Mysteries of King Tut: What we still don't know

Even a century after his tomb's discovery, questions still linger over the teenage pharaoh's life, loves, successors, and death.

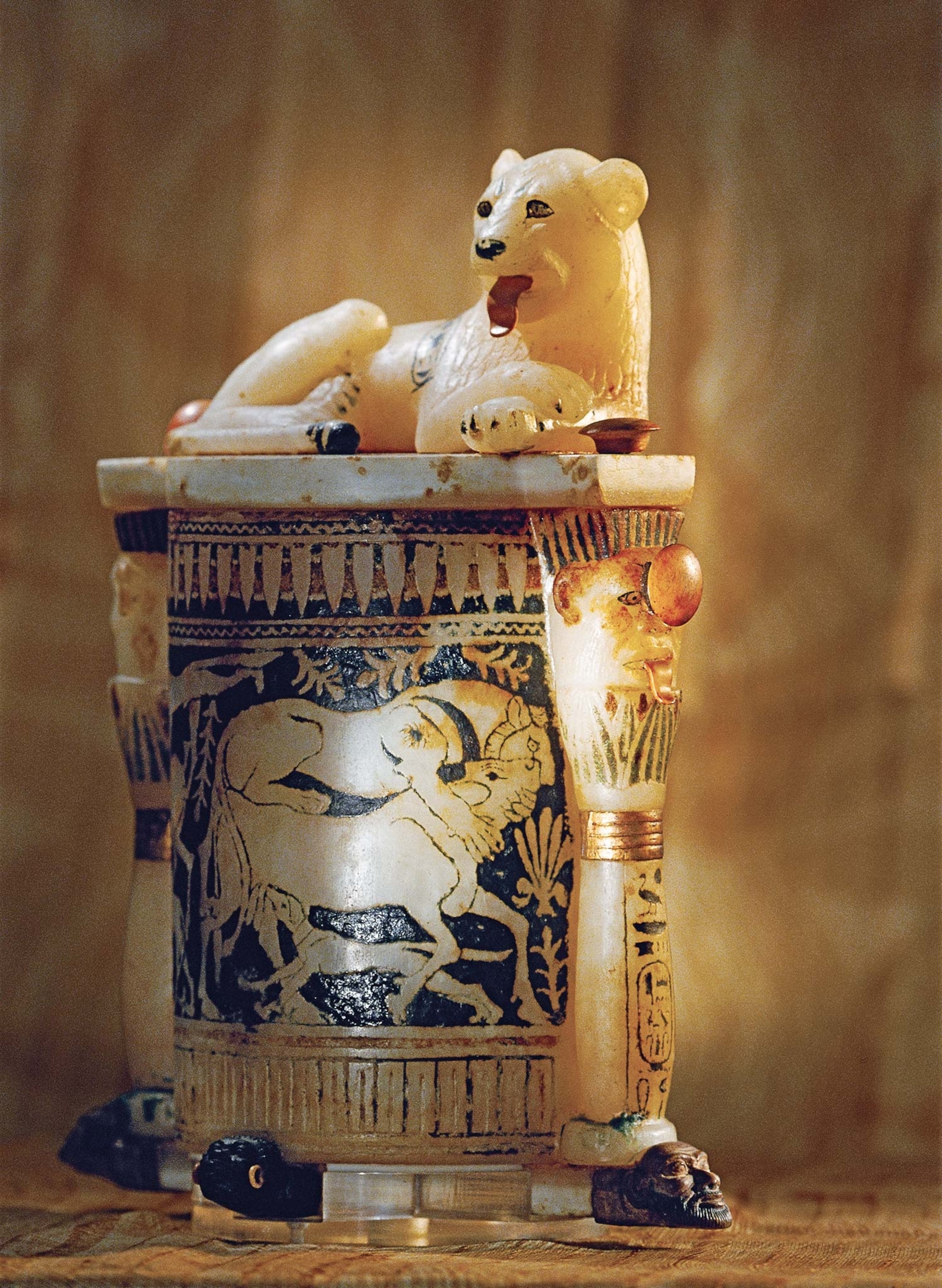

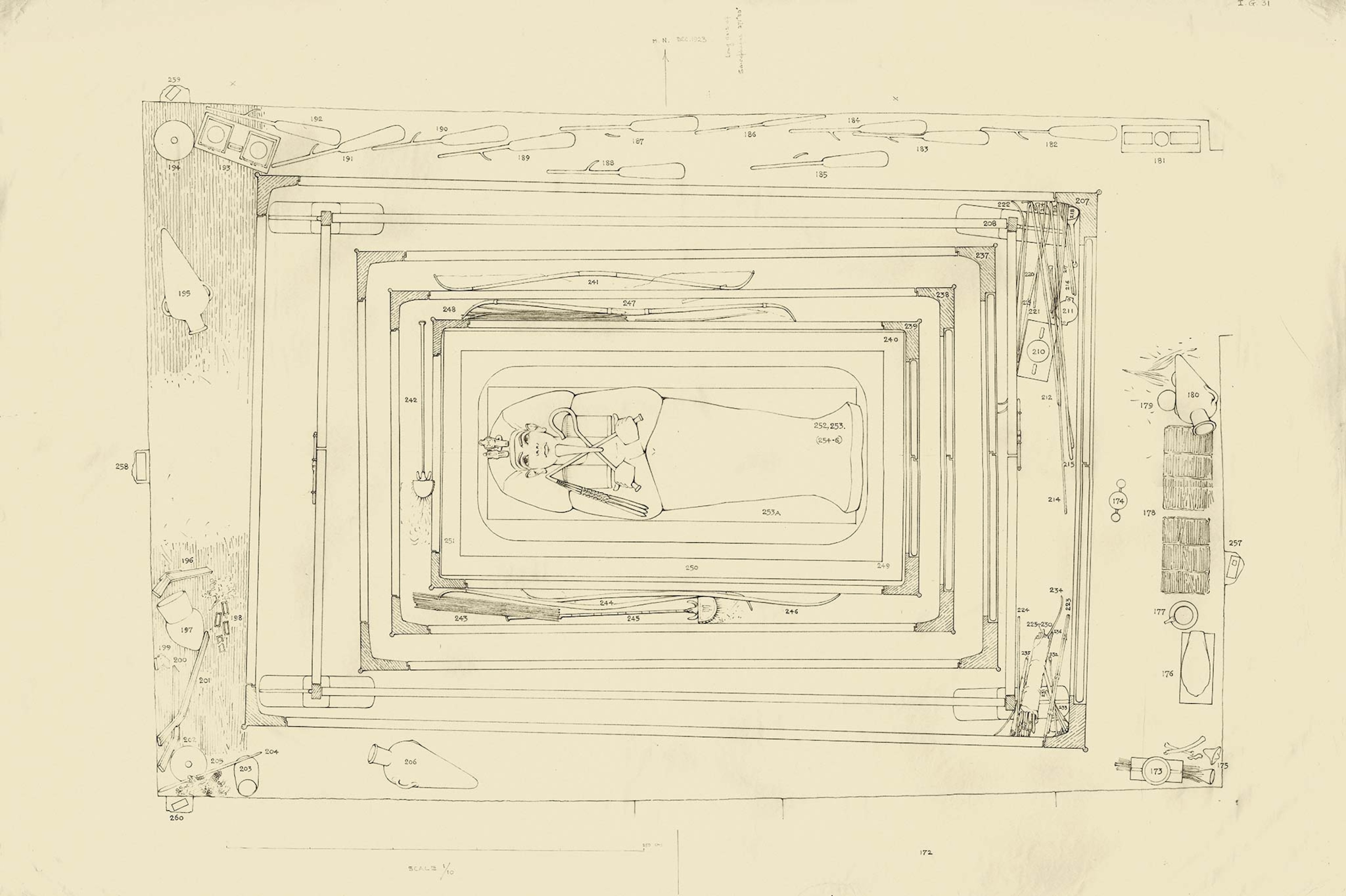

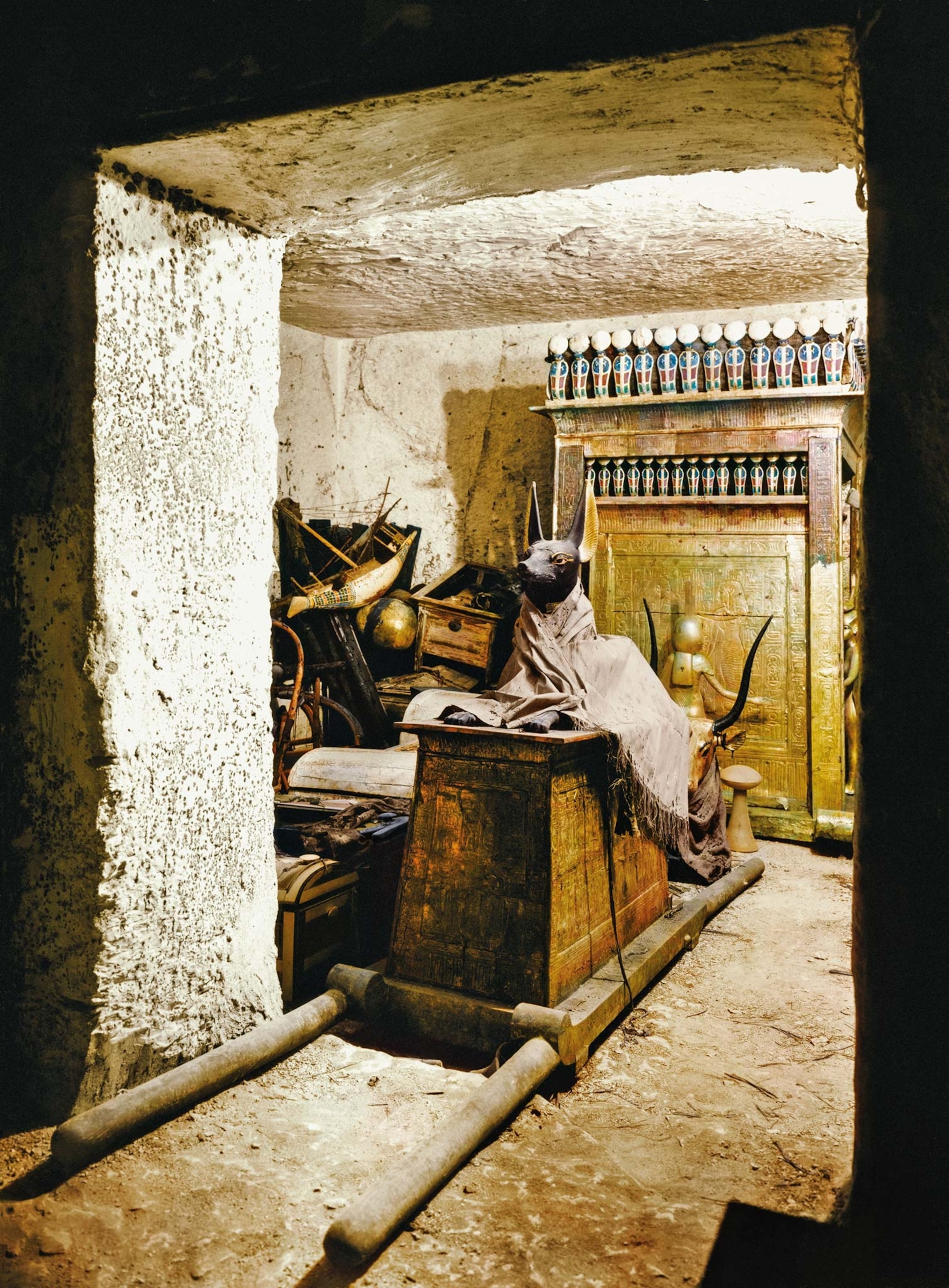

From the earliest days of archaeology in Egypt, the Valley of the Kings has exerted an irresistible allure. The famed cemetery was the burial place of royals during the golden age of the 18th, 19th, and 20th dynasties. Conducted since at least the early 1800s, excavations have revealed that most of the rock-cut tombs in the area were thoroughly looted in antiquity. The one great exception—the four richly appointed chambers of King Tutankhamun Nebkheperure—yielded not only a stunning trove of artifacts but a glimpse of the country’s astounding wealth and culture during the 14th century B.C.

Since its discovery in 1922, King Tut’s tomb has provided ample evidence that has allowed both experts and amateurs to puzzle out the young pharaoh’s life and times, including the political intrigues that must have swirled around him in the wake of his succession to the throne. Some parts of the picture fit neatly together, while other details are not so clear. Now, a century after the tomb’s discovery, is perhaps a fitting moment to consider what the experts have learned, and at what they can still only guess.

Surprising finds

The story of the discovery of King Tut’s final resting place begins in 1902, two decades before its discovery, when Egypt granted permission to American lawyer and businessman Theodore Davis to dig in the Valley of the Kings. Davis would go on to fund excavations there for more than a decade, discovering and excavating some 30 tombs. He also unearthed tantalizing clues about the young king, whose name was mostly absent from historical records.

(10 things to know about the discovery of King Tut's tomb.)

Davis came across two minor deposits containing artifacts with Tutankhamun’s name. One was an embalming cache; the other held embossed, decorative gold from chariots. Davis believed he had found the mysterious pharaoh’s burial, but he was disappointed with the artifacts. Other underwhelming discoveries that he made subsequently convinced him that it was finally time to quit.“I fear that the Valley of the Tombs is now exhausted,” he explained.

