Why Timbuktu's true treasure is its libraries

This storied African city grew from a nomads’ camp into a wealthy cosmopolitan center of wisdom and learning enriched by trade in gold and salt.

For some, the name Timbuktu might conjure up romantic visions of golden treasures hidden away in a so-called lost city in northwest Africa. While these ideas may be entrancing, they do not capture the true wealth of Timbuktu. Located at the edge of the Sahara desert in modern Mali, the city’s true wealth lies in its rich history. During its “golden age” in the 15th and 16th centuries, the city of Timbuktu boasted between 50,000 and 100,000 residents. Its bustling streets were packed with merchants and their camels, coming in from trade caravans that stretched for miles outside the city limits.

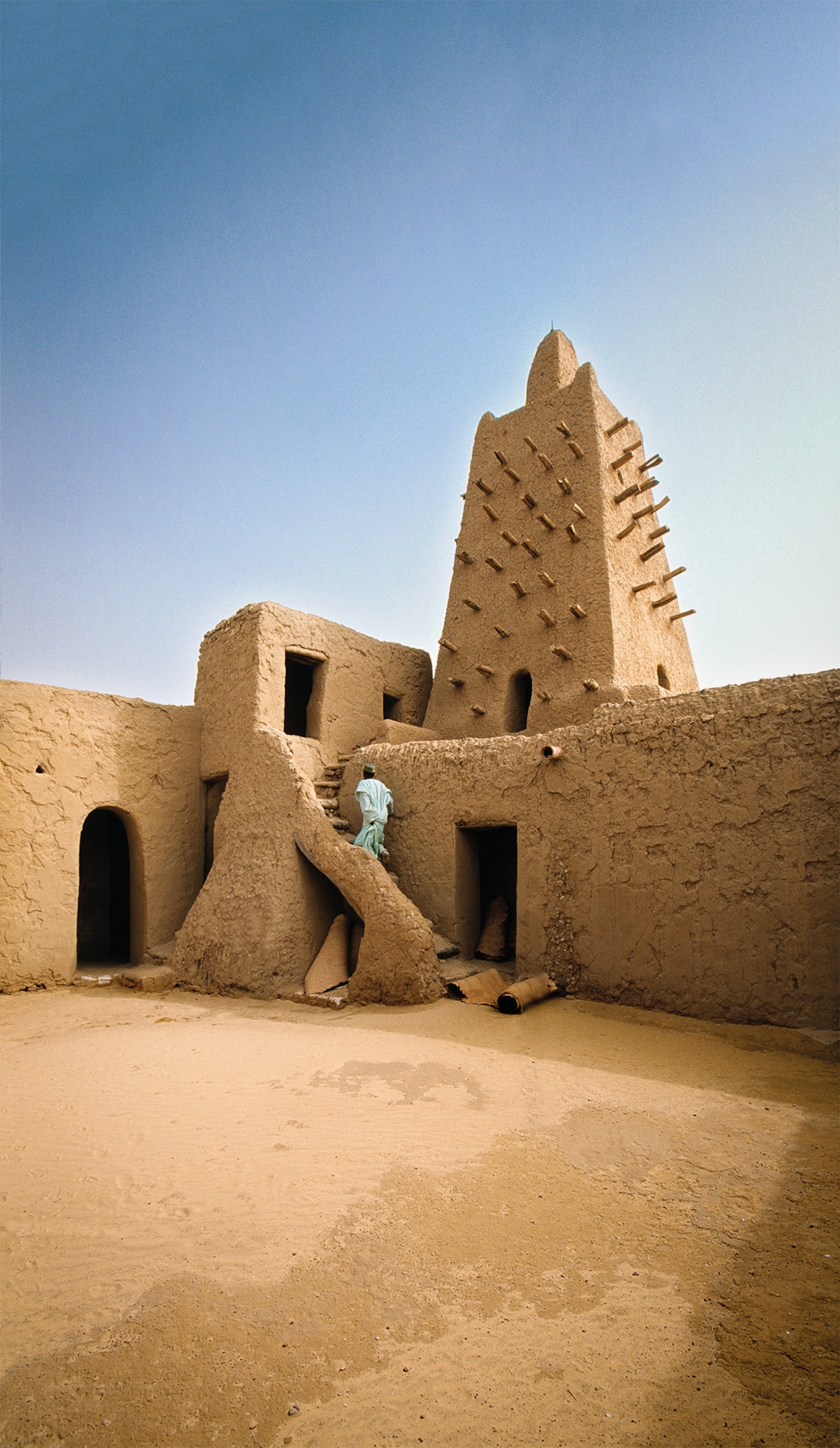

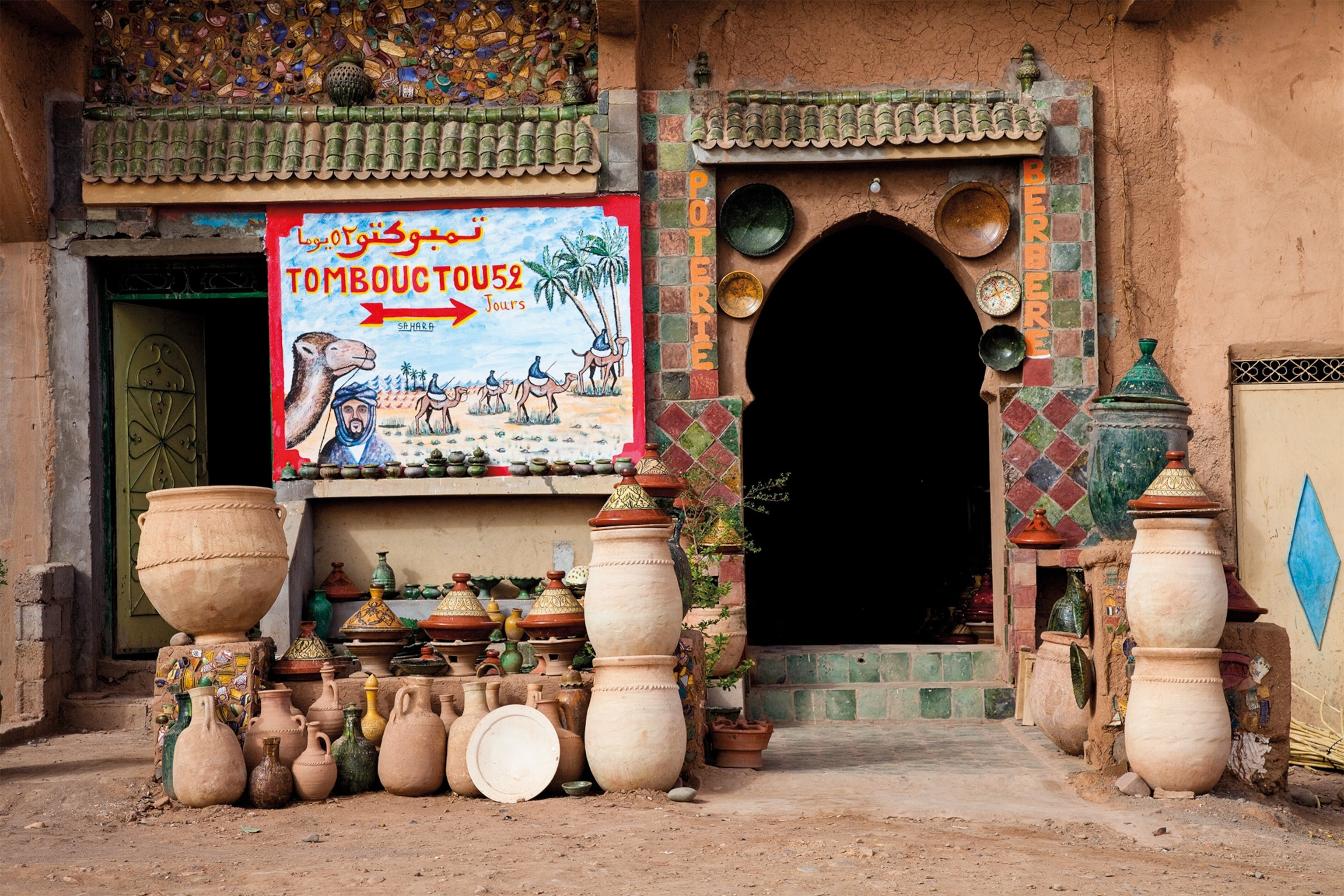

Today its population is about the same size, but the mile-long caravans are all but extinct. Sand blown in from the desert has nearly swallowed the paved road that runs through the heart of the city, reducing the asphalt to a wavy black serpent; goats now browse along the roadside in front of mud-brick buildings. It isn’t the prettiest city, an opinion that foreigners who have arrived with grand visions have repeated ever since 1828, when René-Auguste Caillié became the first European to visit Timbuktu and return alive. Rather than a city of gold, Timbuktu had become a city of subtler hues: the tans and creams of parchment, mud brick, and desert sands.

(Discover what the striking earthen city of Timbuktu looks like today.)

The mosaic of Timbuktu that emerges from history depicts an entrepôt made immensely wealthy by its position at the intersection of two critical trade arteries—the Saharan caravan routes and the Niger River. Merchants brought cloth, spices, and salt from places as far afield as Granada, Cairo, and Mecca to trade for gold, ivory, and enslaved peoples from the African interior.

