Remembering two icons in the search for Amelia Earhart

Josephine Akiyama claimed she witnessed Earhart’s capture by the Japanese. Elgen Long said he proved she crashed into the sea.

“This lady was a very famous woman, right? I didn’t even know her name. How could I tell a lie?” demanded Josephine Blanco Akiyama over Zoom last summer. She was talking about Amelia Earhart, and Akiyama’s claim that in 1937 she saw a white woman matching the aviator’s description captured by Japanese soldiers on Saipan.

Elgen Long’s version of Earhart’s fate was very different. He said he could prove that Earhart and navigator Fred Noonan crashed into the ocean. “She was in the middle of her last radio message when they went in,” he said in a 2020 interview. “I can tie that down pretty good.”

Akiyama and Long were two of the most influential figures in the decades-long search for Amelia Earhart. Akiyama’s childhood memory set the stage for a proliferation of theories about Japanese skullduggery, aviator espionage, and a government cover up. Long argued that his decades-long research revealed that human errors, by Earhart and others, doomed the flight. They both died last month—Akiyama in Foster City, California, on January 8 at age 95, and Long in Reno, Nevada, on January 26 at age 94. But their theories live on.

A failed mission and undying mystery

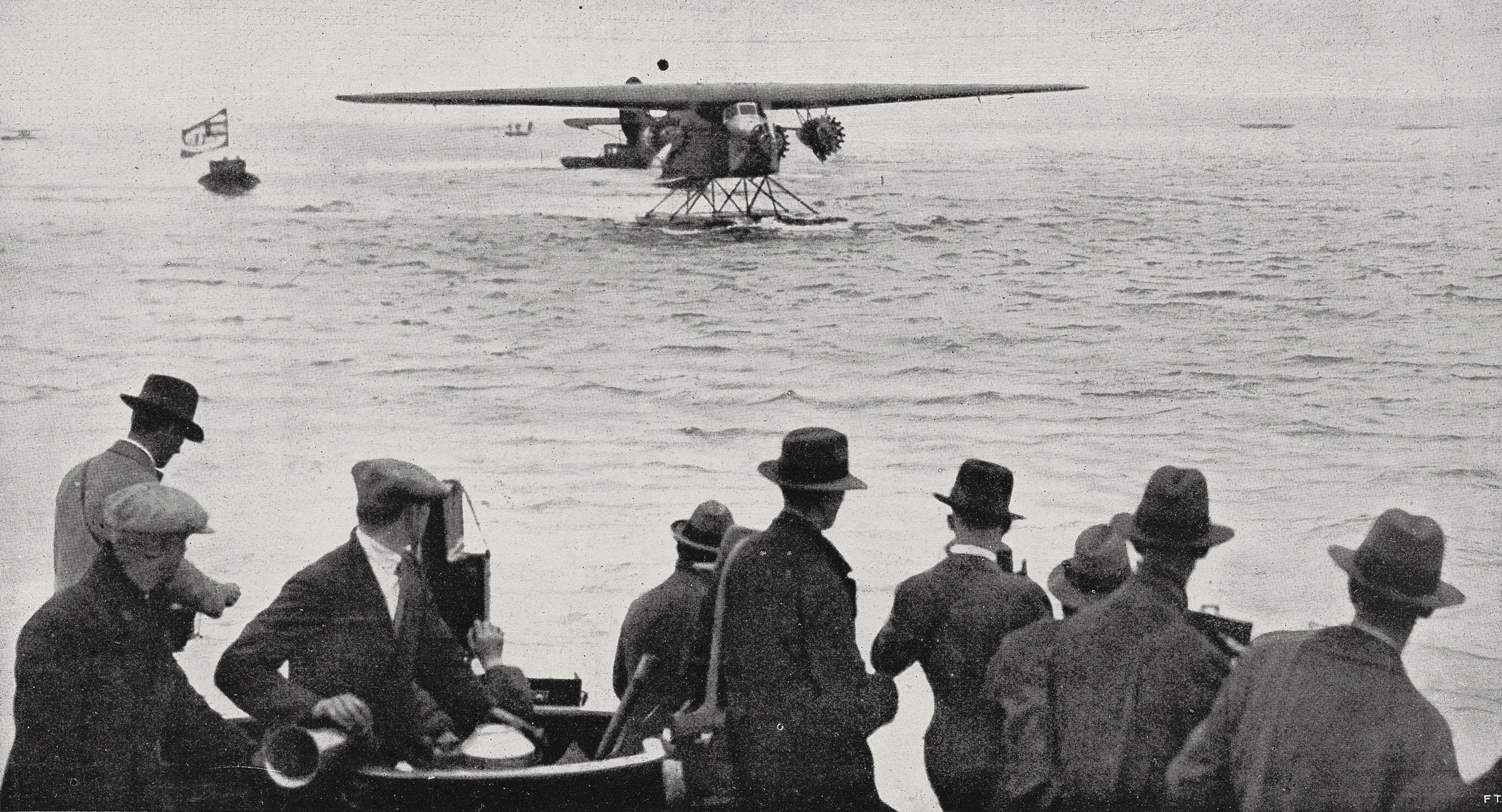

In 1937, Amelia Earhart was attempting to make the first round-the-world flight following the equator. Noonan, who had pioneered Pan American’s commercial routes across the Pacific, signed on as her navigator. On July 2, they took off from Lae, New Guinea, for the third to last leg of the circumnavigation.

They were aiming for Howland Island, a U.S.-claimed speck less than two miles long and more than 2,500 miles away from Lae. But they never arrived. In Earhart’s last message to the Itasca, the Coast Guard cutter waiting offshore to guide them in, her voice was noticeably tense: “Wait. Listening on 6210 [kilocycles],” she said. “We are running north and south.”

The fate of Earhart and Noonan and their Lockheed Electra 10E has been the subject of rampant speculation ever since. The theories loosely fall into three categories: The fliers crashed into the ocean and sank, they were captured by the Japanese and died in custody, or they perished as castaways on an uninhabited island—a theory promulgated by the International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR) and most recently pursued by Robert Ballard, a National Geographic Explorer at Large and the man who found the Titanic.

