6 of the biggest shipwreck treasures ever found

These historic wrecks offer more than just gold and jewels. From the coast of Namibia to the South China Sea, these ships held riches hidden from time.

Splintered wood pokes out of the sandy bottom of the sea, fish darting in and out of their shadows. Among the rotted planks, the bones of sailors who fought enemies or braved storms rest in the deep, cold silence. Little light reaches this far down—but a trained eye might glimpse a glint of gold or a sparkle of a gem, hidden from time.

Indeed, it’s these treasures that have motivated adventurers to explore the seas in search of fortune.

(In 1989, three tons of gold were found on the 1857 wreck of the SS Central America. Watch the three-part series Cursed Gold: A Shipwreck Scandal premiering August 21 at 8/7c on National Geographic and streams the next day Disney+ and Hulu.)

Nowadays, however, the rules around who can claim these antiquities are far more complicated. There are serious concerns, from archeologists and regional authorities alike, that looters could destroy the delicate structure of an old, decayed ship. Looters might also sell those artifacts to a private owner, robbing the public of the opportunity to learn their history and see them on display.

That’s why archeologists and maritime law enforcement are trying to preserve these fragile pieces of cultural heritage.

Regardless of who owns the wreckage, troves of valuables discovered on shipwrecks have set records with valuations in the billions and inspired imaginations around the world.

These are a few of the biggest shipwreck treasures ever discovered—both examples of why their ownership is so contested and testaments to why these underwater ruins should be protected.