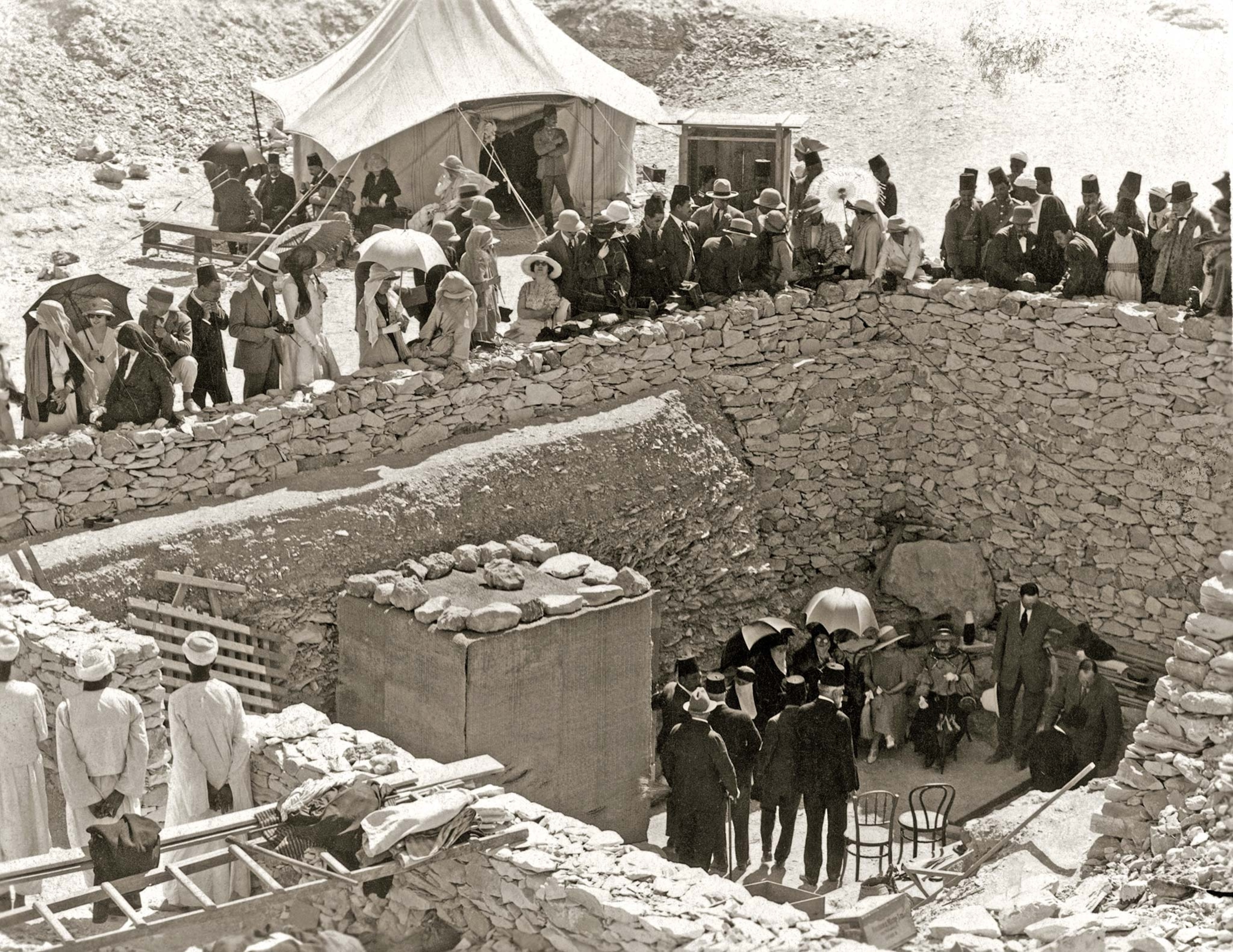

According to one report, Davis had come within six feet of Tutankhamun’s tomb. His pivotal decision to give up his concession in the valley on the very brink of success allowed Lord Carnarvon, a wealthy Englishman, to step in in 1914. Working for Carnarvon, archaeologist Howard Carter conducted excavations over the next eight years before uncovering the steps leading to King Tut’s tomb on November 4, 1922.

After slowly, carefully removing and cataloguing many hundreds of dazzling funerary artifacts, Carter was finally able to open Tut’s nested coffins in late 1925 and gaze upon the mummy. “The youthful Pharaoh was before us at last: an obscure and ephemeral ruler, ceasing to be the mere shadow of a name,” he wrote. “Here was the climax of our long researches.” By then, King Tut had become one of the most famous people in the world. His image and name were everywhere. In the field of Egyptology, the once little-known ruler was now one of the pharaohs that historians knew best.

(How King Tut conquered pop culture)

Who were Tut's parents?

