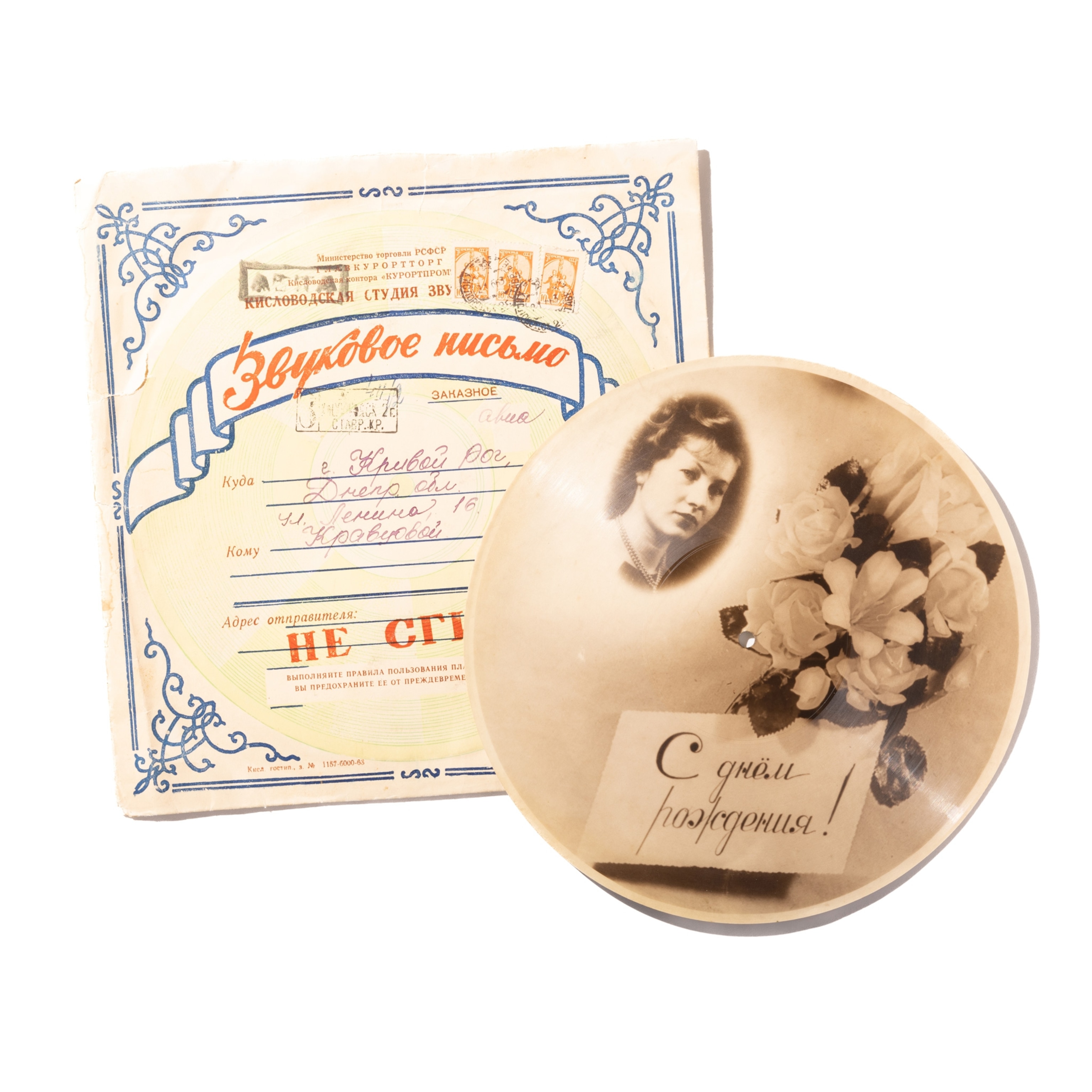

How were the first 'voice mails' sent? In envelopes

Decades before mobile phones or answering machines, loved ones shared voice messages over long distances by mailing small custom records.

“Hello Mother, Dad, and Blanche,” a quiet voice says above the cracks and pops of an old vinyl record, which has clearly been played many times over. “How’s everything at home? I’m recording this from Dallas…from this very little place where there are pinball machines and many other things like that…”

The disc is small, seven inches across, dated October 1954. The faded green label shows that the speaker’s name is “Gene,” the recording addressed to “Folks.” Gene suggests in his minute-long message that he is traveling—“seeing America”—and tells his family not to worry about him.