(Go inside Robert Ballard’s search for Amelia Earhart’s airplane.)

Akiyama was the original source of the captured-by-the-Japanese theory, although rumors had spread among U.S. troops during World War II that signs of Earhart had been discovered on various islands around the Pacific. Born in 1926, Akiyama grew up on Saipan, some 1,500 miles north of Lae. At the time, the island was overseen by the Japanese as part of their South Seas Mandate.

One summer day when Akiyama was 11, her sister asked her to deliver lunch to her brother-in-law at the Japanese seaplane base where he worked. When she arrived there on her bicycle, she saw a crowd gathered around two white men, who seemed to be trying to make themselves understood. But when she overheard Japanese guards speaking nearby, she realized one of the men was actually a short-haired woman wearing pants. “I’d never seen a woman in that kind of clothes,” Akiyama said.

She hid behind a tree to watch. “I didn’t want to get away,” she said. “I just wanted to look and look.”

When she went home and told her mother what she saw, her mother ordered her not to tell anyone. She didn’t want her daughter to get into trouble.

For a long time, Akiyama followed her mother’s instruction. She kept quiet as World War II began and the Japanese confiscated her family’s home. She kept quiet through the Battle of Saipan, in which Japanese and U.S. troops laid waste to the island, killing some 50,000 people, nearly half of them civilians. She kept quiet as the U.S. took control of the island.

She kept quiet until she took a job as an assistant to a Navy dentist named Casimir Sheft. One day the office conversation turned to Amelia Earhart. Akiyama, now 20, had never heard of the aviator, nor did she know the English word for pilot, but when Sheft asked her if she’d ever seen a woman pilot, she said yes.

She had no idea what an explosive story this would become. “If I knew,” she later said, “I would never have said that.”

It’s hard to know exactly what Akiyama told Sheft, as their accounts of the conversation differ—and it was a very long time ago. What’s clear is that the story kept evolving. Sheft shared it with Paul Briand, who published a biography of Earhart in 1960 that concluded with a version of the story attributed to Akiyama that had Earhart’s plane crashing in Saipan and Earhart and Noonan being led away to a firing squad.

