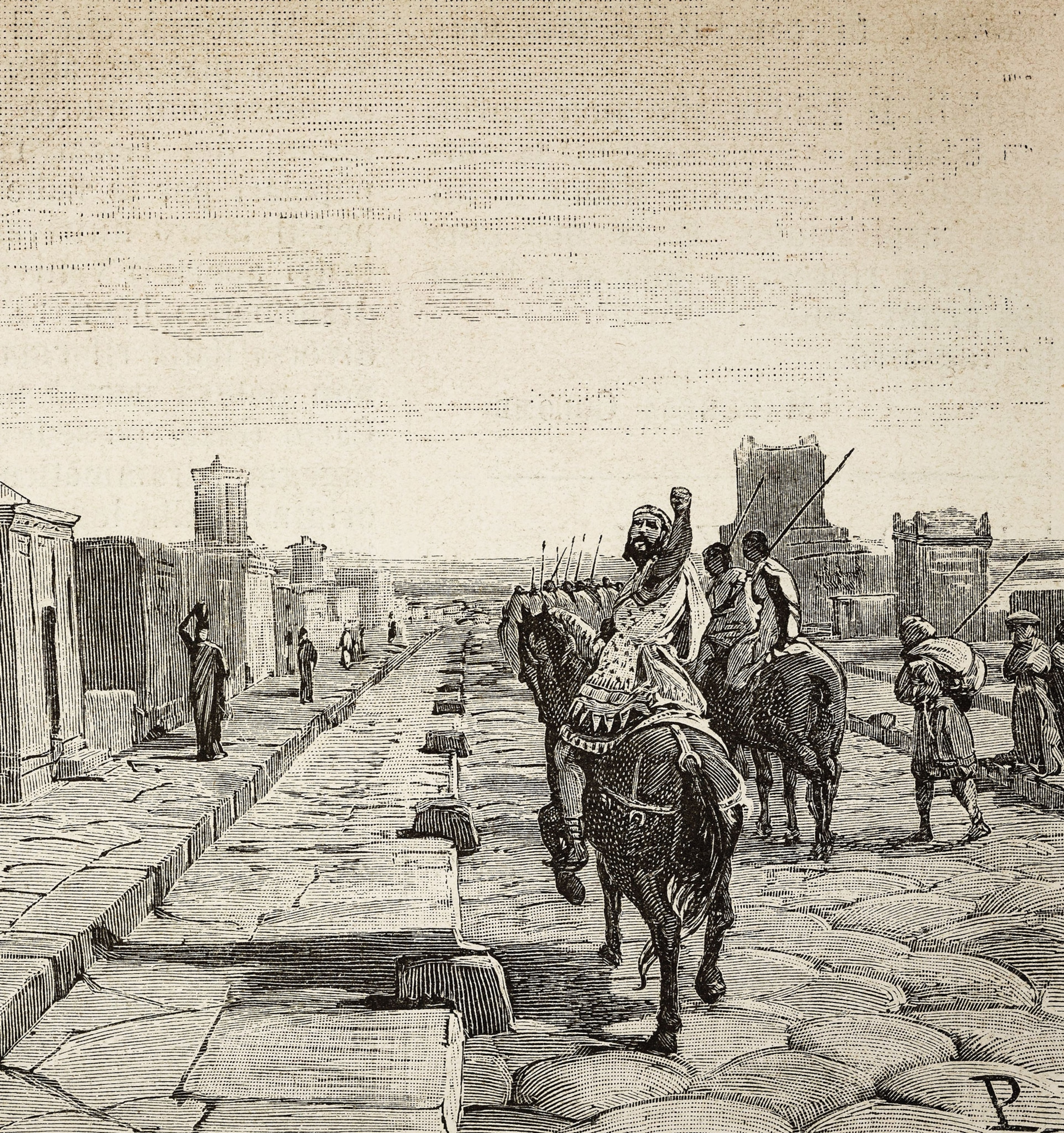

This ruthless African king knew Rome was for sale. He bought it

Jugurtha, king of Numidia, murdered rivals and bribed Roman officials to look the other way, sparking a war and exposing the republic's corruption.