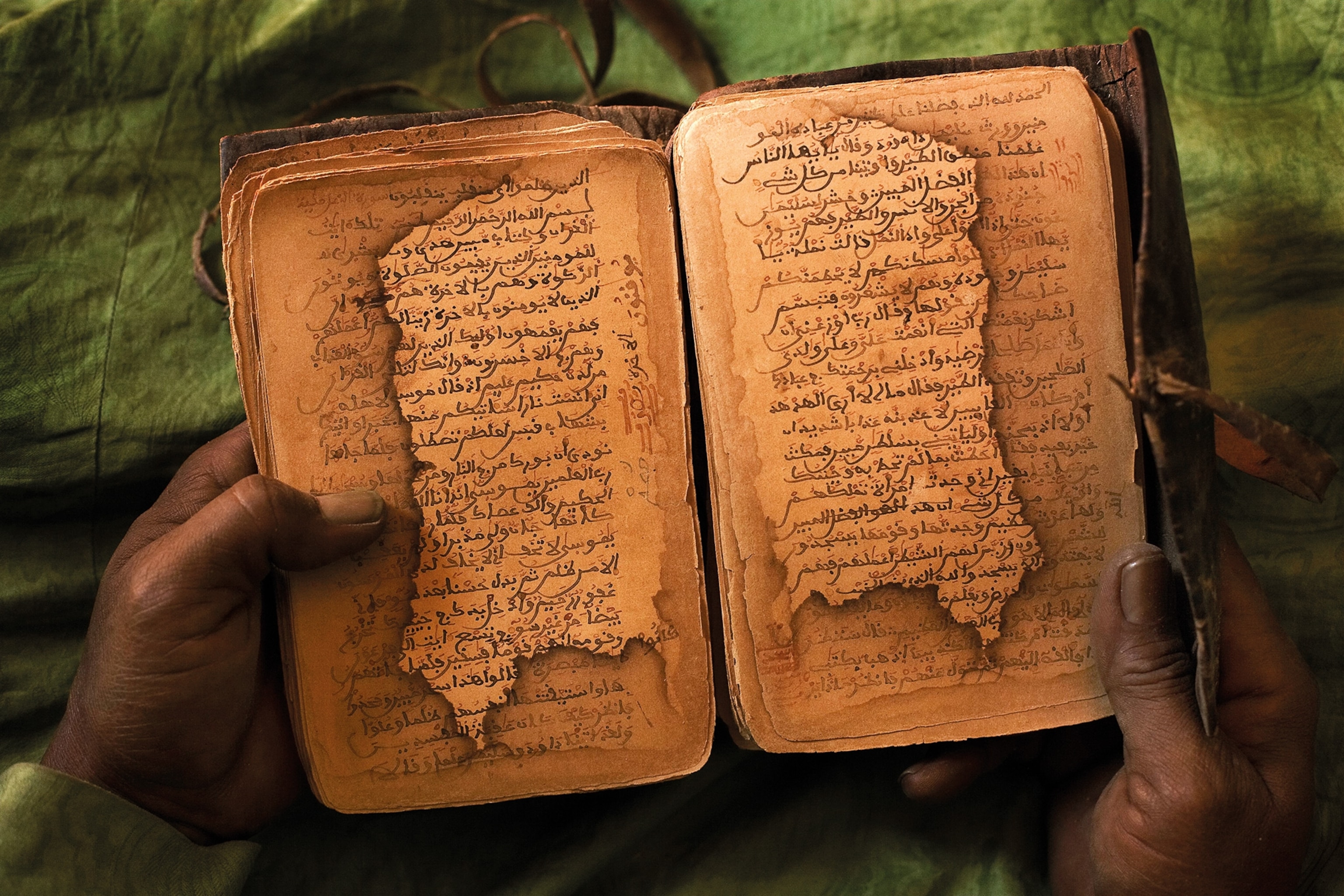

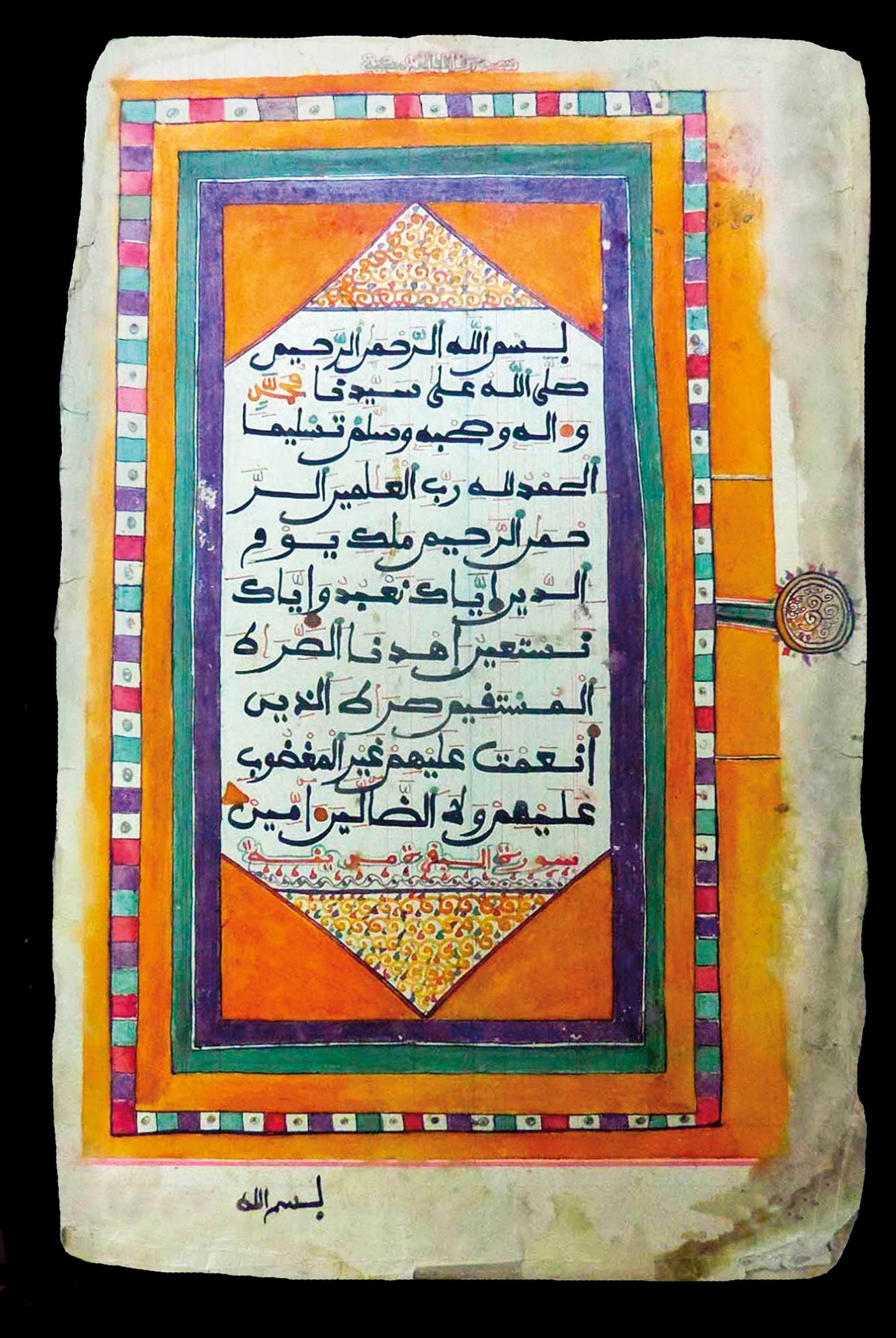

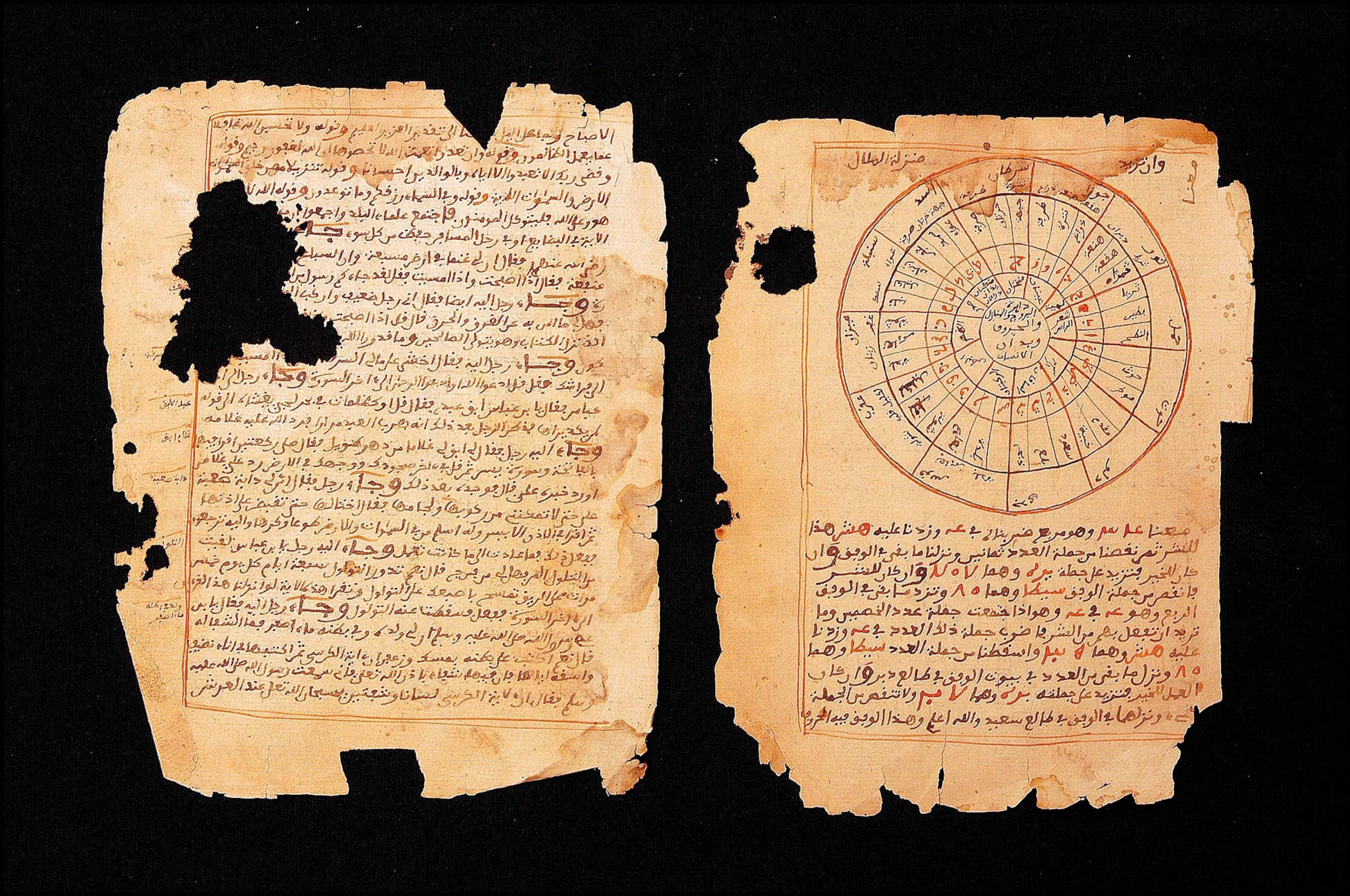

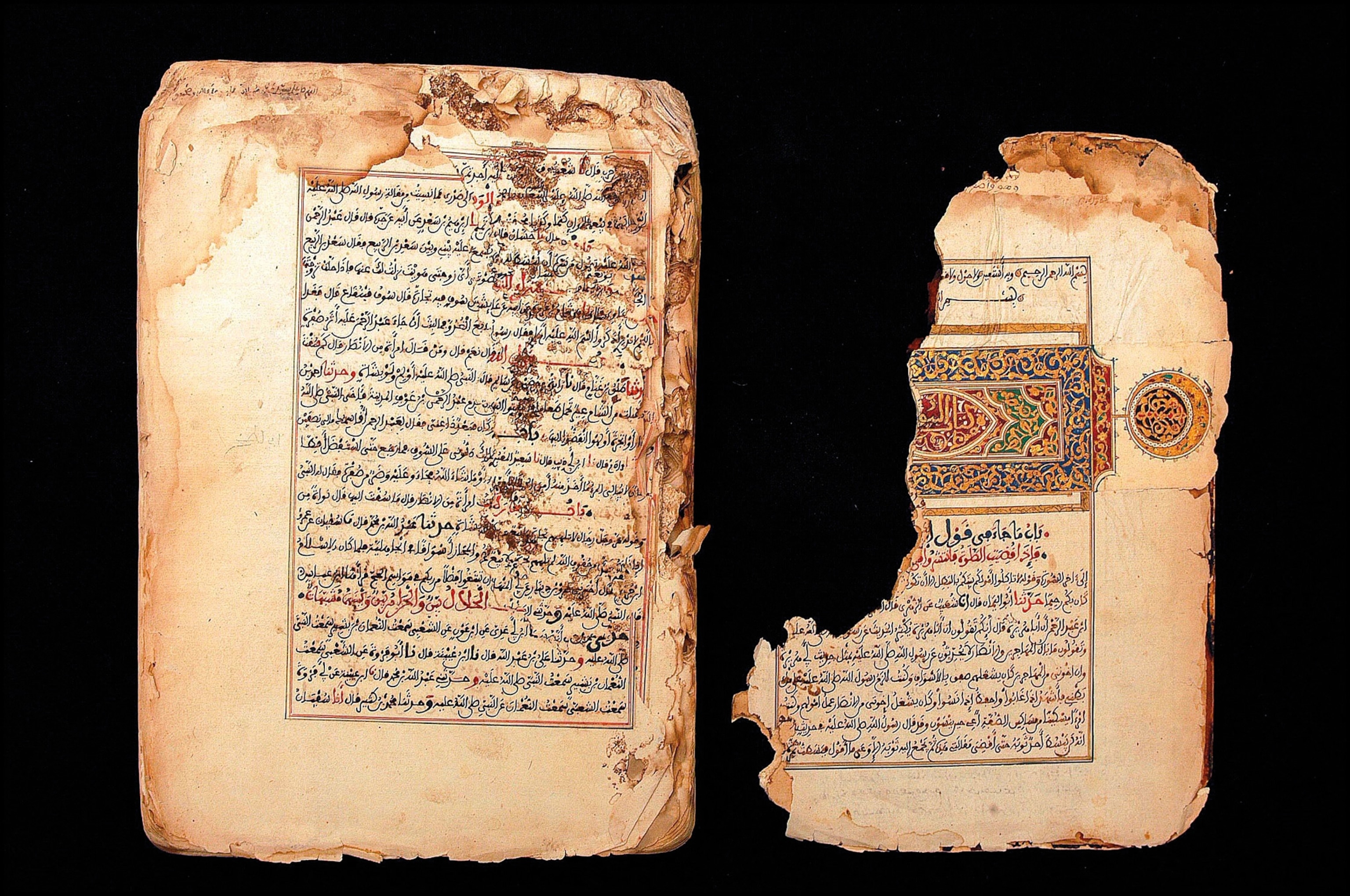

This wealth fueled Timbuktu’s rise not only as a center of commerce but also as a center of knowledge. The city would erect grand mosques, attracting scholars who in turn formed academies and imported books from throughout the Islamic world. Parchment and vellum manuscripts arrived via the caravan system that connected northern Africa with the Mediterranean and Arabia. Wealthy families, who measured their importance by the books they accumulated, had the documents copied and illuminated by local scribes. The rich built extensive libraries that contained works of religion, art, mathematics, medicine, astronomy, history, geography, and culture.

(The growth of Islam sparked a golden age of scientific discovery and advanced medicine.)

Founders and faiths

Timbuktu’s origins can be traced back to the 1100s when a clan of Tuareg, a nomadic people of northwest Africa, struck a seasonal camp near the Niger River. According to tradition, when they migrated north, they left behind the camp under the care of a woman named Bouctou, which some translate as“mother with the big belly button.” When it came time to return to the camp, the Tuareg referred to it as Tinbouctou, meaning “the well of Bouctou.” The encampment grew into a city during the centuries that followed.

