Who were these ‘Queens of the Stone Age’?

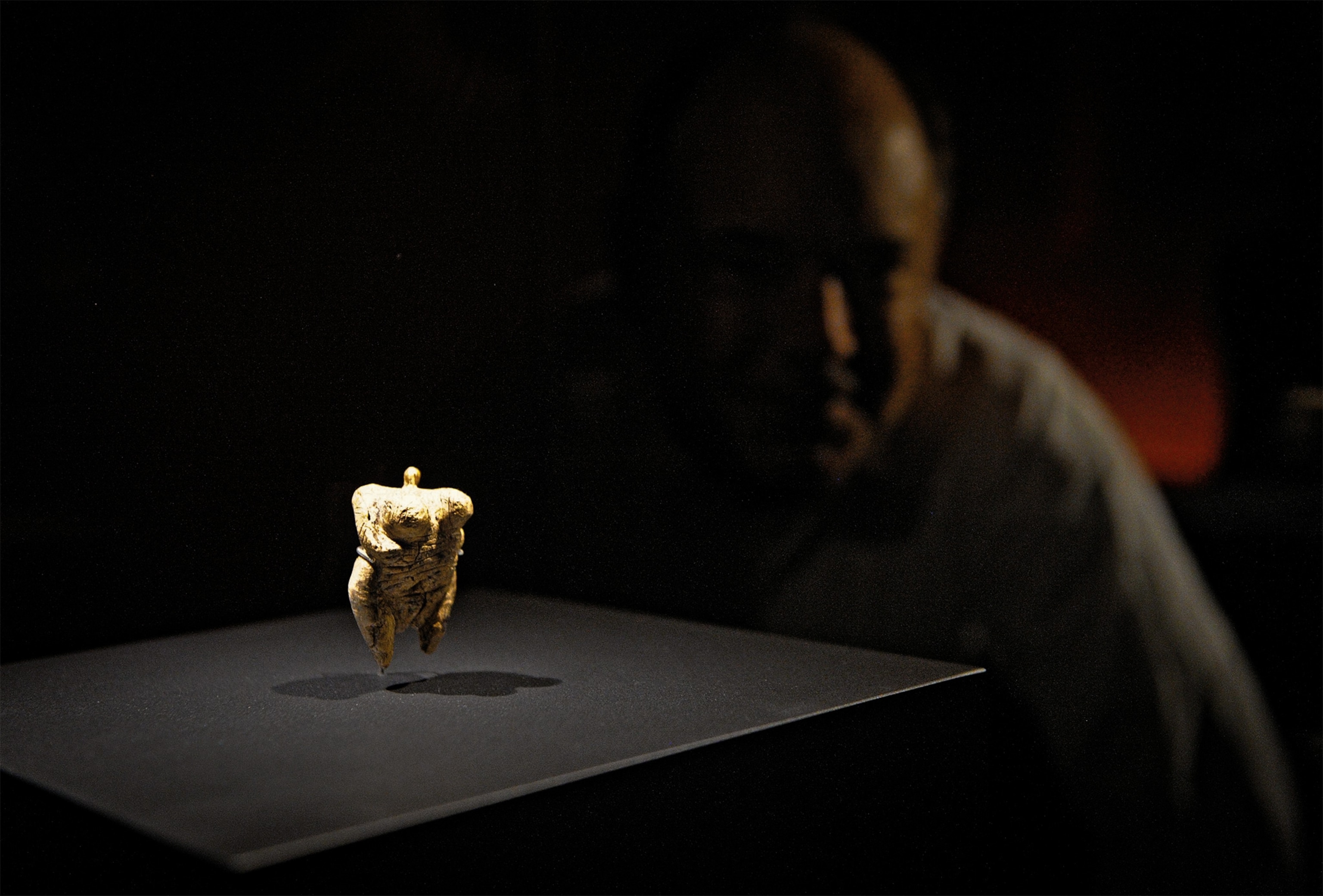

Were they goddesses—or toys? The true purpose of ancient figurines known as the “Stone Age Venuses” has stumped scholars for more than a century.