A few months after that book was published, the San Mateo Times reported on its front page “San Matean Says Japanese Executed Amelia Earhart.” Akiyama, who had moved to the California town in 1955, said she’d never said that. Her son Ed remembers that she was overwhelmed with strangers calling and coming to the house because the paper had printed their address. Her relatives in Saipan heard that her name was in U.S. newspapers and assumed something terrible had happened to her.

The story had spun out of control. Fred Goerner, a CBS radio reporter, traveled to Saipan multiple times and discovered other people who also claimed to have seen a white woman. But their stories conflicted, especially when it came to how Earhart and Noonan had died, and all the material evidence—a ring, a briefcase, a diary—had somehow disappeared. Goerner suggested Earhart had been on a failed mission for the U.S. government, which then orchestrated a cover up. Others went further, claiming that Earhart had been spirited off the island to New Jersey, where she lived under an assumed identity.

Akiyama didn’t care about any of that. She just wanted to be treated fairly. She kept giving interviews about what she saw, but “she always felt taken advantage of,” says her son.

Cascade of errors

Elgen Long’s relationship with the Amelia Earhart story was far more intentional. Long had served as a radioman on Navy planes in the Pacific during World War II and flew patrols over Howland Island many times. “I never could figure out why [Earhart and Noonan] didn’t find it,” he said.