Timbuktu's founders

Timbuktu was founded in the 12th century as a seasonal camp by the Tuareg, the nomadic people who controlled the caravan routes across the Sahara. Their culture has survived much turmoil since then, much of it due to European colonialism. The Tuareg found their far-flung community split by national boundaries, from Algeria and Libya in the north to as far south as Nigeria. The Tuareg strive to retain their identity: Predominantly Muslim, they speak a variety of Berber-based languages such as Tamashek, as well as Arabic and French. Although recent droughts and urbanization have challenged their traditional lifestyle, many still practice nomadism, and Tuareg communities—the men swathed in their distinctive, vibrant blue robes—still move through the vast spaces of the Sahara.

In the 700s and 800s, Islam began spreading across North Africa, from Egypt to the Maghreb, a coastal region that includes modern Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia (historically, this region is also called the Barbary Coast and its people are often referred to as Berbers). From there, Muslim traders ventured south across the Sahara desert, traveling in caravans in search of gold, ivory, and other precious goods along the Niger and Sénégal Rivers. Locals in the region began to adopt the new faith along with the wealth that trade brought to the region. These traders would reach Timbuktu and import their faith to the city.

In the early 13th century, the Malinke people lived in the small kingdom of Kangaba (located near today’s border between Mali and Guinea). Around 1225, they followed an exiled prince, Sundiata, in rebellion against Sumanguru, an unpopular leader who had alienated Muslim traders. After taking power in Kangaba, Sundiata expanded his holdings over the former kingdom of Ghana and neighboring lands rich in gold and other assets, including Timbuktu. He embraced Islam and welcomed Muslim merchants to his lands.

Under Sundiata, this region grew prosperous and would become known as the Mali Empire. Religious tolerance was embraced, and traditional polytheistic faiths flourished alongside other beliefs. Islam grew popular, especially among the merchant class. When Sundiata’s grand-nephew, Mansa Musa, became emperor, he made Timbuktu his capital. He pushed the boundaries of the Mali Empire, expanding control to the cities of Gao in the east, Walata in the west, and Jenne to the south.

In 1324 Mansa Musa left Timbuktu and embarked on a celebrated pilgrimage to Mecca that brought new attention to Mali and its wealth. His party numbered in the thousands and included as many as 500 slaves, each carrying four pounds of gold. One Arab source recorded that Mansa Musa and his attendants spent so freely in Cairo that they devalued the metal there for years to come.