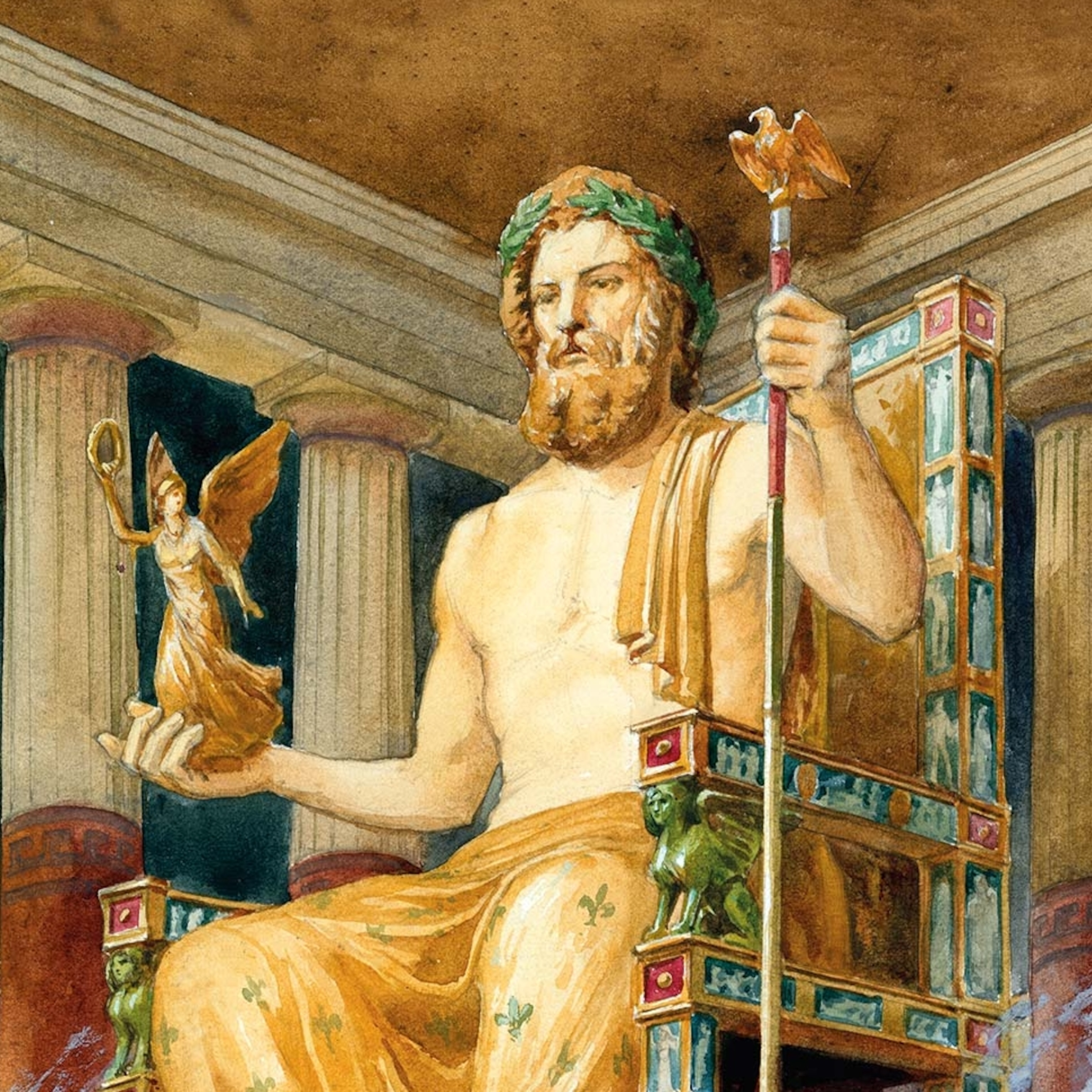

For about as long as people have been making art, female forms have been artists’ favorite subjects—from the iconic Venus de Milo, sculpted in second-century B.C. Greece, to John Singer Sargent’s 1884 elegant “Madame X.” The anonymous artists of the Stone Age were no different; small statues of women were among their most popular works of art.

Found across Europe and Asia, these female figurines created during the Paleolithic period may seem crude by comparison when gazing at the brushstrokes of Madame X’s flawless skin or Venus’s beautifully sculpted face. Roughly rendered, the Stone Age figures’ feminine traits—breasts, bellies, and hips—are large and exaggerated. Their lines are not streamlined and smooth, but rounded and swelling. Rather than sparkling eyes and smiling lips, their faces often lack distinctive features.

Collectively referred to as the Venus figurines, these statues are at the beginning of a long tradition of depicting the female form in art. They help connect modern viewers to the very distant past and the worlds of their creators some 35,000 to 14,000 years ago.

