How National Geographic photographed Queen Elizabeth II

Exclusive photos and fond memories from our photographers reveal a rarely seen side of the storied monarch.

Elizabeth Alexandra Mary Windsor sat on an ancient throne, her eyes downcast. Moments before she had been clad in white. Now she was Elizabeth II, Queen of the United Kingdom and its Commonwealth realms—shoulders wrapped in golden cloth, hands clasping jeweled scepters, and head heavy with a crown. Cries of “God save the Queen!” echoed throughout Westminster Abbey as silver trumpets blared.

At the June 1953 coronation, no one could have guessed Queen Elizabeth’s reign would last a record-breaking 70 years. But the significance of the elaborate ceremony was not lost on veteran photographer James Jarché. Using a Leica camera loaded with Kodachrome film, he documented every moment of the age-old ritual, then rushed the undeveloped images to the National Geographic Society’s Washington, D.C., headquarters via special air courier.

The results galvanized National Geographic editors, who dropped other coverage in their September 1953 issue to make room for the stunning color photos, alongside classic Nat Geo takes on everything from the bunting that filled a still war-scarred London to the British-bred silkworms responsible for the queen’s sumptuous regalia.

Letters poured in from around the world, begging for extra copies as keepsakes and gifts. It was “the greatest color story of a lifetime,” photo editor Kip Ross told Jarché.

And what a lifetime. From Elizabeth’s debut as a newly crowned sovereign to the waning days of her reign, National Geographic was there to document the remarkable life of the queen in her role as public figure, as well as to capture rare glimpses of the private life Elizabeth guarded so carefully.

In front of the lens, Queen Elizabeth was gracious, determined, curious, confident. But National Geographic’s photographers can testify that photographing the queen was never a mere matter of point and shoot—and getting the right shot could be as nerve-racking in a palace as in a war zone.

Here’s an exclusive glimpse into what it was like to photograph the queen, from never-before-seen images of Elizabeth to reflections from the Nat Geo photographers who captured her in public and in private over seven decades.

Elizabeth, the photographed

Without the wrangling of a savvy photo editor, National Geographic may never have gotten its shots of the monarch’s grandest moment. Ahead of Elizabeth’s coronation, Kip Ross found out that James Jarché, an “old-time London news photog,” was assigned a choice position inside Westminster Abbey as one of several pool photographers charged with capturing the historic event in images to be shared with publications around the world.

Ross wanted images from the ceremony, but he balked at the fact Jarché would be using an unwieldy 4 x 5 camera favored by news agencies at the time. When he found out that Jarché was a gearhead with a love for newfangled “miniature” photography formats, the editor persuaded him to sneak in a Leica camera and 35mm Kodachrome film just for the magazine. A light meter was thrown in to sweeten the deal for Jarché, who agreed.

It was a bold decision that reflected the constraints and possibilities of both formats. The sheer size of the larger cameras meant more detail. But the fact that they had to be reloaded after each shot meant a photographer might miss a critical moment. “Four-by-five is slow and clumsy,” explains John Edwin Mason, who teaches African history and the history of photography at the University of Virginia. “The Leica is small, light, and fast.”

While other pool photographers fumbled with their 4x5s, Jarché discreetly snapped away for National Geographic, capturing every unscripted gesture and movement with his Leica. In his images, the young queen was gradually overtaken by symbol after symbol—robe, scepter, orb—her attendants literally heaping her with the trappings of a royal dynasty.

“The Leica allowed photographers to become flies on the wall,” Mason says.

But there was a fly in the ointment. As people all over the world scrambled to get their copies of National Geographic’s issue packed with unique photos, Jarché was fired by his Fleet Street employer, Odhams Periodicals, for taking exclusive photographs for another publication without its blessing. As National Geographic editors scrambled to give him freelance opportunities, Jarché embarked on a series of successful lectures throughout England using the photographs. Odhams eventually offered him his job back, but he accepted a post at a competing agency instead, retiring as a Daily Mail photographer in 1959.

'The odds are kind of against you'

It was a bumpy beginning, but it wouldn’t be the last time National Geographic’s photographers trained their sights on the new queen. And while they had to prove their mettle with the palace, they again found ways to work around the strictures of its handlers.

When James L. Stanfield began a six-month story at Windsor Castle, the queen’s longtime weekend getaway, in the late 1970s, he got permission to photograph the royal family. But Elizabeth’s minders wouldn’t allow him to photograph a single person who worked for the crown—the hundreds of staff and attendants who were ever present on the royal grounds and around the royals themselves. If a minder was in a photo, it was unusable … and since the Windsors never went far without a staffer, it made capturing candid shots nearly impossible.

“That’s an almost impossible request for the Geographic,” he says.

Stanfield arrived for his assignment at a time when the palace was particularly camera-shy: In 1976, a tabloid paparazzo had pierced the seemingly impenetrable bubble that surrounded the royal family’s private life when he sold photos of the married Princess Margaret and her lover, Roddy Llewellyn, swimming together off the coast of Mustique, in the Caribbean.