Mansa Musa’s journey enhanced Timbuktu’s scholarly reputation and trade status. Architects traveled back with him, including a prominent one from Cairo who designed the Djinguereber mosque, a UNESCO World Heritage site today. Scholars from the Arab world flocked to Timbuktu, and the city was adorned with mosques and a university.

Perhaps the greatest achievement of Mansa Musa’s journey was the knowledge he obtained. He brought back an Arabic library from Mecca and poetry from Andalusian Spain. Larger libraries were created, and fragments of the “Arabian Nights,” Moorish love poetry, and Quranic commentaries from Mecca mingled with narratives of court intrigues and military adventures of mighty African kingdoms.

The Catalan Atlas

During the 1370s King Charles V of France commissioned a detailed map of the known world from the Mallorcan cartographer Abraham Cresques. He created what is now known as the Catalan Atlas, which includes a richly detailed look at the Timbuktu region and its inhabitants. The map’s legends describe local Tuareg traders (represented by a figure on a camel, below left) as a people “who cover themselves such that only their eyes can be seen; they live in tents and ride in camels.” The enthroned figure wearing a gold crown and carrying royal regalia (below, right) is Mansa Musa—“This king is the richest and noblest of all these lands due to the abundance of gold that is extracted from his lands.”

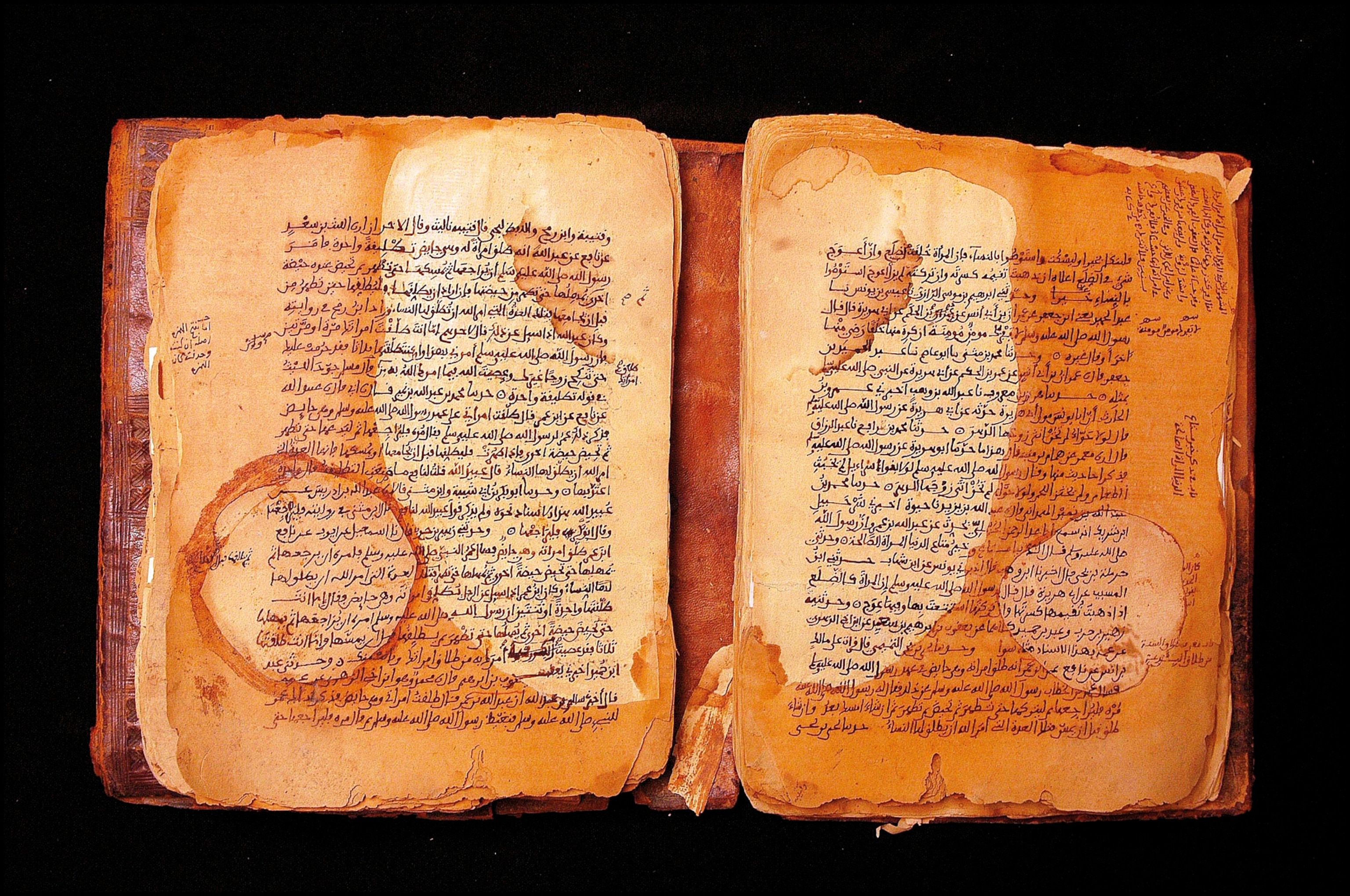

Nobody knows how many manuscripts were in the city during its golden age, in the 15th and 16th centuries, but they almost certainly numbered in the hundreds of thousands. During this golden age the city belonged to the Songhai Empire and attracted scholars from as far away as Cairo and Córdoba. Books continued to be the most treasured of objects, and myriad scribes worked throughout the city copying and writing works. Sacred Islamic texts and treatises were among the more popular, but manuscripts included a broad range of topics—from science to math, medicine, philosophy, and astronomy—and authors, including classic texts by Ptolemy, Aristotle, Plato, and Avicenna.