Shapes and sizes

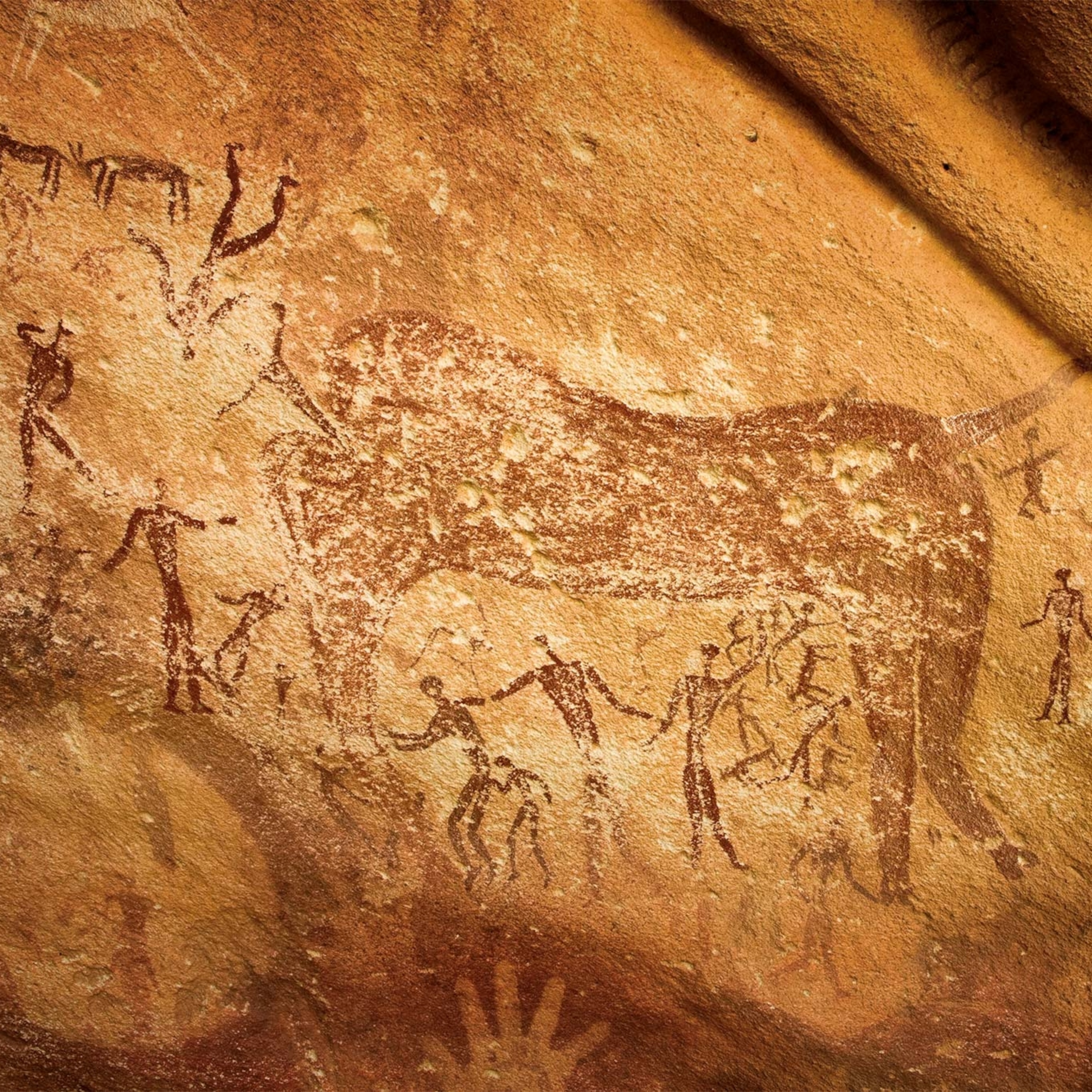

Human beings became artists about 80,000 years ago, but their first subjects were not people. Some of the earliest examples appear like abstract geometric patterns. As humanity progressed to more realistic depictions of the world around them, among their most popular subjects were animals like the horses and aurochs from the Chauvet Cave in southeastern France.

(40,000-year-old cave art may be the world's oldest animal drawing.)