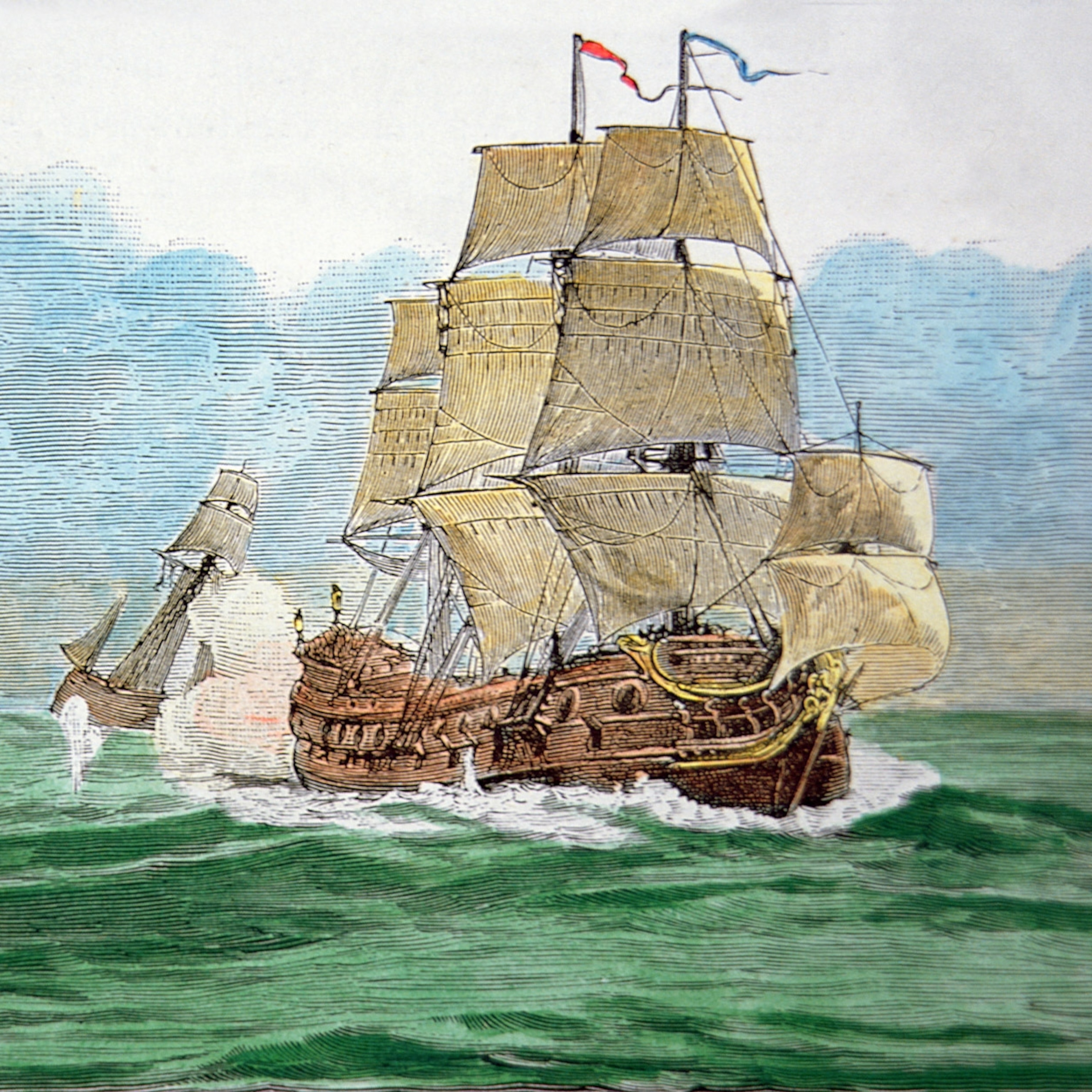

The San José in the Caribbean Sea off the coast of Colombia

Often called “the world’s richest” shipwreck, Spanish naval galleon San José carried up to 200 tons of gold, silver, and uncut gemstones when it sank in 1708 during a battle with British warships.

Estimates of the ship’s treasure range from a few billion dollars to more than $20 billion. A number of parties have argued their right to claim the wreck, including a U.S.-based salvage company (who claimed to have found the wreck in 1982), Colombia (who said they found the wreck at a different location in 2015), Spain (which argues they still own the ship as they did 300 years earlier) and a group of indigenous Bolivians, who say their ancestors were forced to mine much of the silver.

Regardless of the treasure’s true value, Colombian law dictates all artifacts cannot be sold. The San José and its treasures are still at the bottom of the sea, and some archeologists believe it would be safest for the artifacts to stay there.

The Bom Jesus on the southern coast of Namibia

In 2008, a geologist was looking for diamonds in an area known for deposits of the gemstone. Instead, he found something else—a copper ingot. Archeologists went on to find 22 tons of these ingots (used to trade for spices at the time), as well as more than 100 elephant tusks, a bronze cannon, swords, astrolabes, muskets, and chainmail—thousands of artifacts in all.

(Read more about the Bom Jesus or “Diamond Wreck.”)

And they found gold—more than 2,000 coins, mainly Spanish and bearing likenesses of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, but also some Venetian, Moorish, French and other coinage.

This cargo helped identify the ship as the Bom Jesus, a Portuguese trading vessel lost in 1533 while headed to India. The ship and all its cargo laid untouched for nearly 500 years. It is by far the oldest shipwreck ever found on the coast of sub-Saharan Africa and the richest.

The Belitung Shipwreck in the Java Sea off Belitung Island, Indonesia

In 1998, local fishermen diving for sea cucumber discovered a block of coral with ceramics embedded in it. The find ultimately turned out to be a ninth century Arab dhow filled with more than 60,000 handmade pieces of Tang dynasty gold, silver, and ceramics.

(Read more about the Belitung Wreck.)

The ceramics, in particular, were a snapshot of the Changsha ceramics industry, the Tang dynasty, and silk road trade at large. China at the time was eager to buy fine textiles, pearls, coral, and aromatic woods from Persia, East Africa, and India. By the ninth century, ceramics from China had grown popular, but camels weren’t suitable to carry the fragile product. So, increasing quantities of the dishes and plates arrived by sea via the “Maritime Silk Route.”

Although Arab mariners clearly used the Maritime Silk Route, "this is the first Arab dhow discovered in Southeast Asian waters," John Guy, senior curator of South and Southeast Asian Art at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, told National Geographic for our 2009 report. The wreck is also "the richest and largest consignment of early ninth-century southern Chinese gold and ceramics ever discovered in a single hoard."

