An art curator explains the resonance between the U.S. Capitol’s masterpieces and the riots

In the presence of a mob, the paintings and statues in the U.S. Capitol revealed the complexities of power and politics, an American art curator explains.

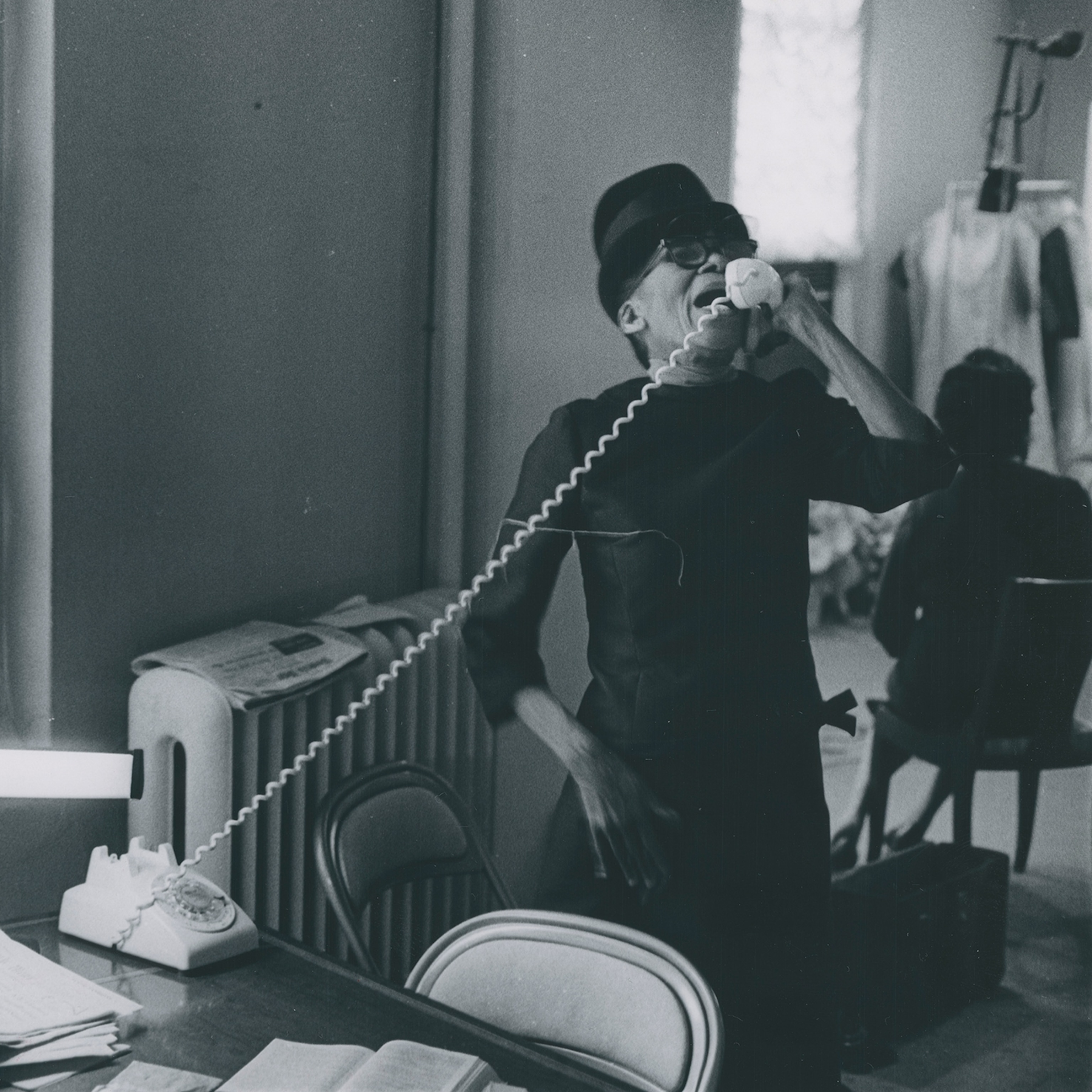

If a picture is worth a thousand words, what can be said in as many about the perplexing and unexpectedly redolent image below? Snapped on January 6, 2021 by Reuters photographer Mike Theiler as rioters invaded the Capitol, it shows a bizarrely fur-clad one among them—later identified as Aaron Mostofsky of Brooklyn, New York—taking a breather from all the breaking and entering going on in the citadel of democracy. (Mostofsky has since been arrested by the FBI on four criminal counts, including felony theft of government property.)