Human forms begin to appear somewhere between 30,000 and 40,000 years ago in the Paleolithic period. Few works of art depicting people have survived from this time to the modern age; among the ones that have, more of them are female forms than male. Roughly 200 of the works of art now called Venuses have been found distributed across western Europe (concentrated in the Pyrenean area and southwest France, as well as in Italy); central Europe (especially around the Rhine and Danube basins); and eastern Europe and Asia (in southern Russia and as far east as Siberia).

Whether carved from stone or bone or fashioned from clay, the most notable feature among these works of art is their size. They are all tiny, measuring between two and 10 inches high, which made them portable and easy for nomadic peoples to carry from place to place.

Many of the Venuses’ faces lack well-defined brows, eyes, noses, and mouths; some are as smooth as an egg. When facial features are present, they tend to be generalized, which led scholars to believe they could be general female representations rather than portraits of specific women.

Another hallmark of these Stone Age figures is that many of them are nude, a trait that may have shocked the men who uncovered them in the 1800s. The figures do not appear demure or modest; their nudity is direct and matter of fact. A few of the figurines wear minimal adornments such as necklaces, hoods, hairnets, belts, or bracelets. Their bodies do reflect different physical types—some are slim and others curvy—while their breasts, hips, and bellies are rounded and prominent.

The oldest figure discovered (so far) comes from the German site of Hohle Fels and dates back about 35,000 years. It measures just 2.75 inches tall. The “youngest” figures found to date are about 14,000 years old. Such a wide time span demonstrates that these figures were important to prehistoric peoples for a very long period of time.

Stone Age fashions

Early discoveries

European scholars began recovering the so-called Venus figurines in the 19th century. The first one was found in 1864 by French archaeologist Paul Hurault, Marquis de Vibraye. He uncovered a three-inch-high ivory figurine at Laugerie-Basse, France. The carved nude figure is missing its head and arms, but the hips, pubic mound, and legs are well defined. Analysis shows that the figure dates to around 17,000 to 12,000 years ago.

Hurault dubbed the small statue Vénus impudique, which means “immodest Venus,” in a nod to European artworks that depict Vénus pudica, or “modest Venus.” A famous example is Sandro Botticelli’s the “Birth of Venus,” in which the Roman goddess of love and beauty modestly shields the viewer from her nudity. The prehistoric female figure from Laugerie-Basse, and many others found since then, present rather than cover up their bodies. Hurault’s naming convention caught on among other archaeologists of the time, and Paleolithic statues like these were soon grouped together as “Venuses” in the collective imagination.

The Venus of Brassempouy, discovered in 1894, is believed to be the world’s oldest depiction of a human face. Sculpted in ivory roughly 25,000 years ago, her brows and nose have been carefully rendered in miniature. The figure is sometimes called the “hooded lady” because of the pattern of lines etched into her head. Some scholars interpret them as a hood with a decorative pattern, while others believe it simply represents hair.

The Brassempouy fragment is small, slightly more than an inch in length, and scholars believe it was once part of a larger figure carved from a mammoth’s tusk. French archaeologist Édouard Piette discovered the sculpture in a cave in southwestern France. Exploring the cave in the 1890s, Piette’s team also found fragments of other anthropomorphic works, some of which appeared female.

(Ancient cave art may depict the world's oldest hunting scene.)

Perhaps the most iconic figure is the so-called Venus of Willendorf, discovered in the Danube Valley in Austria. Named after the place where it was found in 1908, the small limestone figure measures slightly more than four inches high. The artist carved several bands encircling the figure’s head which may be hair or may depict a hat. The body features large breasts, a protruding belly, rounded buttocks, and legs that taper to a point.

The artist’s visual emphasis led scholars in the 1900s to believe that the artwork must be a fertility goddess, who embodied love and beauty. Their conclusions came under scrutiny in the following decades, as debate arose over what evidence existed to support a claim that the Venus of Willendorf’s subject shared a function similar to its Roman-era namesake.

Woman or goddess

Explanations and controversies

These statues may be small in stature, but the debate surrounding them is enormous. The function and meaning of the Venuses have been hotly debated ever since the first discovery in the 19th century. Since Stone Age humans left behind no written records, scholars have had to rely on the archaeological record to formulate different hypotheses. Because this kind of evidence may be more open to interpretation, consensus among scholars has been difficult to achieve. Even the term “Venus” has come under fire since it is an anachronism (Venus would not be worshipped until the Roman era) and because it may imply that the Stone Age figures fulfilled the same role as the Roman goddess. The name has stuck in the popular consciousness, but scholars debate its continued use.