Struggling to subdue the people of Spain in 134 B.C., Roman general Scipio Aemilianus realized he needed more troops. He turned to Numidia, a North African ally whose ruler, Micipsa, was glad to provide Numidian soldiers. A loyal ally of Rome in its recent victory over Carthage, Numidia (located in parts of modern Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya) had an underlying motive for helping Rome: Micipsa could send his nephew Jugurtha to command Numidia’s forces.

Charismatic, clever, and aggressive, Jugurtha represented a threat to Micipsa’s throne and his two sons. Assisting Rome in Spain would conveniently put Jugurtha in harm’s way. Perhaps he would never return.

But Jugurtha did return after a decisive Roman victory at Numantia with a glowing letter of recommendation from Scipio. His military and political reputation enhanced, Jugurtha had also established valuable Roman connections. To diminish his threat to the throne, King Micipsa decided to adopt his nephew and include him in a three-way split of the kingdom with his biological sons, Hiempsal and Adherbal. Jugurtha’s ambition was undeniable, and he would not be content to co-rule with his adoptive brothers.

Most of what is known about Jugurtha’s life comes from two Roman historians: Sallust and Plutarch, who recorded how he employed bribery, treachery, and murder in ruthless pursuit of sole control of Numidia. The civil conflict, the Jugurthine War, would turn into a costly distraction for Rome that exposed the corruption eating away at the heart of the Roman Republic.

Numidian Kings

The kingdom that Jugurtha strove to rule alone arose during the Second Punic War fought between Rome and Carthage in the third century B.C. Allying himself with Rome, Jugurtha’s grandfather, King Masinissa, united the region under his rule as the kingdom of Numidia. His land prospered, and following Rome’s destruction of Carthage in 146 B.C., Masinissa’s son, Micipsa, continued ruling as a Roman ally. His division of the kingdom into three provoked the Jugurthine War. The kingdom made the wrong call during the Roman civil wars in the first century B.C. when King Juba I sided against Julius Caesar. Following Caesar’s victory and rise to power, Numidian independence ended.

Family affairs

After the death of Micipsa, Jugurtha immediately contested the division of power. Gathering his soldiers, he sent them to Hiempsal’s quarters where they ransacked the house, killed anyone who resisted, and discovered Hiempsal hiding in the cell of a maidservant. As ordered by Jugurtha, they cut off Hiempsal’s head.

Adherbal fled to Rome, where he declared to the Senate that Jugurtha was a traitor and had murdered his own brother. He demanded punishment, and the Senate set up a commission to investigate. Quoted in Sallust’s first-century B.C. work, Jugurtha describes Rome as “urbem venalem et mature perituram, si emptorem invenerit—a city for sale and doomed to speedy destruction if it finds a purchaser”—a valuable lesson he learned during his time with Roman troops in Spain. To fight his adoptive brother’s accusations, Jugurtha applied this lesson and bribed his friends in the Senate. The commission decided to split Numidia between Jugurtha and Adherbal, each man in charge of his own section. Jugurtha’s role in the assassination of Hiempsal was overlooked. (Meet Crassus, the richest man in ancient Rome.)

[B]eing ordered by the senate to leave Italy. After going out of the gates, it is said that [Jugurtha] looked back at Rome in silence and finally said, 'A city for sale and doomed to speedy destruction if it finds a purchaser!'Sullust, The War With Jugurtha

Encouraged, Jugurtha turned to building up his forces at home and then securing the throne for himself. He attacked Adherbal and pushed his forces back. Adherbal retreated, secured himself in Cirta, the capital of his portion of Numidia, and appealed to Rome for help. Jugurtha’s armies besieged the walled city of Cirta, sealing it off from any shipments of food or supplies.

Sallust recorded how Adherbal begged Rome to deliver him from “the inhuman hands” of Jugurtha, but Roman envoys failed to bring Jugurtha to terms. Adherbal surrendered, trusting that the status of the many Romans trapped with him in Cirta would make Jugurtha act mercifully. Undeterred, Jugurtha took the city, tortured Adherbal until he died, and killed the adult occupants of the city, including those of Italian descent.