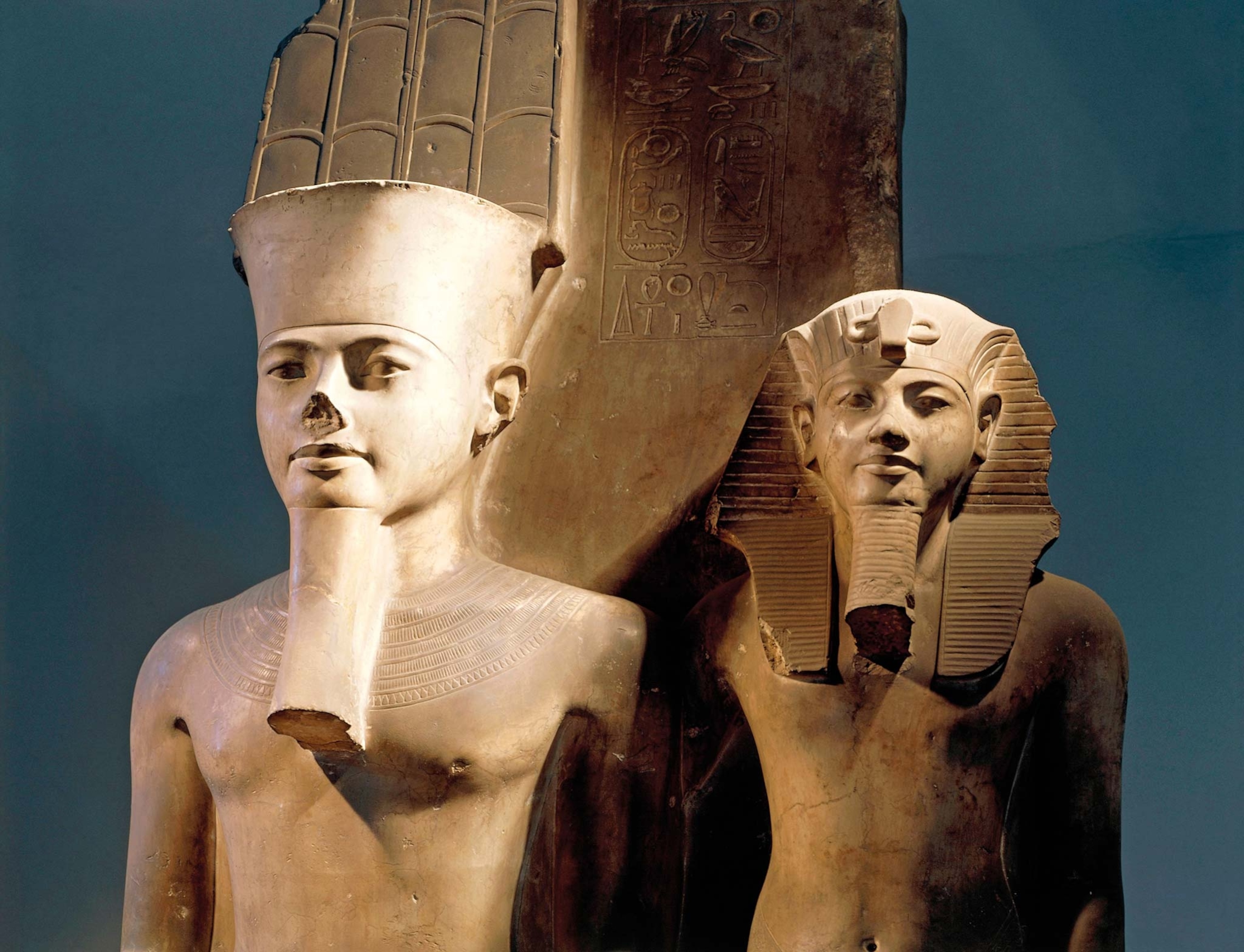

Clues uncovered in Tut’s tomb—KV62, the 62nd burial complex found in the valley —confirm that he was one of the successors of heretic king Amenhotep IV. The latter chose a new name, Akhenaten, meaning “effective for the Aten,” the god that the king decided to worship to the exclusion of all others. In the distinctive art of the era, the Aten appears as a sun disk whose rays deliver blessings and eternal life.

