroad.

In Korea, the young recruits contended with a starkly different climate—snow and freezing temperatures. The language barrier came in two tongues, Korean and English. The Borinqueneers communicated in Spanish.

Segregated from the other units, they also faced racism and xenophobia from their U.S. military counterparts and officers, even as they risked their lives for the United States. According to U.S. Department of Defense records, at least 713 of the 61,000 Puerto Ricans who were deployed died. Another 2,318 were injured.

The unit’s origin

While the Borinqueneers are best known for their Korean War, the unit’s origins go back to 1899 as the Battalion of Puerto Rican Volunteers, which was formed shortly after the U.S. seized control of the archipelago during the Spanish-American War. Puerto Rican soldiers bolstered the U.S. military’s presence as the new occupying force in Puerto Rico, and later as a segregated division of the regular U.S. Army. In 1917, just a month before the start of World War I, Puerto Ricans were given U.S. citizenship, and several thousand served.

The 65th was designated in 1920; its nickname, adopted during the Korean War, stems from Borikén, the Indigenous Taíno name for Puerto Rico.

Over the years, Puerto Ricans continued to join the U.S. military, ultimately accounting for one of the largest numbers of enlisted service members, with more than 115,000 veterans. The military continues to attract Puerto Ricans seeking a way out of poverty. More than 1,225 Puerto Ricans have died in wars led by the U.S., according to U.S. Department of Defense data.

My grandfather’s connection to the Borinqueneers was evident from the Combat Infantry Badge he wore on his veteran baseball cap.

“If it has the rifle, he was part of it,” Labarca explains. That badge of steel and blue enamel and a dark blue cap is among the documents and photos of his past as a soldier. The family never discussed that part of his life, and he would only wear the badge-adorned cap when he went to his medical appointments at the Puerto Rico Veterans Affairs Medical Center in San Juan.

There was such a disconnect that until recently, I did not realize our family’s linkage to an enormous monument in San Juan, a stone column topped with a metal statue of a soldier. My mom would drive past it every morning on our way to school. As it turns out, this statue pays tribute to my abuelo’s 65th Infantry Regiment.

I knew abuelo had been to the Korean War. I remember my mom saying that he could not watch war movies because they would bring him nightmares “about Korea.” But never had I heard that his participation in that conflict was as part of a famous unit whose name can be seen on several of the main roads across Puerto Rico: la 65 de Infantería. Every time I heard about the Borinqueneers—such as when President Barack Obama awarded members of the 65th with the Congressional Gold Medal in 2014—it did not connect me to my grandfather. The medal “recognizes the contributions and extraordinary heroism of the men of the regiment, who served during a time of segregated units.”

In my family, as with others in Puerto Rico who have relatives serving in the military, there is no reminiscing about the battles nor lingering notions of duty. Military service comes with an emotional, deep-seated conflict: fighting on behalf of the United States while also seeking independence from it.

Abuelo's journey

Abuelo Luis, who died in 2010, was a Puerto Rican Nationalist and pro-independence activist who rarely missed a protest or rally for social justice. One of my most vivid memories, before Alzheimer’s took away his ability to move around freely, was of him marching on a highway as part of a movement demanding the shutdown of the U.S. Navy training grounds on the island of Vieques. (The Navy left Vieques in 2003.)

An avid reader who garlanded me with books and magazines, my grandpa lived a frugal lifestyle.

My aunt Lucy Sánchez González, the eldest of three children, remembers abuelo’s return home following his honorable discharge. The family then moved from Cayey to Savanna, Illinois, where he got a civil servant job at a military base. Looking for better pay, they moved again, this time to Chicago, where he held two jobs at factories, working night shifts that would keep him away until early morning.

“He always told us that the Army was for him un trabajo obligado (a job of necessity),” Aunt Lucy says, “that if he had had the economic means, he would have not enlisted. But he also always said that once you accept a job, you have to be responsible, and you have to do it the best way you can.”