('Badass librarians' foiled al Qaeda and saved ancient manuscripts.)

Timbuktu’s downfall came when a Moroccan sultan invaded the city in 1591 to take control of the gold trade. His soldiers looted the libraries and rounded up the most accomplished scholars, sending them back to the Moroccan sultan. The collections of Timbuktu libraries were dispersed. Families who owned private libraries hid their books: Some were sealed inside the mud-brick walls of homes; others were buried in the desert; but countless were most likely lost or destroyed in transit.

European fascination with the city grew over time, enhanced by the 16th-century writings of Leo Africanus who visited Timbuktu and recorded his impressions in A Geographical History of Africa. The city’s reputation for mystery was also enhanced by the relative difficulty of reaching it. In 1828 French explorer René-Auguste Caillié became the first European to visit the city and return; he published his accounts in Travels Through Central Africa to Timbuctoo, and Across the Great Desert, to Morocco.

Traveler's tales

Fascination with Timbuktu was fed by the accounts of a remarkable traveler, al-Hasan ibn Muhammad al-Wazzan al-Zaiyati, known to Europeans as Leo Africanus. Born in Muslim Granada in 1485, just before that city’s fall to Catholic Spain, al-Zaiyati was educated in Fez, Morocco, and traveled across the Sahara. Later captured by Christian pirates, his extraordinary knowledge of Africa led to his entering the service of Pope Leo X as a slave. On being freed, he converted to Christianity and completed his book, A Geographical History of Africa. Its descriptions of Timbuktu—the magnificence of its court, the abundance of its books, and its use of gold nuggets as currency—would serve for centuries as Europeans’ principal source of knowledge on the African city.