“I should complete my trip sometime around Thanksgiving,” he continues in a second recording made in Hot Springs, Texas, not too long after his first one. “I hope you received my letter and I, in turn, hope to receive some of the letters that you sent me. It’s been a very long time since we’ve corresponded, and I’m looking forward to hearing from you very, very much.”

This largely forgotten sound is one of the world’s early “voice mails.” During the first half of the 20th century, these audio letters and other messages were recorded largely in booths, pressed onto metal discs and vinyl records, and mailed in places all over the world. Best known today for playing music at home, record players were then being used as a means of communication over long distances.

Reach out and touch someone

The idea of transporting a person’s voice had loomed large in the human imagination for some three centuries before it was finally achieved with the invention of the phonograph in the late 19th century. Historical documents from the Qing Dynasty in 16th-century China suggest the existence of a mysterious device called the “thousand-mile speaker,” a wooden cylinder that could be spoken into and sealed, such that the recipient could still hear the reverberations when opening it back up.

When Thomas Edison invented the phonograph in 1877, he envisioned a device that could reproduce music and even preserve languages. He saw, in its earliest uses, the potential to transform business, education, and timekeeping. He even imagined a so-called “Family Record”—a “registry of sayings, reminiscences, etc., by members of a family in their own voices, and of the last words of dying persons.”

But correspondence was at the top of his mind: Edison thought his invention could be used for dictation and letter writing. In the late 19th century, handwritten letters were the most common form of everyday personal communication. The telegram, which later became popular in the early 1900s, was used for shorter, urgent messages—and while Alexander Graham Bell made the first transcontinental telephone call from New York to San Francisco in 1915, long-distance calling remained expensive and inaccessible to most ordinary people until the 1950s.

(Edison and Tesla's cutthroat 'Current War' ushered in the electric age)

