How a teenage girl became queen of England for nine days

The show My Lady Jane took creative liberties, but Jane’s real-life rise and fall were full of drama. Fourth in line at birth, she was unexpectedly crowned queen, only to face a devastating end.

Historic travesty or juicy royal soap? The now canceled series My Lady Jane was both, playing fast and loose with history even as it introduced a new generation to the saga of the doomed Lady Jane Grey, who was England’s queen for just over a week before her execution at age 17.

Who was Lady Jane‚ and why does the story of her disastrous reign still resonate today? Here’s how the teenager became queen and lost the throne in just a few fateful days in 1553.

A struggle for succession

When King Henry VIII died in 1547, his son Edward VI succeeded him at just 9 years old. A regency council ruled in his place until he came of age. Jane Grey, Henry’s niece, was the same age as Edward, her cousin, and had been fourth in line to the throne when she was born. When he was crowned king, she became third in line after Henry’s daughters (Edward’s half-sisters) Mary and Elizabeth.

Council members competed to influence Edward, who was seen as sickly and pliable. By the time Edward and Jane were teenagers, John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, had pushed his way to the top.

As the king’s most trusted advisor, Dudley was arguably the most powerful man in England. He was also destined to become Jane’s father-in-law.

Who was Jane Grey?

The teenager was exceptionally educated for a young woman of her time. Multilingual and accomplished in both academic and domestic pursuits, she was known as pious, studious, and charismatic. But she had no choice as to her future: Like other daughters of nobility, Jane was expected to submit to an arranged marriage designed to consolidate power and bring prestige to her family.

Accordingly, her parents brokered a match to Guildford Dudley, the Duke of Northumberland’s son, and they married in 1553, when she was 16. Though historic accounts differ, Jane is thought to have opposed the match. One chronicle even states that Jane’s father beat her until she agreed to marry.

In the meantime, the King Edward had become gravely ill. As his death approached, the Duke of Northumberland played on fears that if she took the crown, Mary, a Catholic, would destroy the Church of England and that both Mary and Elizabeth might marry outsiders, diluting the power of the British throne. He convinced Edward to exclude them both from the line of succession, instead pushing the Duke’s new daughter-in-law, Jane, to the front of the line for the throne.

Despite quarrels over the legality of this arrangement, Jane was named Edward’s heir—and when the king died on July 6, 1553, Jane became queen.