Protecting and preserving

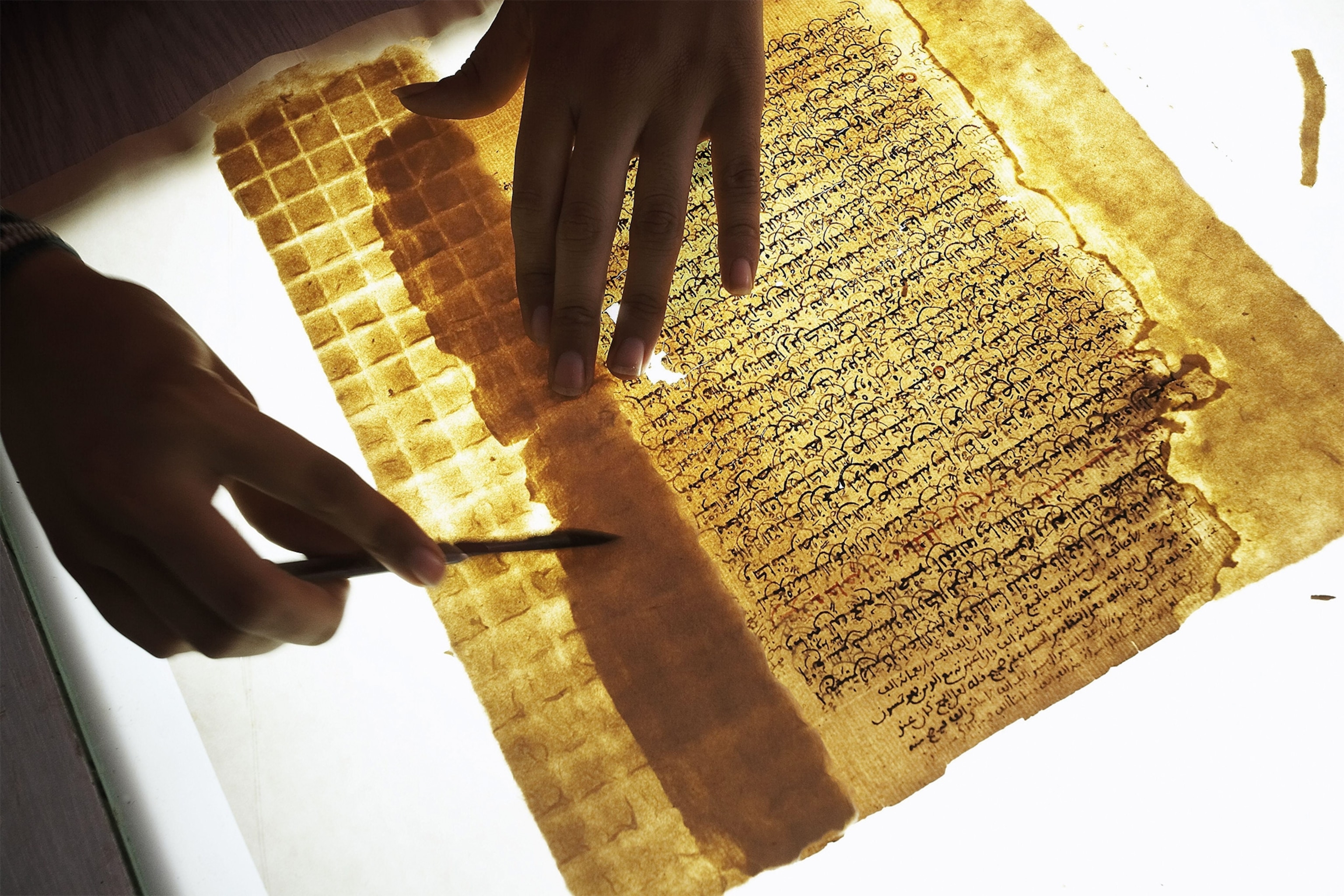

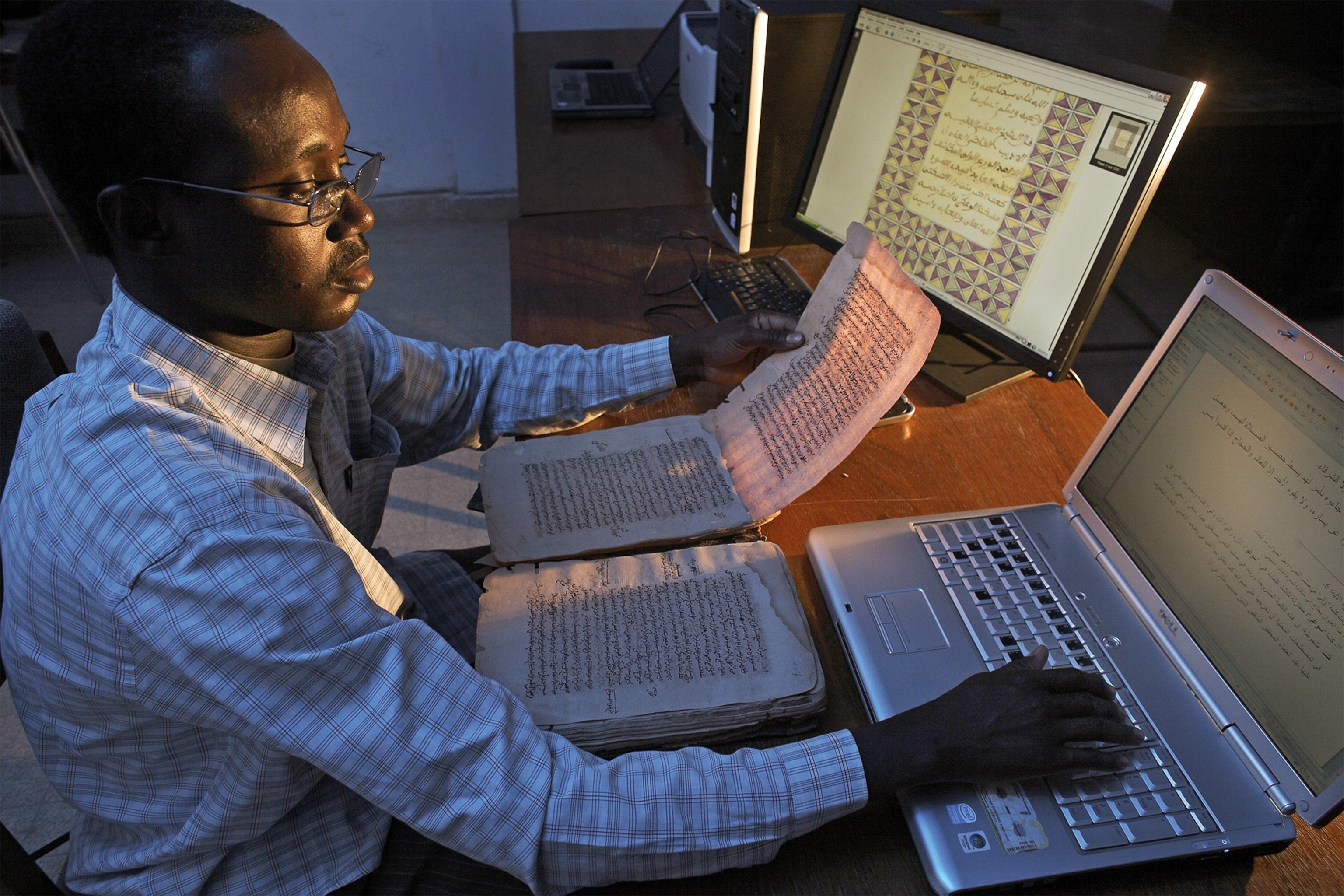

By the late 19th century, Timbuktu’s territory had fallen under the colonial rule of France. Soon after it gained its independence in 1960, the new country of Mali began to seek out and preserve the long-lost manuscripts of Timbuktu. The Ahmed Baba Institute was founded as part of this effort to save the centuries-old manuscripts. It was named for Timbuktu’s most famous scholar, Ahmed Baba al Massufi, who was held in exile in Marrakesh, Morocco, after the 16th-century takeover.

(Six years after Islamist militants were routed, Mali still struggles with violence.)

In 2012 a new peril emerged as jihadists— armed with weapons seized in Libya after the fall of Muammar Qaddafi—overran northern Mali. Overnight, Timbuktu was plunged into a nightmare, and residents feared for their lives. They knew the city’s manuscripts were in danger as well as the cultural heritage sites in the city. The police, the army, and all government officials fled, along with thousands of ordinary citizens. Looters filled the streets. Threatened with destruction as a brutal sharia regime was established, many of the city’s priceless manuscripts were spirited out of the city to safety.

During nine traumatic months, the group managed to rescue an estimated 350,000 manuscripts from 45 different libraries in and around Timbuktu; they hid them in Bamako, Mali’s capital. Other volumes were secreted away in the city itself. The jihadists were defeated in 2013. When fleeing Timbuktu, they set fire to the Ahmed Baba Institute; when assessing the damage, researchers reported that many of the ancient manuscripts escaped destruction. Today work continues to preserve these fragile treasures for the future even in the face of political uncertainty. The search for ancient texts is tantalizingly unfinished, as the full extent of Timbuktu’s treasures remains to be seen.

Correction: Oct. 7, 2021

An earlier version of this article misidentified the lead image as a medical manuscript. It has since been corrected.