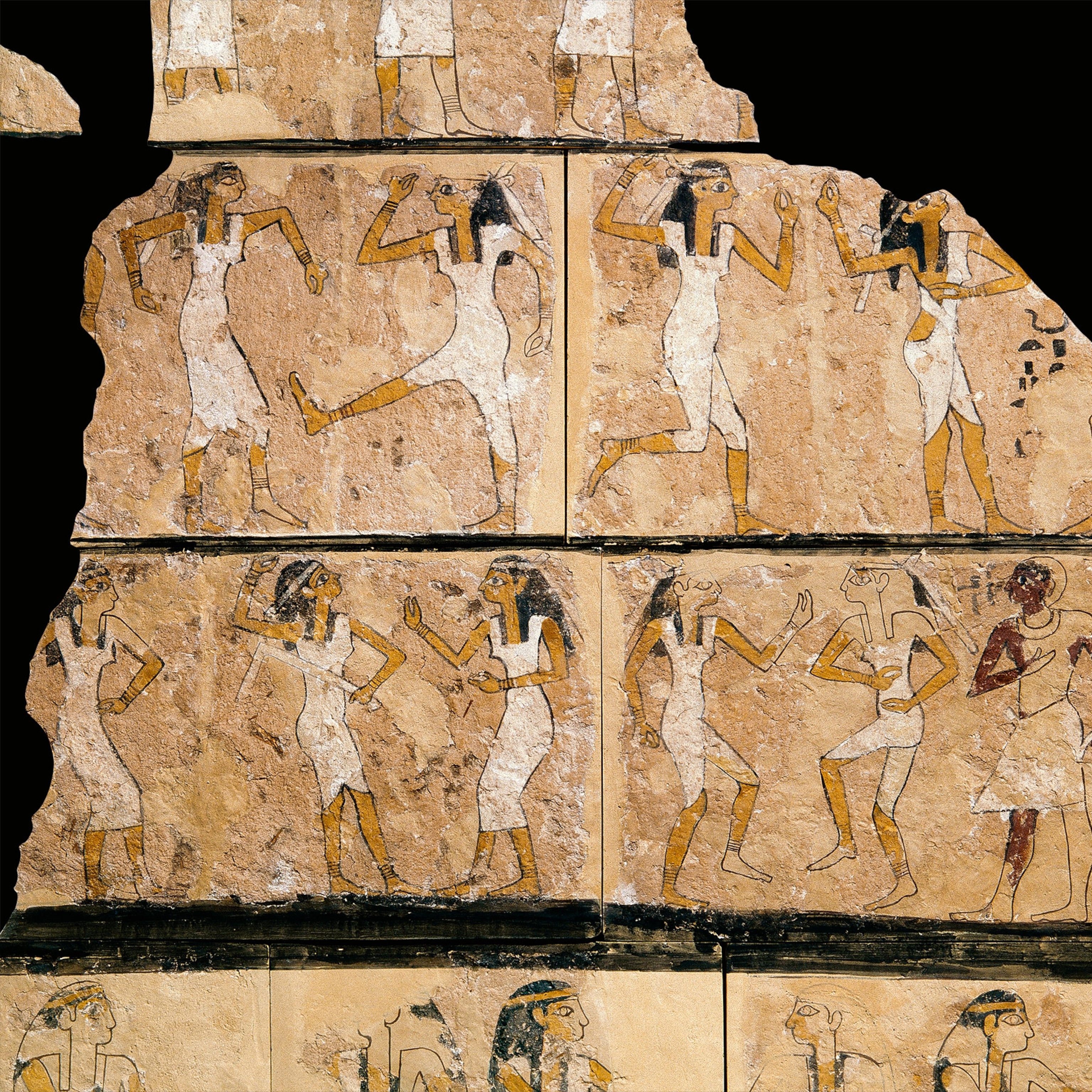

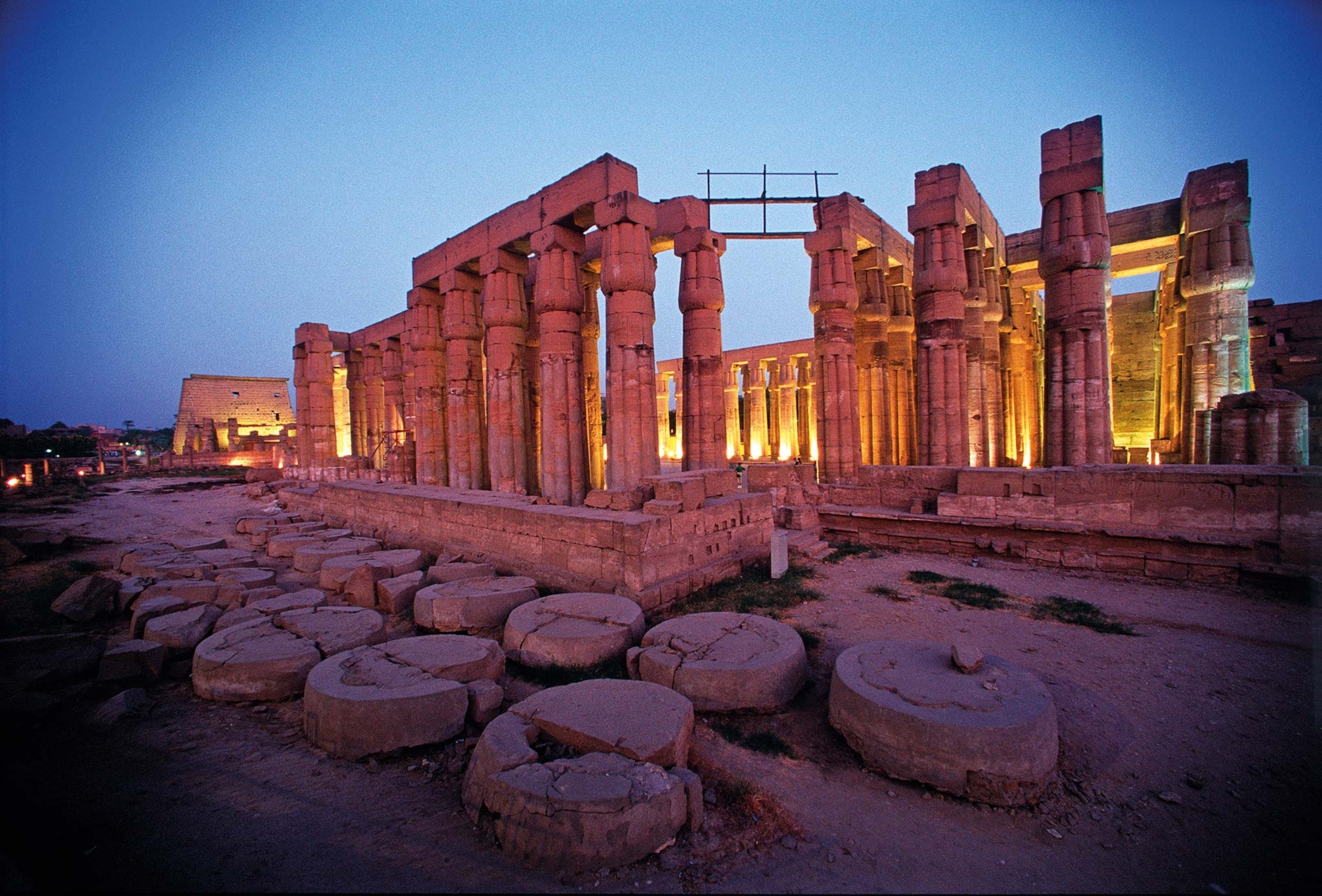

Tut’s original name was Tutankhaten, “living image of the Aten.” He was surely born in Akhenaten’s new capital, Akhetaten—“horizon of the Aten”—today the archaeological site of Amarna. Everyone at court, government officials and bureaucrats, and thousands of artisans and laborers had moved to Akhetaten with the king, abandoning the traditional capital of Thebes, modern Luxor. That occurred in the midst of a religious revolution in which Akhenaten made the Aten the country’s one official god. As centuries of polytheistic tradition were suddenly upended, with the old gods falling out of favor, confusion and terror must have gripped the country.

(Meet King Tut’s father, Egypt’s first revolutionary.)

According to the results of DNA tests published in 2010, a decayed mummy found in tomb KV55 was Tut’s father. Some Egyptologists believe that it was Akhenaten, based largely on royal epithets on the coffin, but other experts have their doubts. They wonder if the bones might belong to someone else—perhaps a shadowy figure named Smenkhkare, who may have been Akhenaten’s brother.