Palmwood Wreck in Wadden Sea off Netherlands

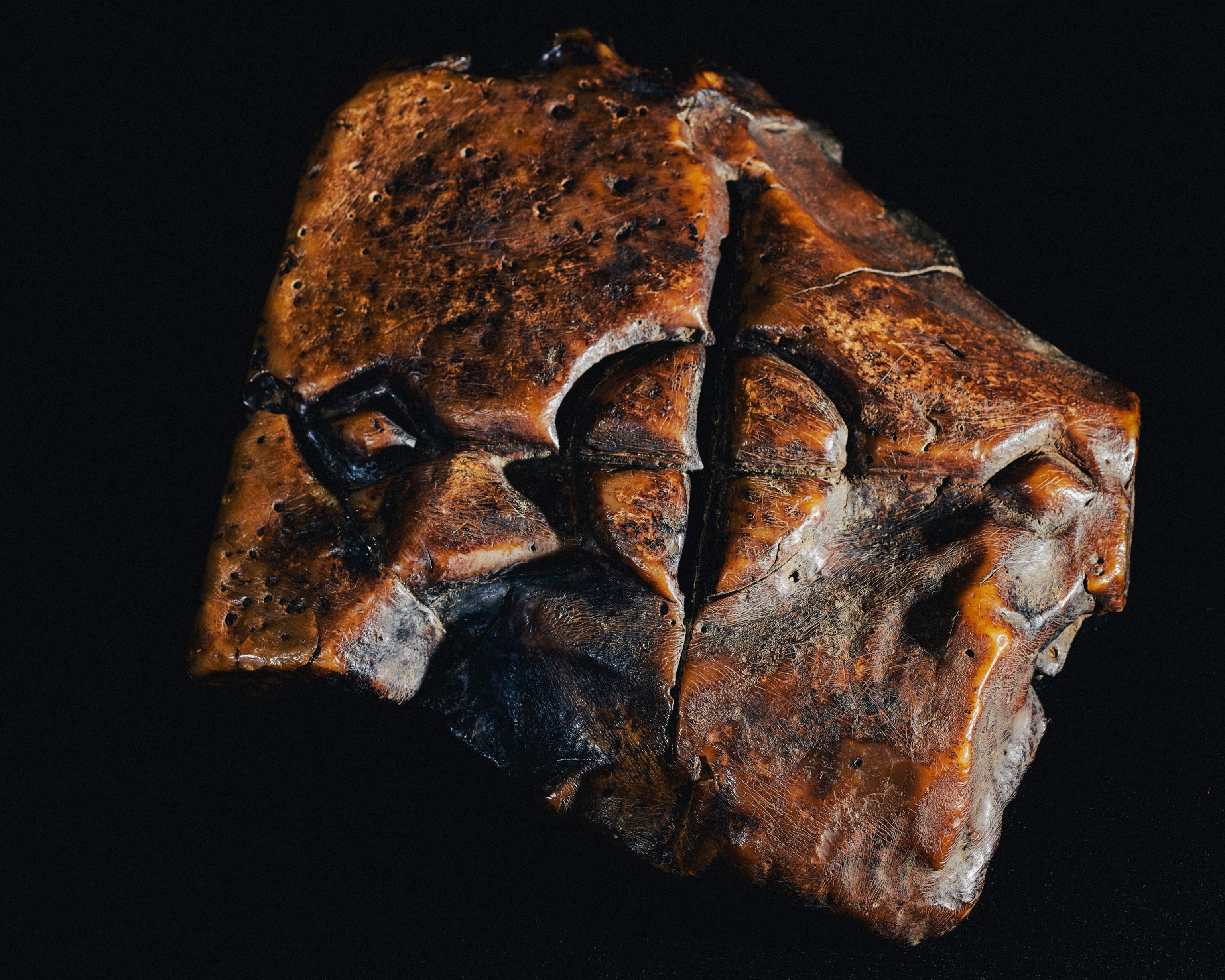

Named for the hardwood boxes that held the ship’s pricey cargo, the Palmwood Wreck contained riches from around the world and insights into the life of 17th century elites.

Within these broken boxes, divers brought up over 1,500 artifacts including an elegant dress embroidered with silver love knots, an elaborate damask gown, and a velvet tunic dyed with cochineal, a ruby-hued pigment obtained from insects only found in the Americas. Researchers also found a silver cup and tableware, luxury toiletry set, Persian carpet, and an international collection of 32 leather-bound books dating to the 16th- and 17th centuries.

(Read more about the Palmwood Wreck.)

While conservators have their hands full with the items that have been recovered from the seabed so far, most of the Palmwood Wreck remains unexcavated, swathed in a mesh protective cover to shield it from destructive currents.

The Nanhai No. 1 in the South China Sea off Yangjiang, China

In 1987, while looking for a Dutch East India Company ship that sank in the 1700s, British company Maritime Exploration instead found an intact 100-foot-long merchant vessel from the 1100s.

(Read more about the Nanhai No. 1)

A six-foot-thick layer of silt had preserved its wooden hull and cargo, including porcelain, Song-era coins, and bars of silver. Over the years, archaeologists have recovered tens of thousands of objects from the Nanhai No. 1, including 100 gold artifacts and thousands of coins. Most of the 60,000 to 80,000 objects on the Nanhai No. 1, however, are ceramics from the Southern Song.