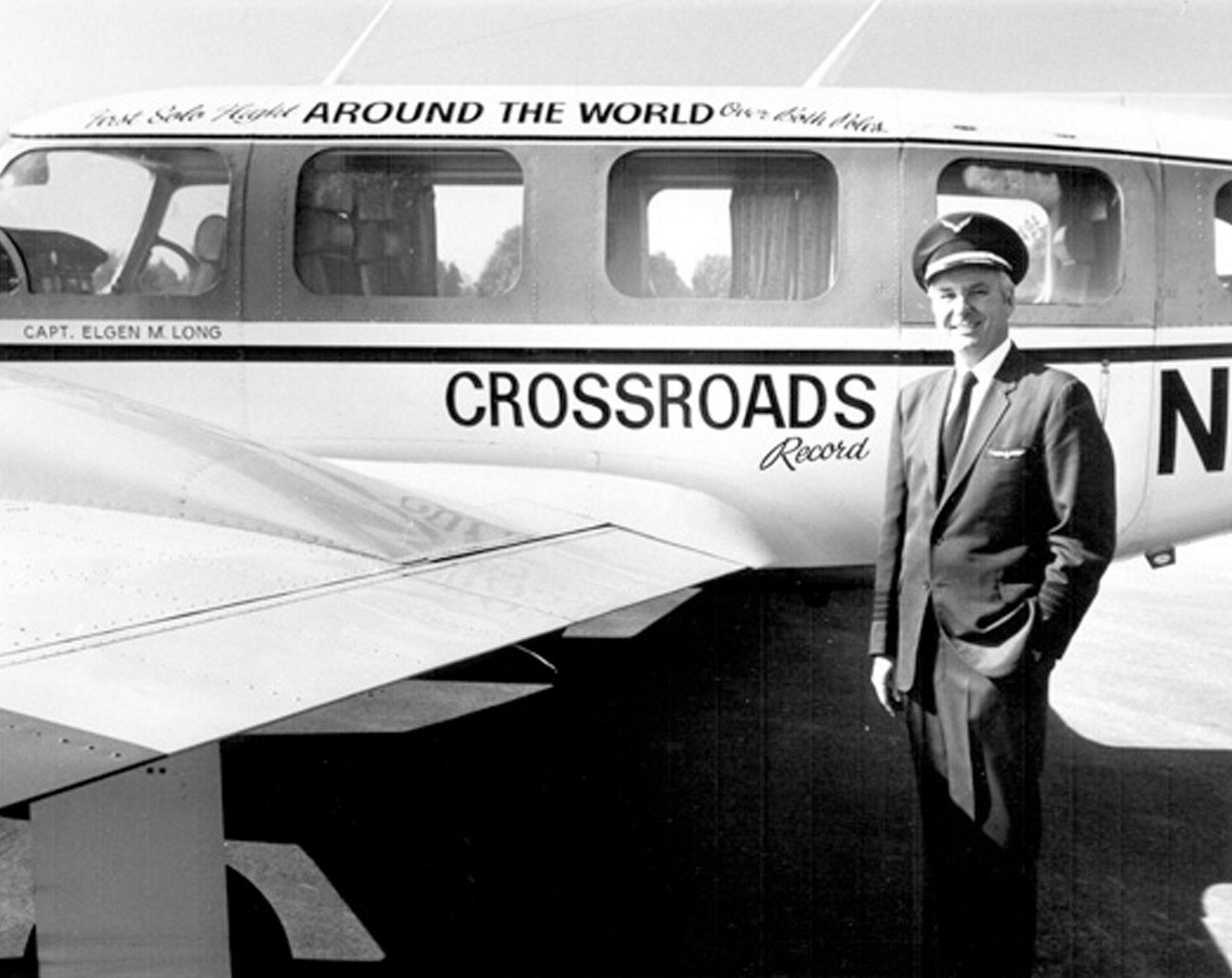

After the war, Long joined the Flying Tiger cargo line, working his way up to navigator and eventually pilot. He did a lot of flying in the northern polar regions, which gave him the idea to circumnavigate the globe at the poles. No one had made that flight alone before. He began to read up on Earhart to figure out how she paid for her record-breaking flights, quickly realizing that neither he or his wife Marie had the fundraising capabilities or public relations brilliance of Earhart’s husband George Palmer Putnam.

Nevertheless, Long successfully accomplished the feat in 1971, breaking multiple records and eager for a new project. He and Marie decided they would figure out what happened to Earhart—using his expert knowledge as a radioman, navigator, pilot, and circumnavigator.

They interviewed everyone involved with Earhart’s flight—from the people who designed the plane’s radio direction finder to the guy who gassed up the plane in New Guinea to the radiomen who tried to contact her from the Itasca. They tracked down every document they could find, including the Itasca’s radio logs and Noonan’s navigational charts from the first half of the flight.

It took the Longs more than 25 years to publish their conclusion: After a cascade of errors, the Lockheed Electra 10E ran out of fuel and crashed into the ocean north of Howland.

In the Longs’ accounting (Marie died in 2003), nearly everyone involved in the flight made mistakes or had the wrong information. Noonan didn’t realize that his charts were out of date, placing Howland six miles to the west of the island’s actual position. He also assumed that his compass didn’t have any deviation, when in fact it was off the mark by nearly four degrees.

The Itasca radiomen thought Earhart and Noonan knew Morse code (they didn’t) and were operating on the same hourly schedule (they weren’t), which thwarted attempts at communication.

The Electra’s radio couldn’t transmit at the low frequency the ship needed for radio direction finding, while a radio direction finder on Howland ran out of battery power before they even neared the island. Earhart had barely learned how to use her own direction finder, which was also labeled with misleading frequency bands.

Meanwhile, the Electra had less fuel than expected because tropical heat had expanded the fuel’s volume in the Lae storage tanks.

None of these errors were insurmountable individually, but together they added up to disaster, Long argued. And their impact on the Electra’s course could be plotted, revealing where to look for the plane’s wreckage. Yet two expeditions by the ocean-exploration company Nauticos based on Long’s calculations turned up nothing.