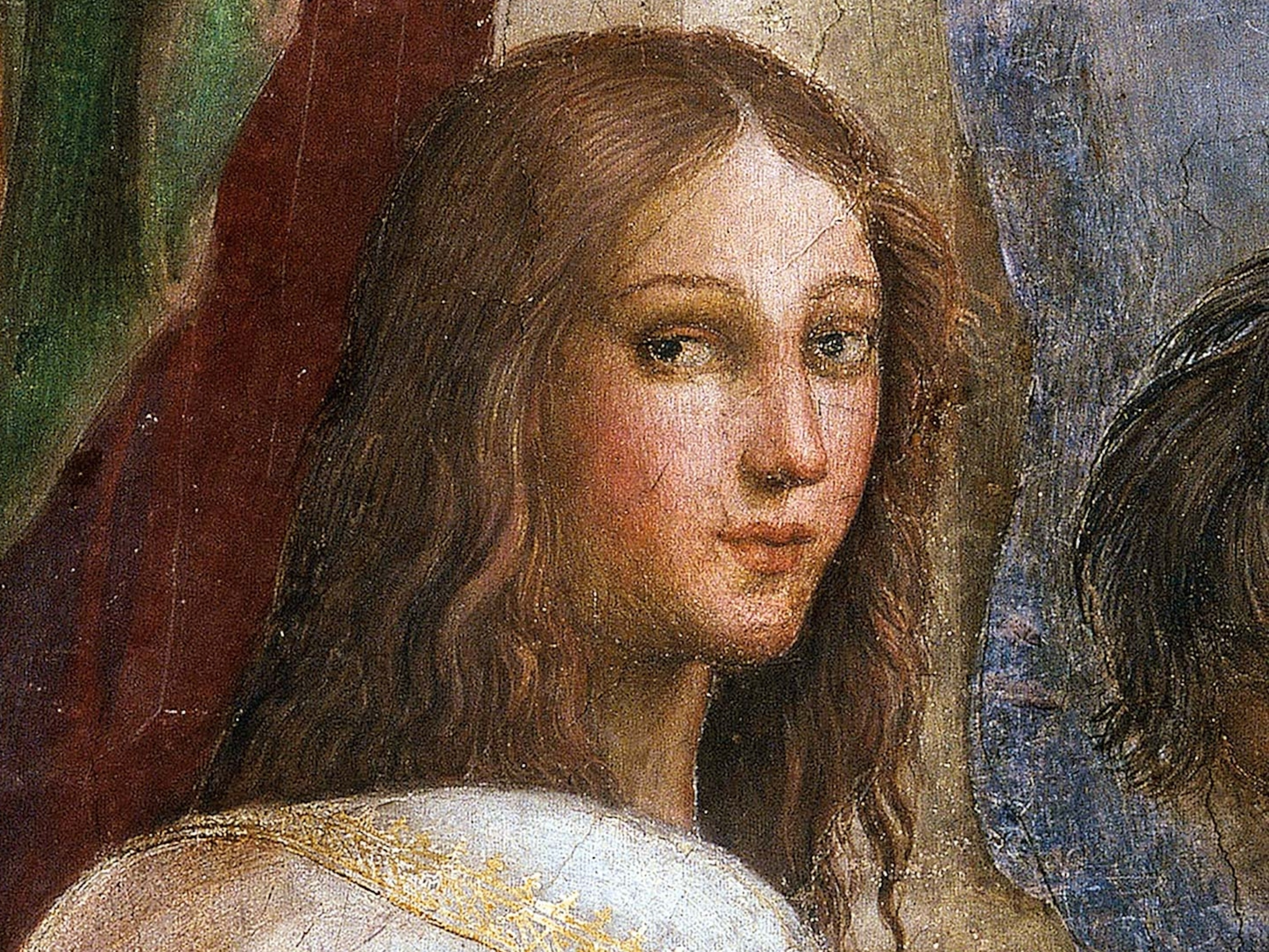

Like many ancient Egyptian royals, Akhenaten had more than one wife. His queen was the famously beautiful Nefertiti, and together they had six daughters: Meritaten, Meketaten, Ankhesenpaaten, Neferneferuaten Tasherit, Neferneferure, and Setpenre. History shows that the royal couple probably did not produce a son needed to secure the succession. Archaeologists would have to look elsewhere for the identity of Tut’s mother.

Akhenaten’s other wives included a woman named Kiya, possibly a foreign princess, who was once thought to be a possible candidate for Tut’s mother. But DNA tests revealed that Tut was the son of a female mummy found in KV35 (known as the Younger Lady). That woman was also the sister of the man from KV55, Tut’s father, making Tut the product of sister-brother incest. The names of five of Akhenaten’s sisters are known, but which one might be the woman from KV35 is a mystery.

(This Egyptian queen's tomb lay untouched for more than 4,000 years.)

Who was next in line?

The name of Akhenaten’s immediate successor is also uncertain. Nefertiti may have been a co-ruler with her husband at the end of his reign, which lasted about 17 years. She then could have continued to rule in her own right after his death, perhaps even taking a man’s throne name to mask being a female ruler.

But there’s another person in the mix here—Smenkhkare. Did he become king upon Nefertiti’s death? Or did Nefertiti not rule at all, and it was Smenkhkare who succeeded Akhenaten? His rise to the top would make sense. He had the right lineage, and he may have been married to Meritaten, the oldest of Akhenaten and Nefertiti’s daughters.

Whoever preceded Tut didn’t rule for long, and the prince became king when he was about nine years old. As an heir apparent, he may have been schooled in all the things a pharaoh would need to do to keep the gods happy and Egypt prosperous. But at such a young age he couldn’t have been ready to rule or to deal with the political and religious chaos left by Akhenaten.

Tut must have had advisers, and they apparently were focused on restoring Egypt to what it had been before Akhenaten’s reign. They moved the court back to Thebes, reinstated the old gods, and restored ma’at, the foundational Egyptian concept of order and things as they should be.

(Egypt’s new billion-dollar museum is fit for a pharaoh.)

What killed the Boy King?