Money talks

In killing the Roman occupants, Jugurtha crossed a line. Facing a popular outcry, the Senate declared war against him and sent troops to fight the rogue Numidian king in 112 B.C. The decision surprised Jugurtha, Sallust wrote, because “he had a firm conviction that at Rome anything could be bought.” Even so, Jugurtha probably had reason to believe he could win over Rome again because Rome’s existing conflicts with Germanic tribes closer to home made fighting with him in North Africa less of a priority.

Lucius Calpurnius Bestia led Roman forces in North Africa in 111 B.C. Bestia’s campaign began with victories but was undone by bribes. Jugurtha doled out bribes to the invading forces. He warned Bestia that a prolonged war was the last thing Rome wanted. His tactics paid off: When Jugurtha surrendered to Bestia, the terms were very favorable to him.

Despite sparing Rome from war, this arrangement was seen as a great dishonor by the Roman public. Gaius Memmius, tribune of the plebeians (described by Sallust as “a man fiercely hostile to the power of the nobility”), accused the aristocrats in the Senate of accepting Jugurtha’s bribes. (Romans prized these jewels more than diamonds.)

A new commander

Jugurtha was again brought from Numidia to Rome to defend himself against the accusations. During his visit, he bribed officials in a bid to ease his sentencing process. He was promised safe passage home, but before he left, Jugurtha found a royal Numidian cousin, and rival to the throne, living in Rome and had him killed.

The murder of a prince under protection of Rome was a provocation too far. In 110 B.C. war was renewed with more experienced generals, during which Rome’s rivalry between nobles and plebeians intensified. (Discover how Hannibal staged a legendary attack against Rome.)

The consul Quintus Metellus won significant victories over Jugurtha, but was unable to capture him. In 107 B.C. the plebeians wrested the command in Numidia from Metellus and gave it to his subordinate, Gaius Marius. The new commander had just been elected consul partly on the strength of his modest roots and promises to tackle corruption.

Marius was gifted with formidable military skills, and was popular among the troops. Yet even Marius had difficulty capturing Jugurtha, who had persuaded his father-in-law, Bocchus, king of Mauretania, to shelter him.

With great diplomatic and military flair, Jugurtha drew Roman troops into a wearying game of cat and mouse. It was only in 105 B.C. that Rome managed to strike a deal with Bocchus. In return for control of a large portion Numidia, Bocchus handed over his errant son-in- law. Writing in the first-century A.D., Roman historian Plutarch recounts in his “Life of Marius,” in Parallel Lives, that the subdued Jugurtha was paraded in chains through Rome and imprisoned, where he died sometime afterward of starvation.

Jugurthine legacy

Although Rome’s military might crushed Jugurtha, his courage, craftiness, and brilliant guerrilla tactics are a remarkable chapter in the annals of Rome’s military history; Jugurtha’s true motivations in provoking this conflict are unclear in the historical record. Some assume he wanted to free Numidia from Roman influence. Others believe his aim may have been to reinstate himself as an ally of Rome.

The historian Sallust’s account is often cited as the main source for Jugurtha, and Sallust’s background colors his account. A nonaristocrat, Sallust was elected tribune, but his career was cut short by infighting when he backed a rival of Julius Caesar in the civil wars of 49-45 B.C. His subsequent career as a historian was colored by his relatively humble roots and focused on the corruption and arrogance of the aristocratic elite. (Here's how Julius Caesar started a big war by crossing a small stream.)

His preoccupations found a perfect theme in his history of the Jugurthine War, written circa 40 B.C. Historian Gareth C. Sampson, author of The Crisis of Rome: The Jugurthine and Northern Wars and the Rise of Marius, argues that “Sallust had an ax to grind about the decay of Roman elite society, and Jugurtha was a prime example that he could exploit to ‘prove’ his case.”

Jugurtha’s legacy certainly supports Sallust’s interpretation of events. After the Jugurthine War, the plebeian assembly used Jugurtha’s bribes and the Senate’s incompetence to gain power through brilliant soldiers like Marius. The erosion of senatorial power in favor of individual generals would increasingly destabilize the Roman state and lead to the civil war that gave rise to Julius Caesar.