Voice-O-Graph

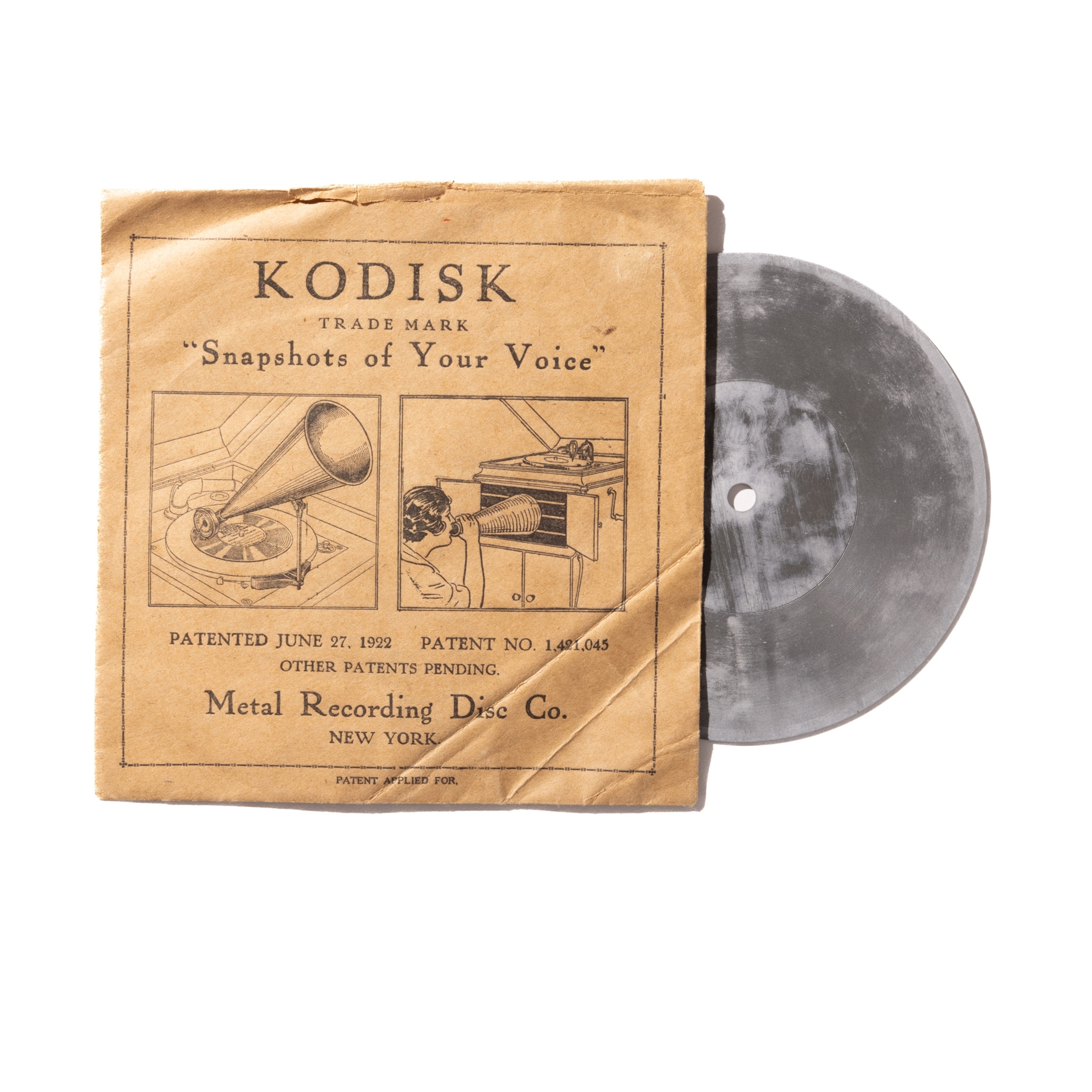

The gramophone, a later form of the phonograph developed by Emile Berliner in 1887, provided a first possibility for recorded sound being used for long distance communication. It made recording and playback possible on discs, which were easier to store, reproduce, and send. The earliest known record to have been put in the mail as a means of correspondence would be sent in the early 1920s, but the practice of sending voice mail really got going across the world in the 1930s and 1940s. It was personal and affordable as long as customers could find a recording booth or home device.