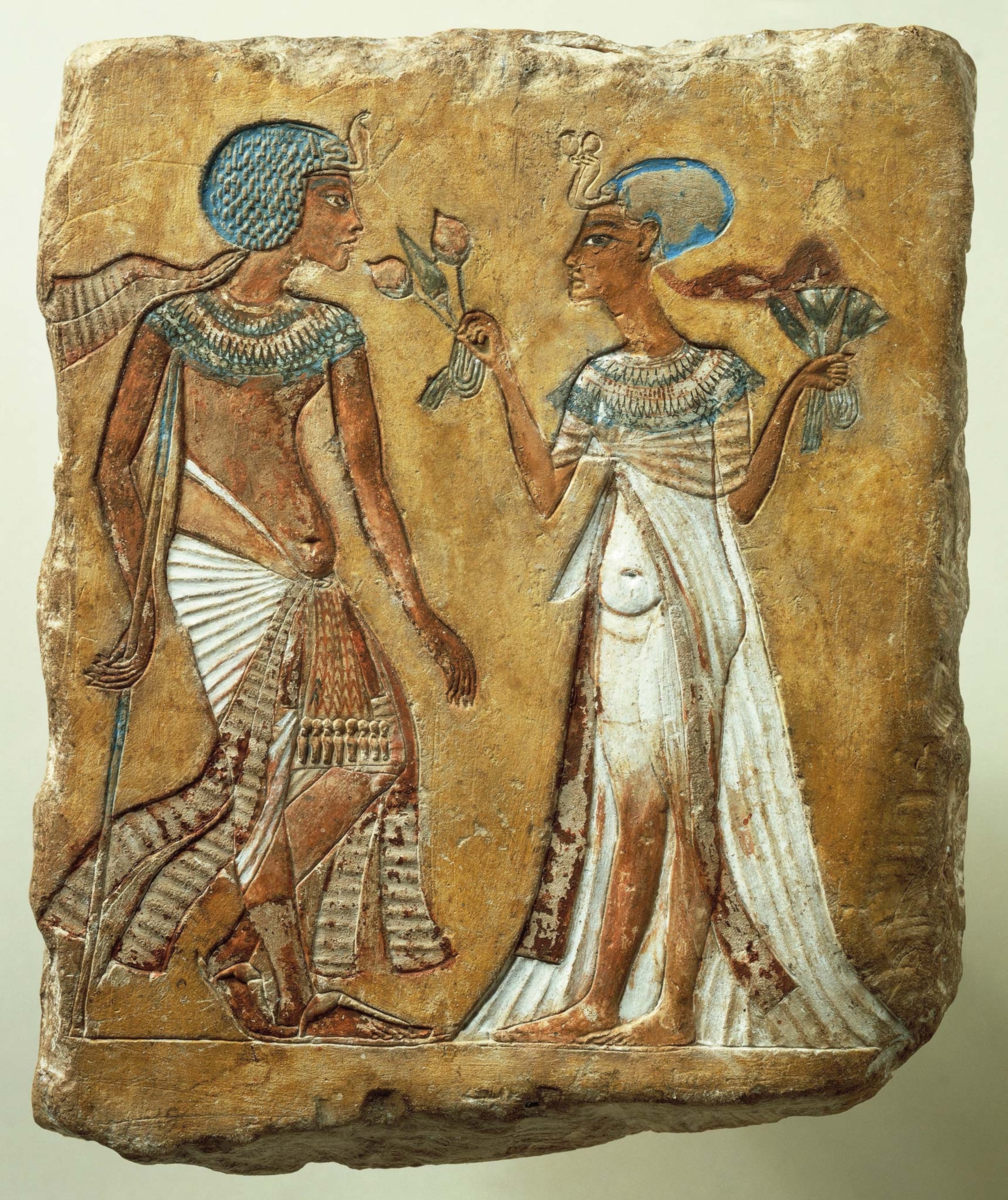

When he came of age, Tut married, as all pharaohs should do. His wife was Ankhesenpaaten, Akhenaten and Nefertiti’s daughter. If Akhenaten was, indeed, Tut’s father, that meant Tut married his half-sister—another point of incest in the family tree. By this time Tut and his wife had changed their names to reflect the country’s religious reset and the rehabilitation of Amun, a powerful god based in Thebes. They were Tutankhamun, “living image of Amun,” and Ankhesenamun, “she lives through Amun.”

(Nefertiti was more than just a pretty face.)

Although incest may have been an attractive strategy for keeping power in the family, it was genetically risky. In this instance the risk did not pay off. Two fragile, mummified fetuses were discovered in King Tut’s tomb, each with her own tiny nested inner and outer wooden coffins. They were his daughters with Ankhesenamun. The young couple tried to do their duty and produce an heir, but couldn’t. The shared genes they inherited probably made it impossible for them to conceive a healthy baby, thus setting up the inevitable end of the 18th dynasty.

Given his genetic background, it’s not surprising that Tut was frail. Slight of build, he stood about five feet five and may have had ailments that impeded his ability to walk normally. Also, the 2010 test results showed that he suffered from chronic malaria, the result of living near the mosquito-filled Nile marshes.

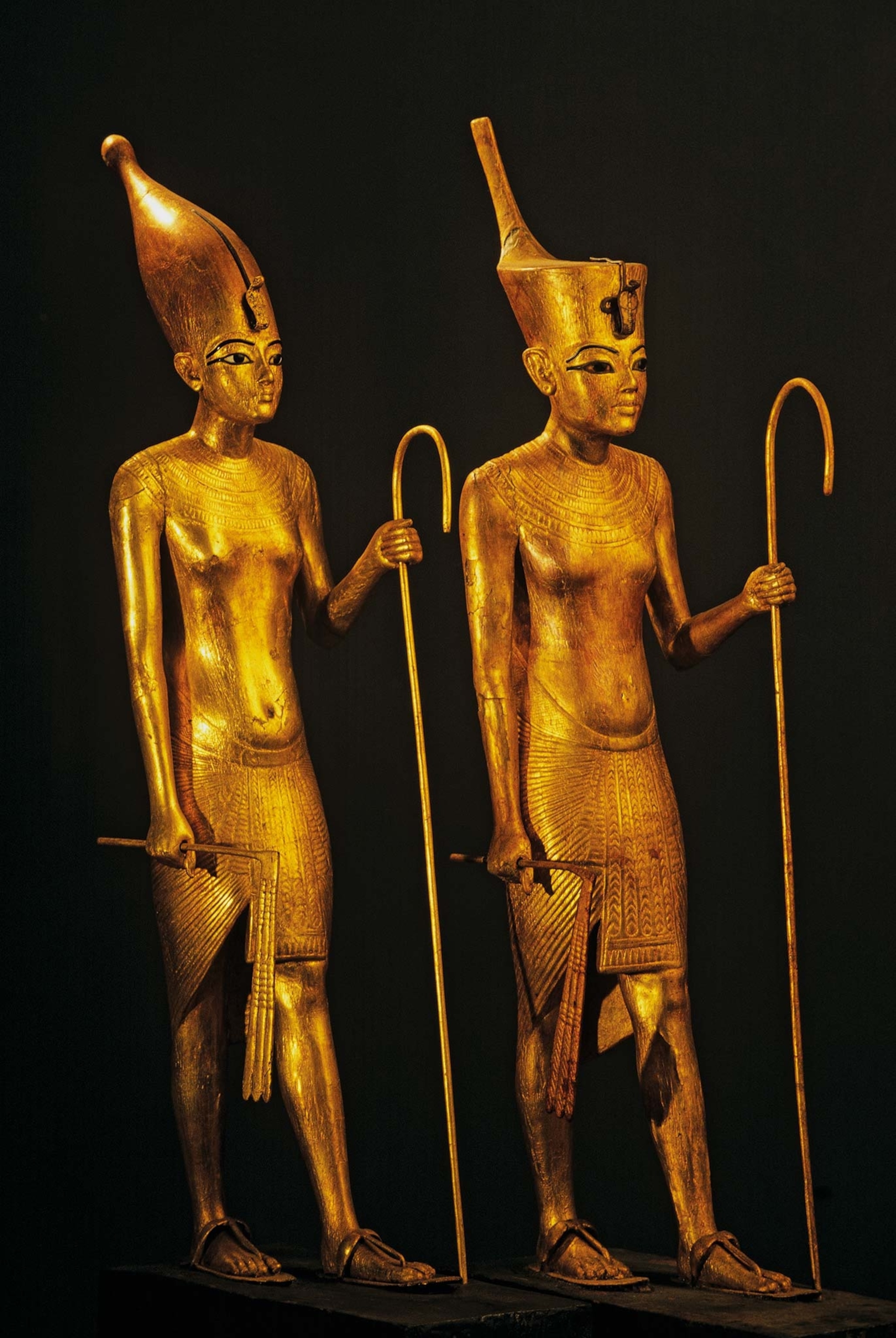

Still, it must have been a shock when he died at the age of 19. A scramble ensued to find a burial place, and to surround Tut with the things a pharaoh would need for the next world. In their hurry the officials chose a tomb far too small for a pharaoh, included artifacts that had been made for other royals, and hacked at the wooden coffin to make it fit in the stone sarcophagus.

This was a fraught time in Egyptian history. The royal succession that led to Tut’s time on the throne had probably been tumultuous. And now, the young king had died without leaving an heir. In that context, some historians have imagined intrigue and skullduggery, with some suggesting that a rival’s blow to the head killed Tut.

Tut's treasures

(Who was Egypt's first pharaoh?)

A CT scan conducted in 2005 put that idea to rest. The fragments of bone that a previous x-ray had revealed inside Tut’s head were the result of a hasty mummification, not a bashed-in skull. A likely cause of death was a broken leg that pierced the skin. The wound became infected, leading to sepsis. The accident could have been caused by a chariot crash, a battle injury, even an attack from one of the hippos that wallowed in the Nile.