He is in interesting company. Seated outside the Senate Chamber, the insurgent (wearing a bullet-proof vest underneath his animal pelts) pauses beneath the official portrait of Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner by Walter Ingalls. By the time the artist had completed Sumner’s portrait in 1873, the senator had recovered from a brutal caning he endured in 1856 on the floor of the Old Senate Chamber—just beyond where the portrait now hangs—at the hands of fellow Congressman Preston Brooks, a Representative from South Carolina.

Brooks had objected so strenuously to an anti-slavery speech Sumner delivered in May 1856 that he stormed the chamber and mercilessly beat his victim with a gold-headed walking stick. The cane eventually shattered, and Sumner nearly died. Through Sumner’s three years of convalescence, however, the people of Massachusetts held open his seat, leaving his Senate desk empty in silent testimony to the horrific event. (Brooks’s attack was widely praised in southern states, with at least one town and county named after him, and an attempt by northern lawmakers to oust him from Congress failed.)

Ingalls’s painting relates meaningfully to the character below on the couch. The portrait attests to the fact that the Capitol has witnessed great trauma before, and, like Sumner, recovered from it. Outside of this, what coheres these two events—the near-fatal attack on Sumner and the siege on the Capitol—is race. Who can deny that beneath both lie the cry of entitled white men railing against the dilution of their authority by a push for a more diverse, more equitable nation?

In his portrait, Sumner looks appropriately leftward, whereas the other figures in the photo face right, which seems equally fitting in the case of both the man on the bench who was charged in last week’s violence, and that of the man represented in the marble bust nearby—Richard Nixon, whose likeness was commissioned for the Senate gallery of vice presidential busts when he served under Dwight Eisenhower. Twice elected president, Nixon resigned the presidency in 1974 rather than face impeachment for obstruction of justice, abuse of power, and contempt of Congress. Now boxed and cordoned in a tiny niche, the sculpture seems to contain as much as celebrate the man, who like the rioters, evinced an unequivocal disregard for the law.

Another photo taken by Theiler captures a portrait of a pro-slavery congressman and vice president from South Carolina hanging to Sumner’s left. The “ragged, wiry character” (as a New York Times art critic of the day described the 1858 portrait) is John C. Calhoun. The photograph was made just as one of last week’s raiders paraded past Calhoun’s likeness with a Confederate battle flag—a symbol never before brandished in the Capitol. (How the Confederate battle flag has been claimed by white supremacists and mythologized by others as a symbol of southern heritage.)

It is fitting that the rebel flag, adopted in the 20th century across the South as a symbol of opposition to the Civil Rights movement, inclines toward Calhoun, who owned dozens of slaves and was among slavery’s and the South’s most powerful and ardent defenders. His ideology helped lay the groundwork for secession, though he died before the Civil War. Today he remains a hero to many on the far right.

The sandwiching of Sumner’s portrait between likenesses of a racist South Carolinian and a corrupt Californian speaks volumes to the difficulty of doing lasting political good in this large and varied country, just as the identity of the particular alleged rioter in Theiler’s first photo, who turns out to be the son of a Modern Orthodox judge from New York, underscores the complexity of our citizenry and politics—all the more so in light of photographs showing other rioters brandishing anti-Semitic symbols, including a “Camp Auschwitz” sweatshirt worn by Virginian Robert Keith Packer, who has since been arrested.

Then again, Calhoun’s absence from the photo of the fur-clad Mostofsky presages the portrait’s intended removal from the Capitol, along with others depicting Confederate leaders, following legislation approved by the House in July 2020. In light of this, the photos of Confederate flags trailing rioters as they stroll throughout the building are even more jarring. (See a historic day in photos: from a pro-Trump insurrection to a pre-dawn Biden victory sealed.)

One might stray further still beyond these images, down the hall to the Rotunda, to consider other juxtapositions of real and painted people. Among the several large paintings by John Trumbull enshrining American history and ideals is one depicting George Washington renouncing power at the close of the Revolution (above). In so doing, Washington ended widespread speculation he would seek to maintain authority indefinitely, as the latter-day rioters now seem to wish for their very different hero, Donald Trump. To those who desired that he become King of the United States, Washington replied that “no occurrence in the course of the War, has given me more painful sensations.” Such a move, he continued, would constitute one of “the greatest mischiefs that can befall my Country.” (Of course, Washington returned to leadership as president seven years later, but he did so by winning an election.)

In 1796 after serving two terms, President Washington again walked away from power. In his farewell address, he warned of “a small but artful and enterprising minority of the community” whom he thought “likely, in the course of time and things, to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government, destroying afterwards the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion.”

In addition to the familiar thousand-word adage about pictures, another phrase surrounding them is that of the so-called photo finish, referring to a race so tight that a photograph must determine the outcome. The recent presidential election was no such contest, despite the protesters’ protestations. Perhaps images of the calamity in the Capitol will document a more literal kind of photo finish: pictures of the end of an era.