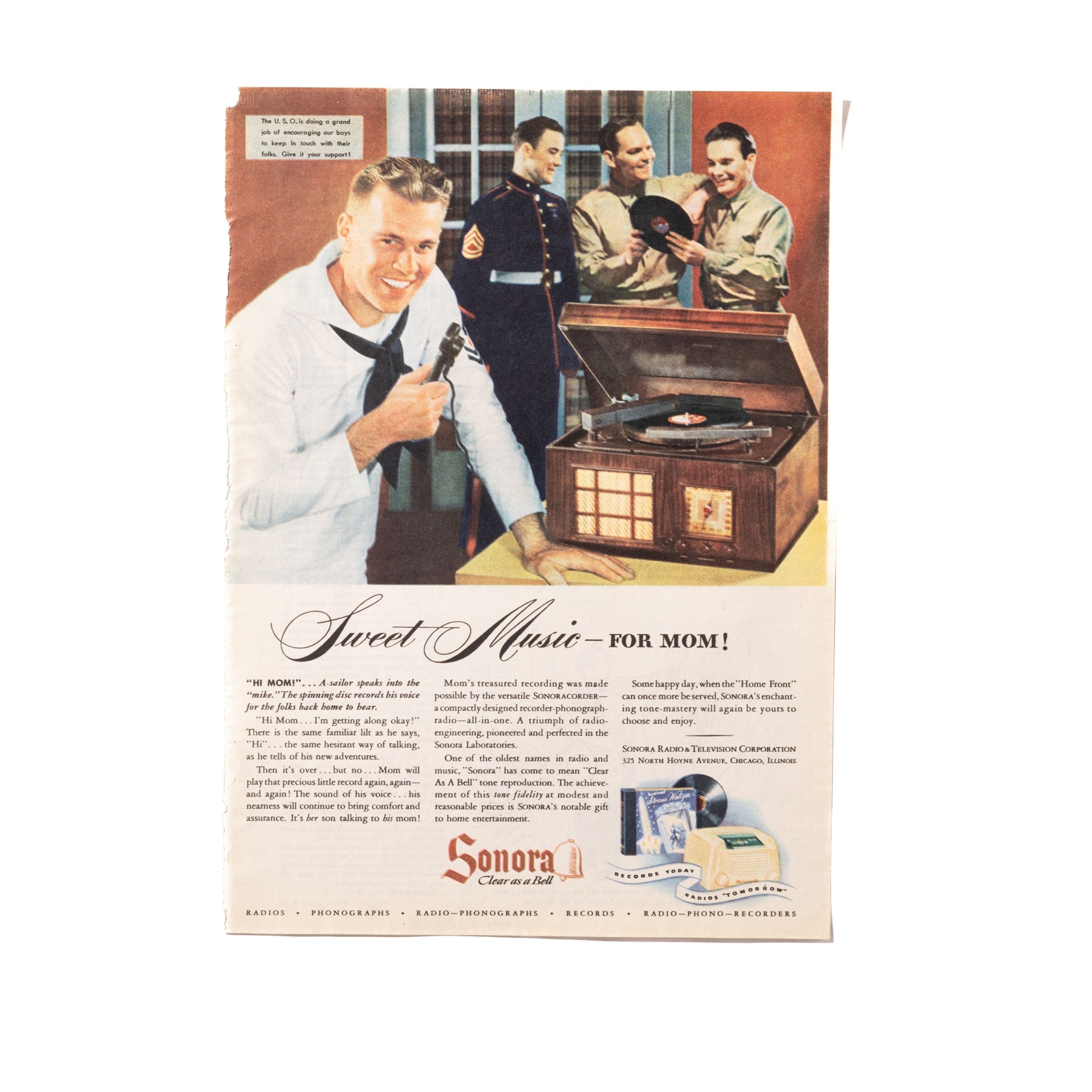

In the early 1940s, the American company Mutoscope rolled out the Voice-O-Graph machine, which vastly popularized voice mail in the United States. It was a tall wooden cabinet, shaped not unlike a modern-day photo booth, that declared, on one side: RECORD YOUR OWN VOICE! Invented by Alexander Lissiansky, these recording booths were marketed as novelties and set up at common gathering places: amusement parks, boardwalks, tourist attractions, transportation hubs, military bases and U.S.O. events. There was a Voice-O-Graph machine at the top of the Empire State Building, on the piers of San Francisco, and by the Mississippi River in New Orleans.

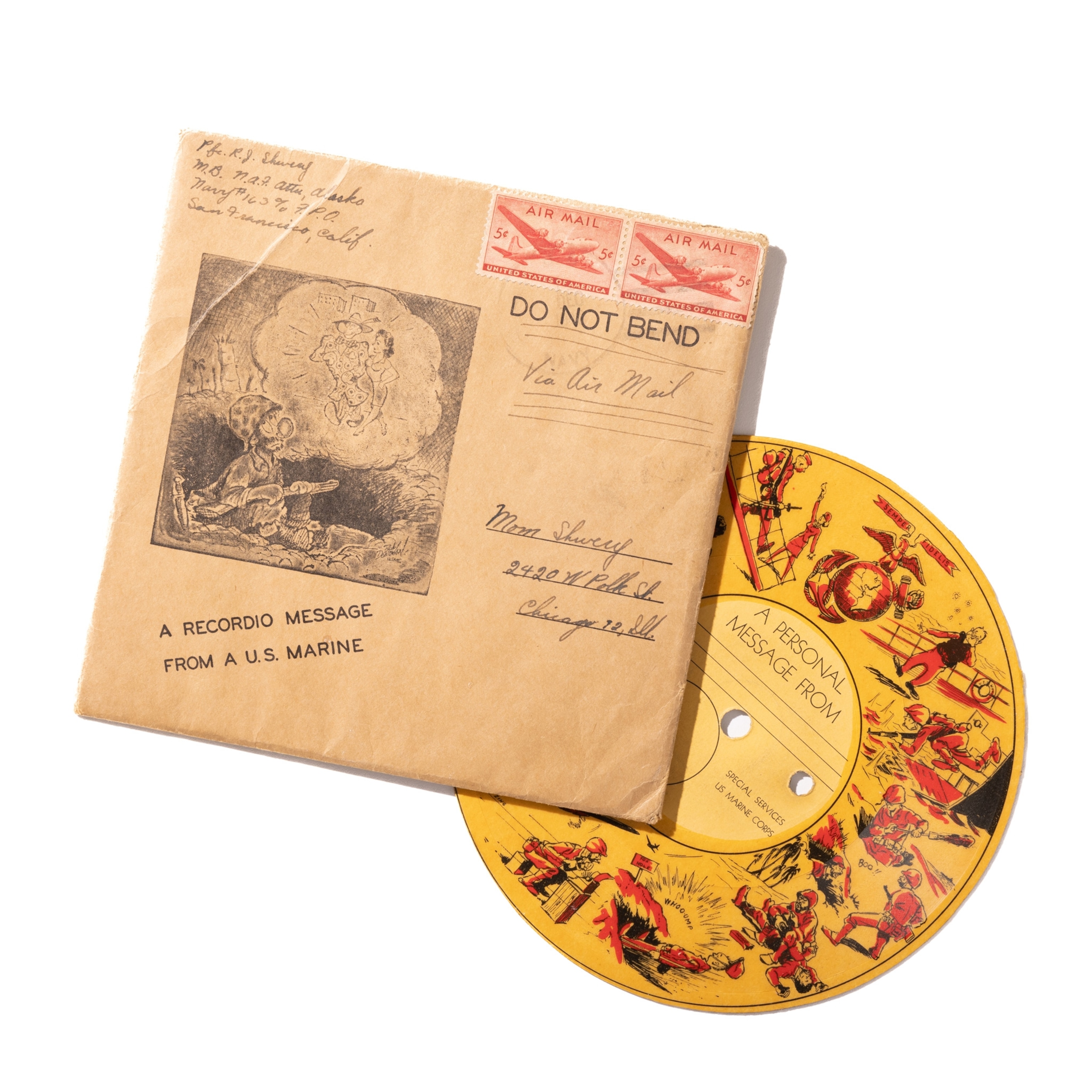

The speaker entered the Voice-O-Graph, inserted a couple of coins, and had a few minutes to record a message. Then, out popped a record the size of a 45-rpm single that was not only durable enough to be played multiple times, but also flimsy and lightweight enough to send in the mail for little more than the cost of a regular letter. Oftentimes, the envelopes themselves would come included.