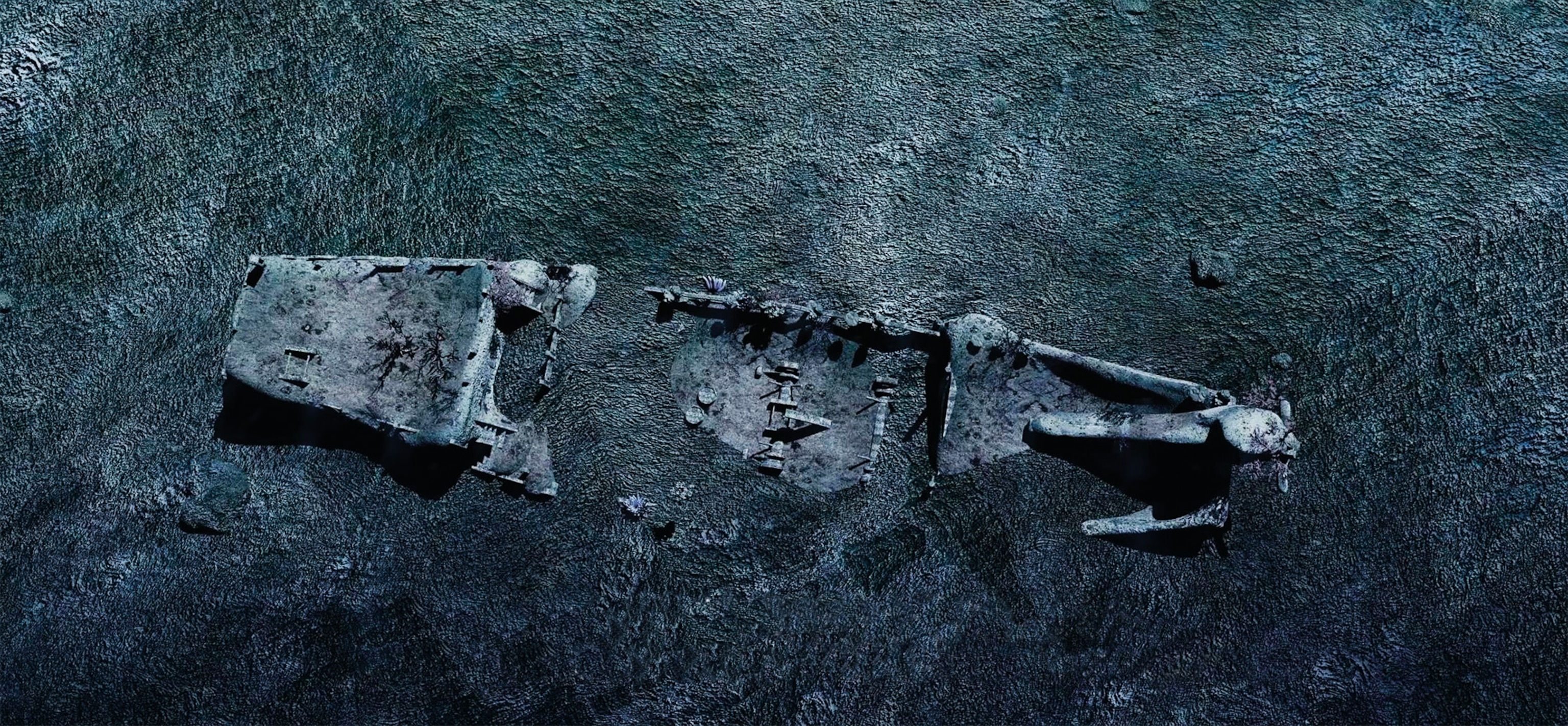

Santo Cristo de Burgos in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Oregon, USA

The Spanish galleon was sailing from the Philippines to Mexico in 1693 when it veered off course and vanished, most likely wrecking on what’s now Oregon’s coast. About a dozen timbers have been find from a ship hull that was active around the time the Santo Cristo disappeared, making them likely artifacts. Its cargo included costly Chinese silk and porcelain.

(Learn more about the Santo Cristo de Burgos.)

Blocks of beeswax imported from Europe also washed ashore in the centuries after the ship sank. Small bits of blue-and-white porcelain as well as large pieces of wood also hinted a wreck was nearby, stoking legends of treasure among local Native people.

By the late 19th century, local legends of treasure and galleons—and the hunt for them—regularly appeared in the pages of Oregon newspapers. Those reports caught the attention of filmmaker Steven Spielberg and likely inspired his idea for the 1985 film The Goonies, though he has never confirmed the connection.