One of the earliest and most common theories was that the small carved figures were goddesses of childbirth and reproduction. They served as divine representations and were used in fertility rituals. This theory puts forth the notion that the communities across Europe and Asia highly valued fecundity and motherhood enough to display them in their works of art.

Some researchers argue that because the figures are loosely naturalistic rather than realistic and based on a specific person, they must have been endowed with ceremonial or commemorative purposes. The female figurines perhaps served as a link between the worlds of the living and of the dead in this context. Others suggested that they were ritual items, believed to possess supernatural powers and used by shamans or healers.

Other hypotheses have moved away from religious or mystical considerations into the more mundane. Some researchers’ explanations range far and wide—from erotic objects to children’s toys. It is, of course, possible that the figures were made for different purposes in different places or periods, as the geographic areas and time spans in which they have been found are both vast.

One controversial, recent theory is that some of the figures may be self-portraits, created from the perspective of a woman looking down at her own body. As research progresses and new discoveries are made, it is almost certain that ideas will continue to evolve.

Women's hands

Outlines of human hands are one kind of Paleolithic cave art that strongly connects modern viewers to their Stone Age ancestors. Until very recently, many scholars believed that men created these works, but a recent study has determined that many were made by women. Archaeologist Dean Snow of Pennsylvania State University analyzed handprint art from eight caves in southern France and northern Spain, compared the results to a reference population of people with similar ancestry to the Stone Age artists, and found that many of these ancient artists were female.

(Three-quarters of handprints in ancient cave art were left by women.)

Practical considerations

The figures’ abundant curves, large breasts, and swollen bellies have led many researchers analyzing this prehistoric art to link it to reproduction. Studies into the birth rate and demographics of today’s hunter-gatherer societies suggest that a woman who reaches 40 years of age in optimal health is likely to have had an average of six to seven children. In the Paleolithic, however, infant and child mortality rates were much higher. Exact figures are difficult to calculate, but some studies estimate that roughly 28 percent of children died in the first year of life. In addition to high infant mortality, the fatalities of women who died in childbirth or shortly after—also difficult to calculate exactly—are equally estimated to have been quite high. Maintaining populations, given these demographic trends, would be difficult.

Scholars studying the Venus figurines look to these harsh realities when forming their hypotheses about the motivations behind creating the figures. They see the robust, rounded figures as a representation of healthy mothers whose physical abundance provided the greatest possibilities for perpetuation of the group. Stone Age peoples may have believed that a well-nourished woman was more likely to produce a well-nourished newborn and to survive the rigors of pregnancy and childbirth.

Surviving the long winters

The function and meaning of the Stone Age Venuses have long been debated, and a new hypothesis has entered the fray. Rather than seeing the figurines as deities or embodying aspects of sexuality and fertility, researchers are looking at them as emblems of survival. Many of these figures were created during the Last Glacial Maximum, a time in which temperatures plummeted, glaciers expanded, and food resources became scarce. A team of researchers from the University of Colorado and the American University of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, studied the Venus figurines and noted that more voluptuous artworks with prominent fat deposits on the hips, buttocks, and bellies were found closer to glaciers. The farther away a population lived from an ice mass, the more proportions decreased. They concluded that fuller-figured Venuses served as symbols of survival in harsh, frigid conditions because the bodies of these “overnourished” women could withstand food shortages during the long winter.

Some figures, however, do not fit neatly into these assumptions. Figures found in Russia and Siberia are markedly different. They were more recently produced, dating to approximately 17,000 years ago. Although the figures are nude and lack defined facial features like specimens found in western Europe, the bodies of these eastern works are slim with less prominent sexual characteristics. Some scholars believe the groups living in these regions might have been more stable with fewer anxieties surrounding maintaining the population.

The large number of female figurines and the predominance of female representations over male ones during the Paleolithic highlights the social importance of women in the hunter-gatherer societies of that time. It is remarkable to consider that these female figures, sharing many stylistic traits, were being carved across a broad geographic range of Paleolithic communities—from southern France all the way to Siberia—for at least 20,000 years. The symbolism transcended a particular time and place and was kept alive across all kinds of natural terrain and environments. The archaeological evidence suggests a deep-rooted common ideology in the Paleolithic period about the value of women.

Connections to the past

Learn more

Ice Age Art: Arrival of the Modern Mind. Jill Cook, British Museum Press, 2013.

Prehistoric Art: The Symbolic Journey of Humankind. Randall White, Harry N. Abrams. 2003.