It was a loss of innocence that foreshadowed the chaos that would soon engulf the royal family—and complicated things even for decidedly non-tabloid photojournalists.

“The odds are kind of against you,” says Stanfield. It took months for the photographer to build trust at Windsor, painfully aware that he could smash his credibility with one misstep. “In those days, you hardly missed a breath,” he recalls.

The photographer had to ace everything from eye contact to clothing and prove that despite his ubiquitous presence at the palace, his intentions were pure. It was a painfully slow process but one that gradually gained the queen’s respect.

“[S]he had respect for the way I handled myself,” Stanfield says. “That means a lot—the way you move, how fluid you are, and how attentive you are.”

The photographer’s patience at a wary Windsor Castle paid off. One snowy day, he was ambling down the Long Walk in front of the castle when he saw something unforgettable—the silhouette of Prince Philip driving a four-in-hand carriage.

It was an iconic shot, and despite the presence of a royal employee with Philip, Stanfield decided to ask for forgiveness rather than permission and smashed his shutter release button. When he showed the print to a royal press liaison, however, he was told it could never appear in the pages of National Geographic because it included a palace staffer, notwithstanding the fact that the employee was unidentifiable in the long shot.

But a copy made its way into the hands of the queen, who was so struck with the intimate image of her husband that Stanfield’s royal ban was lifted. “She used it as a Christmas card, and hung it in her dining room,” Stanfield recalls—and the photo served as the cover of the November 1980 issue of National Geographic.

Pomp, circumstance, and anxiety

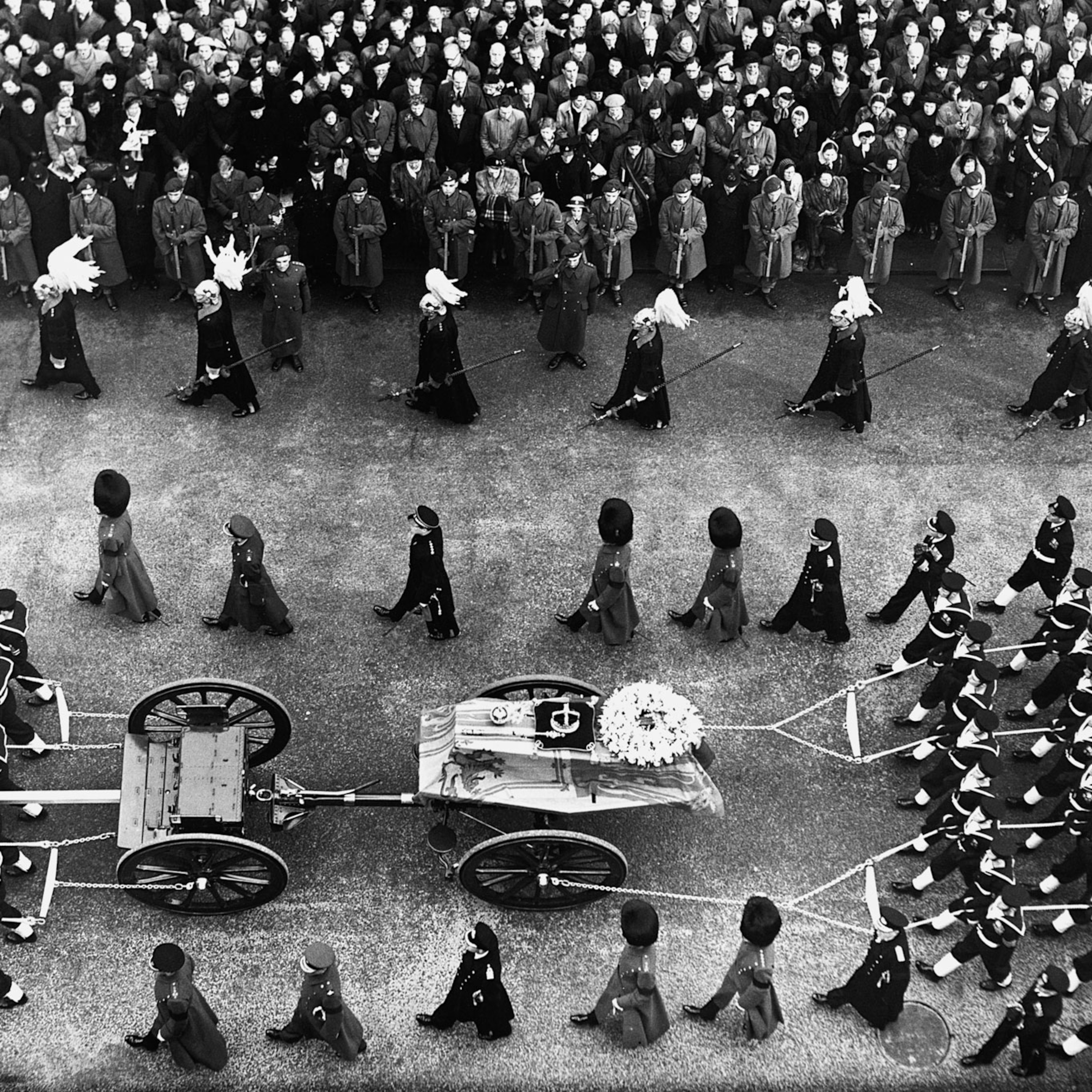

Candid moments were catnip to National Geographic photojournalists, but just as memorable was how the magazine’s cameras lingered over grand configurations of official figures, the brilliant colors of royal buildings, and the spectacle of the United Kingdom’s many age-old ceremonies.