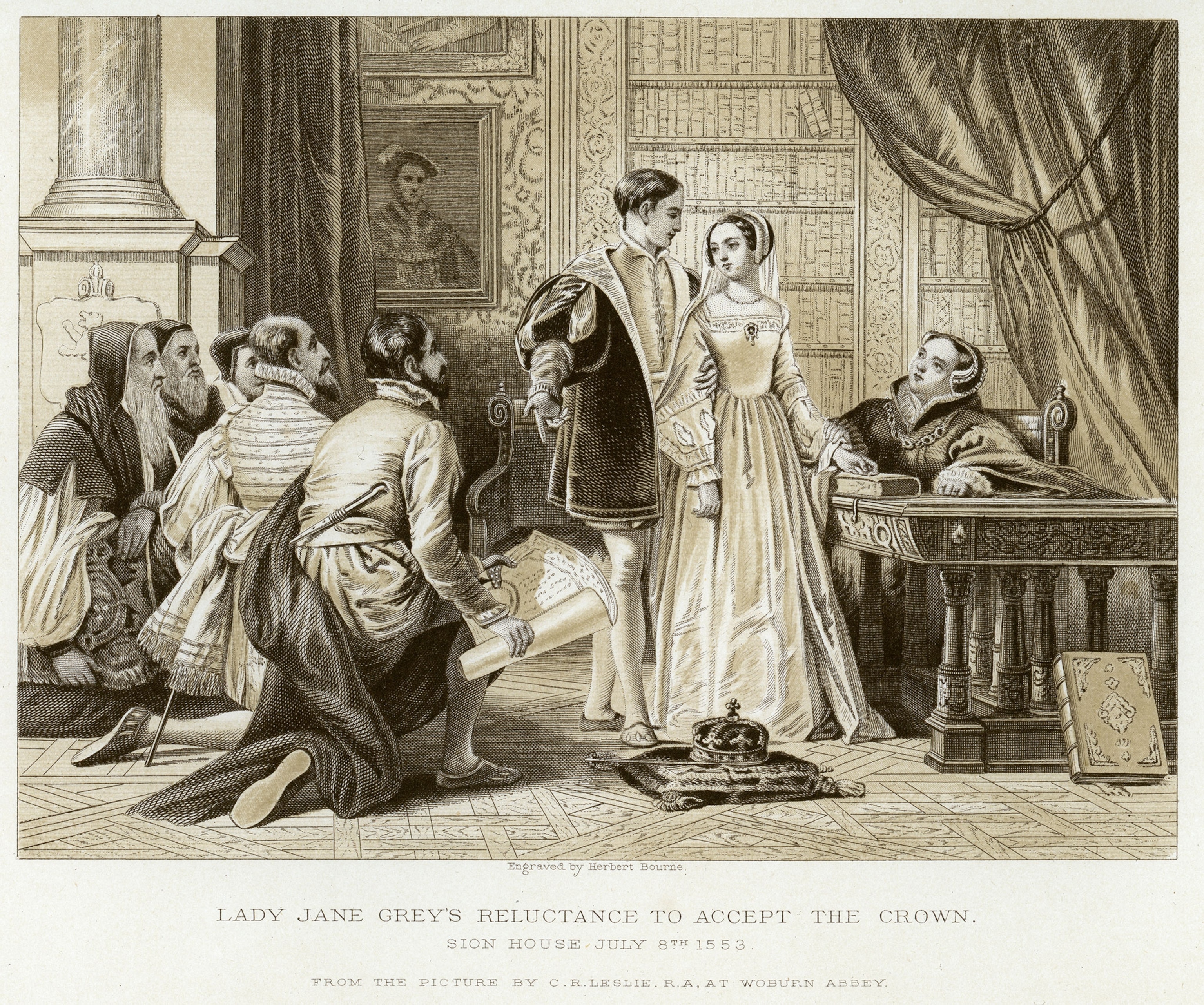

Jane becomes a reluctant queen

This was news to the teenaged Jane, who had apparently not been informed of the arrangements beforehand. As the men around her knelt in obeisance, she later recalled, she “[declared] to them my insufficiency” and “greatly bewailed myself.”

Panicked and shocked, she prepared to move to the Tower of London, where new royals traditionally resided before their official coronation. On July 10, she traveled to the tower on a royal barge.

As the Holy Roman Emperor’s ambassador Jehan Scheyfve ominously noted, “No one present showed any sign of rejoicing, and no one cried: ‘Long live the Queen!’”

The new queen seemed deeply uneasy about her accession—she had to be convinced to don the crown. In a move that appeared to reflect her horror at the Duke’s attempt to gain power through her marriage, Jane refused to allow his son Guildford to be crowned king consort without approval from Parliament. This predictably infuriated the Duke.

Lady Jane becomes a prisoner

Within days, Mary sent an army to London to depose Jane. Though the Duke initially attempted to raise an army on her behalf, Jane’s royal council soon disbanded, leaving the teenage queen and her remaining supporters virtual prisoners inside the Tower of London. Meanwhile, the Mayor of London declared Mary queen.

Finally, Jane’s father came to the tower and told her to stand down, declaring that she “must put off [her] royal robes.” Jane reportedly replied, “I much more willingly put them off than I put them on.”

Just nine days had passed between Jane’s proclamation as queen at the Tower of London and her abandoning her claim to the crown on July 19, 1553. Though she relinquished it easily, Jane was already marked for death.

Mary triumphantly headed to London to take up the throne, and the Duke of Northumberland fled for his life. He was apprehended and brought back to the tower, where he was imprisoned with Guildford and his other sons. He was beheaded for treason soon after, despite hastily converting to Catholicism in a bid to gain favor with Mary.

Jane wrote Mary from prison, narrating the events leading up to her accession, apologizing for taking the crown and begging for her life. The letter portrays her as a pawn in her ambitious parents’ and in-laws’ game, and she writes that she was “stupefied and troubled” by how she was ushered onto the throne.

Jane Grey's execution

Jane seemed to have convinced Mary to spare her life, even after she and Guildford were both tried and found guilty of treason. But the new queen’s patience broke when Jane’s father participated in a short-lived rebellion in opposition to Mary’s planned union with a Spanish king. The ascendant Mary sentenced both Jane and Guildford to death.

Jane might have been able to save herself by converting to Catholicism, but she refused. She also refused to see her husband, whom she had apparently come to love, citing the “misery and pain” that would come with a meeting and telling him they would be forever linked in death.

On February 12, 1554, Jane was killed shortly after her husband’s execution. “I am come hither to die,” she reportedly said to the assembled crowd before the axe fell, confessing her guilt, reading a prayer, and begging the executioner to be quick. Then she was beheaded—a casualty of ambition, greed, and a historic struggle for the throne.