Words of love

The messages people sent would range in emotion—from excitement to nervousness, joy to embarrassment. Travelers would make recordings to update family and friends on long trips. Especially during World War II, where there were recording booths on military bases in nearly every theater of the conflict, soldiers used voice mail to reassure loved ones with the sound of their voice, even if some them would never return home.

There are countless “voice mail valentines,” surprisingly intimate audio love letters. Many of the messages, sent from far away, express longing. “You keep your chin up,” a voice named Leland tells his wife in a recording dated 1945, from a booth in New York City. “All of you keep those chins up. Mike, all of us will all be home, be home where we can pick up, and carry on as we did before.” In one recording made in Argentina in the 1940s, a man plays the violin before he recites a lullaby. “Sleep, sleep my darling girl,” the man says. “It’s getting late.”

Phono-Post archive

Back then, families could listen to the messages on repeat—gathering together around the record player whenever one arrived. They could play it proudly again anytime there were guests, but with each play, the needle would scrape away at the delicate grooves until the message could hardly be heard any longer.

Today at Princeton University, professor and media theorist Thomas Levin is dedicated to preserving these sounds of the past. He maintains the world’s only archive dedicated to what he calls the “Phono-Post.” At the height of the phenomenon, there were perhaps thousands of Voice-O-Graph machines in America and many more recording stations across the world. “Millions of these audio letters were sent across the United States, South America, in Europe, in Russia, in China,” Levin says.

Levin’s office is crammed with many of the items he has collected over the years, including books, posters, and other ephemera—as well as, of course, the records themselves. Levin has already digitized some 3,000 of the discs, all of which are tucked into clear plastic sleeves and carefully catalogued. He keeps them filed into cabinets and stackable storage bins in a temperature-controlled room.

Thousands more records lie waiting to be processed in a nearly seven-year backlog that keeps growing as Levin continues collecting. He employs AI bots that constantly comb through eBay pages and bid for items on his behalf. Sometimes, he will come across people selling, knowingly or unknowingly, the voice of a relative. “I write to them and I say, you’re selling the voice of your grandfather?’” Levin says. “There’s not a sense of the value of the voice, such that people are willing to part with these objects.” Still, he offers to share an MP3 file of the recording with them, and for that, they are often very grateful.

Voices of the past

For the most part, there aren’t many celebrity voices stashed away in the Princeton Phono-Post Archive. “The bulk of the recordings in this archive are of very unextraordinary people articulating desires, wishes, fantasies, of a very quotidian sort,” Levin says. They are enormously telling, if one is willing to listen closely. Much like paper letters, these audio missives can also reveal insights about particular moments in history through the accounts of individual lives lived within them, but with added layers of sensory detail.

Historical linguists are particularly interested in “voice mail” because it provides some of the earliest-ever recorded samples of how regular people spoke—their conversational vocabulary, their pronunciation and accents, their sentence structure, their intonation. “There’s no editing. There’s no cleaning up,” Levin says. “Once the recording starts, it will run until it ends, whether you have something to say or not.” He smiled. “If you don’t have anything to say, that says something too.”

The advent of cassette tapes in the 1960s meant that services like the Voice-O-Graph quickly fell out of fashion (for a few decades, people were sending long distance messages on audiocassettes, too—a practice that became particularly common for U.S. soldiers deployed in the Vietnam War). But this voice mail phenomenon, while short-lived, holds a significant place in the history of global communication. “What we’re recovering now are the remnants of a chapter of media history, a cultural practice, that was huge, ubiquitous,” Levin says, “but has now been forgotten.”

For many people, these recordings were the first time they had ever recorded their own voice. They sound nervous, even awkward, while others even sound like they are reading from a piece of paper. Some, when faced with their very first self-recording, confronted the realization that they were leaving a highly personal trace that would likely outlive them. “People strangely, but with remarkable regularity, talk about death,” Levin says. “They’re writing to a future.” He pauses. “And one thing is known about that future: that they will not be a part of it.”