In 1969, a crew of National Geographic photographers captured the queen’s investiture of her son Charles, now King Charles III, as Prince of Wales. During the ceremony at Caernarfon Castle in northwest Wales, Adam Woolfitt watched as the queen, dressed in Easter-egg yellow, placed a glittering coronet on her kneeling son’s head.

The backdrop was clouds and stony castle walls, but the resulting photographs were vibrant. “It was a fantastic setting,” says Woolfitt, who is British. “Lots and lots of pageantry; lots of what we do well.”

“Imagine if the guards had dull gray uniforms,” Woolfitt laughs. “No one would ever photograph them at all.”

But there was the ever present pre-digital anxiety of capturing the right images and making sure that the finicky film arrived at the Society’s Washington photo lab intact.

The magazine’s early reliance on Kodachrome didn’t help. “Kodachrome was a very sensitive film,” says John Edwin Mason. It wasn’t particularly forgiving when it came to exposure, he notes, and since its development process was proprietary, photographers couldn’t correct over- or under-exposed film in the lab.

“When you pressed the button, it was set in stone,” says Woolfitt, who used the film to photograph the queen’s 1961 Opening of Parliament ceremony. “Gives you gray hairs early.”

The three faces of Elizabeth

When National Geographic staff photographer Jodi Cobb went to London in 1984 to photograph “the big ones”—fantastic ceremonies, luscious landscapes, and iconic monuments—for a Nat Geo book on Britain and Ireland, she knew she wanted to photograph the queen. She came away with a sense of the queen’s three public faces.

First, there was the matriarch. “She was the one who held the whole family together,” says Cobb, who captured shots of the queen with her family on the balcony of Buckingham Palace.

Then there was the public figure. As Cobb stood soaking on the dripping roof of the palace, photographing a garden party below, she marveled at the monarch’s sense of duty.

“The Brits are completely unfazed by rain,” she laughs. “Rain is just another manifestation of air.”

So it was for the queen. Even in the crowded party, the petite sovereign was “unmistakable” in a bright chartreuse getup that allowed Cobb to pick her out from afar—and unflagging as she greeted every last guest. “She toughed it out,” Cobb recalls. “She was solid.”

But for Cobb, the monarch’s most striking manifestation was that of the dynastic ruler. During the Trooping of the Colour, the queen’s annual birthday celebration that involves military parades and an inspection of the monarch’s troops, she watched Elizabeth, an expert horsewoman even on sidesaddle.

As she furiously photographed the scene in front of her, Cobb realized she was witnessing the queen expressing her true birthright. “She was a warrior on that horse, the commander of men,” says Cobb. “She was fierce.

“I thought—this is where she really wants to be,” the photographer recalls. “Not shaking hands with hundreds of people. Just … free. She looked like, given the opportunity, she would have bolted for the exit and made a bid for freedom.”

A legacy in photographs

The camera may have loved the vivid colors of royal pageantry and the queen’s always appropriate suits, gowns, and crowns. But National Geographic photographers loved the queen right back.

“When you’d see her, she’d make your heart dance,” Stanfield recalls. “She was just beautiful.” He pauses, his voice thick with emotion. “I mean, she was really beautiful.”

So what does it mean to lose a queen—and with her, a historical figure that bridged the 20th and 21st centuries with so much visual élan?

“Her sense of duty was unwavering for over 90 years,” says Cobb. “She never slid off that pedestal.”

For Stanfield, the queen’s death marks the demise of an endlessly fascinating subject he places at the same level as John F. Kennedy and Pope John Paul II. What does the photographer wish he’d been able to capture during her record-breaking reign?

“Wouldn’t it be great to just spend a night [with the royal family] and see how they let their hair down? Just to be in the rooms and see how they converse with one another—it would be eye-popping,” Stanfield muses. “But no one will ever do that. No one will ever photograph that.”

And no one will ever train a lens on Queen Elizabeth II again.

Woolfitt’s voice cracks as he recalls his subject—the tribute of a photographer who was himself Elizabeth’s loyal subject. “We’ve foolishly fallen out of love with our monarchy,” he says. “The next generation will not be the same. We will have lost something irreplaceable.

“I think this country will go from being Great Britain to being just Britain,” the photographer concludes.