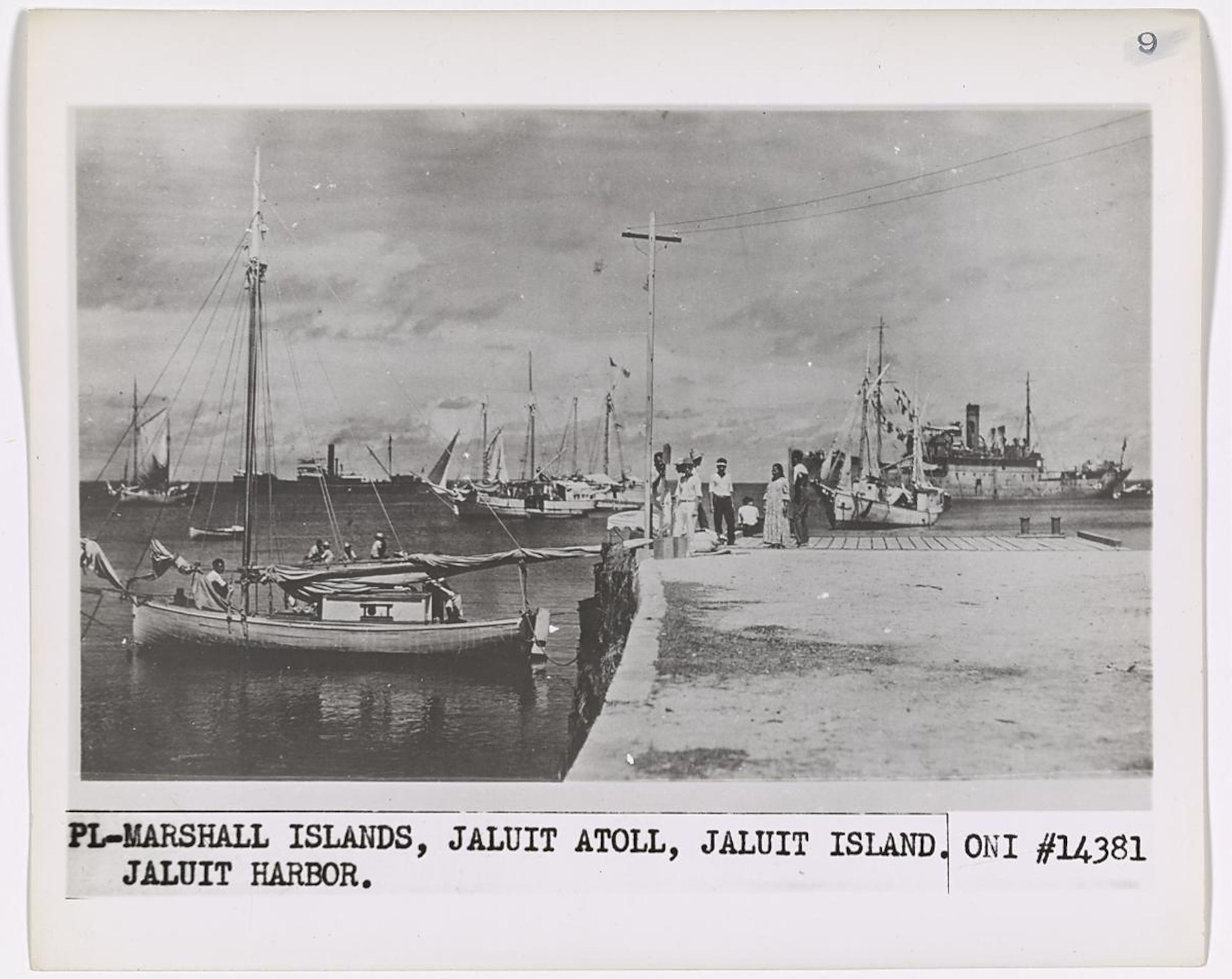

Still, the theories about what happened to Amelia Earhart live on. In 2017, Akiyama’s story was highlighted in a History Channel documentary featuring a photo allegedly of Earhart and Noonan on Jaluit Atoll in the Marshall Islands. (Later evidence shows the image was probably published two years before their disappearance.)

In 2019, Robert Ballard led an expedition to Nikumaroro Island, some 400 miles south of Howland, where members of TIGHAR say they’ve found evidence of a castaway. Ballard and his team on the E/V Nautilus scrutinized the ocean floor around the coral atoll for plane wreckage but came away empty handed.

And in 2020, the team at Nauticos conducted radio signal tests that indicated to them that Earhart had been nearly within visual range of Howland, narrowing where they might look next.

The search continues.