Heartless pharaoh

What was the queen's fate?

Around this time, an Egyptian queen whose name is unknown sent a letter to Suppiluliumas, king of the Hittites, Egypt’s archenemies.

“My husband is dead, and I have no son,” she wrote, asking the king to send a prince for her to marry. Some experts believe that queen was Ankhesenamun. Suppiluliumas must have seen some political advantage to such a union and sent off a son named Zannanza. The prince died mysteriously en route, however, with the cause of death lost to history.

Given the Game of Thrones climate of the time, murder is certainly a possibility. Some think the culprit was an Egyptian general named Horemheb, who would become king after Tut’s successor, Aye. Others even go so far as to speculate that Aye was the mastermind, making a desperate, end-of-career power grab once word reached Egypt about Zennanza’s untimely end. Aye may have married Ankhesenamun to secure his own place on the throne. It was all in the family: Queen Tiye, Ankhesenamun’s grandmother, was likely Aye’s sister.

The evidence for the marriage is a ring with dubious provenance. “Mr. Blanchard of Cairo acquired last spring, from an unknown site in the Delta, a blue glass finger-ring which has engraved on its bezel . . . the prenomen of King Ay and the name Ankhesenamun, both names being written in cartouches,” wrote British Egyptologist Percy Newberry in a 1932 report that included a sketch of the cartouches. The Egyptian Museum in Berlin may have acquired that same ring from a different owner in 1973. Such artifacts have often changed hands from one private collector to another without leaving a traceable chain of custody.

In any case, Aye was an old man and didn’t live long after he became king. Left without an official role, Ankhesenamun vanished from history. DNA testing suggests that she may be one of the two female mummies found in KV21.

Is there more hidden in Tut's tomb?

In a saga filled with intriguing questions, one more has arisen recently: What may lie behind the painted walls of King Tut’s tomb? In 2015 British Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves suggested that Tut had been hastily buried in chambers that belonged to an earlier royal tomb complex. That preceding burial would have been sealed off, and would now be hidden just beyond Tut’s own burial chamber. The proposed occupant? None other than Nefertiti.

Experts were skeptical at first but then began to wonder whether an adjacent burial might even hold Meritaten. Ground-penetrating radar (GPR) scans were carried out, but the results were inconclusive. The limestone in the Valley of the Kings is notoriously inconsistent, as hard and slick as marble in some places and as crumbly as dried mud in others. Such irregularities may have prevented the GPR from getting the clearest picture of what lay beneath the ground.

(Hieroglyphics were a mystery until this man solved the riddle of the Rosetta Stone.)

If additional tests are conducted in the future, they might find nothing at all. But many people still hope they will reveal a royal tomb untouched for more than 3,000 years. Such a bombshell would show, yet again, that the Valley of the Kings should never be counted out as a source of astonishing archaeological treasures. Theodore Davis would have discovered that if he had only had a bit more faith.

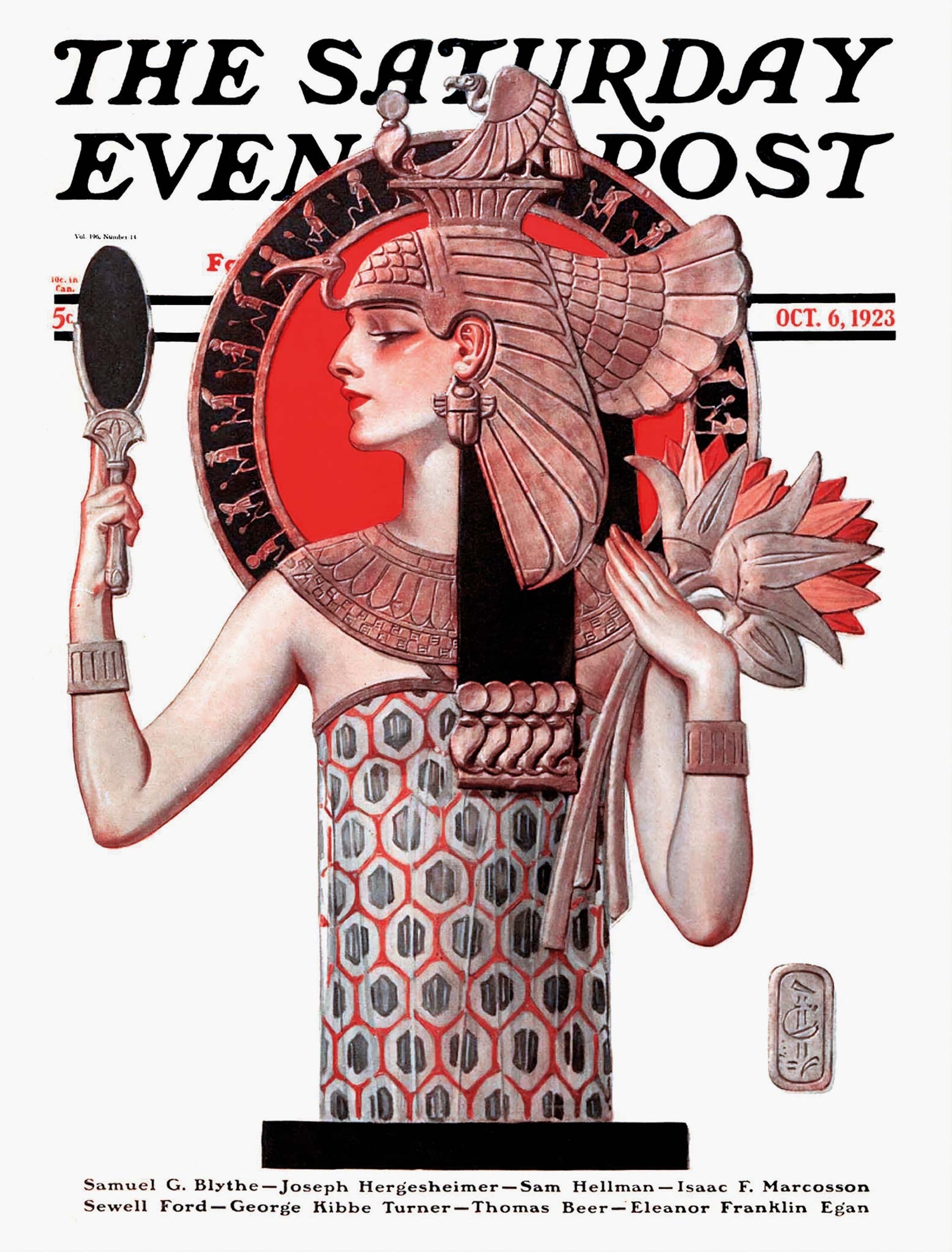

Tutmania in the twenties