How Tomb Raiders Are Stealing Our History

The illegal antiquities trade is booming, wreaking havoc on the world’s archaeological heritage.

The lady in the striped wig with the staring eyes lies on a brightly lit table as the professor hovers a palm’s breadth from her face. “Still in remarkable condition … extremely well preserved,” the professor murmurs. As her gaze glides down the victim’s body, painted on the lid of her coffin, she points out a fresh cut across the upper thighs, and symbols of the god Amun, an ibis, and magic spells from the Book of the Dead. “And here is her name and title: Shesep-amun-tayesher, Mistress of the House. By reading it aloud, I fulfill her wish to be remembered in the afterlife.”

The Egyptian noblewoman has been dead some 2,600 years. Sarah Parcak, an Egyptologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, is examining her inner sarcophagus, one of three wooden cases that, nested like Russian dolls, once cradled her mummified body, the odor of which lingers in the coffin. Looters sawed this sarcophagus into four pieces and shipped it by airmail to the United States, where an antiques restorer put it back together. Months later customs agents discovered the coffin stashed at the home of a Brooklyn antiquities dealer. It lies in a warehouse at a secret location in New York City, where federal authorities hold seized artifacts from around the world: a huge stone Buddha from India, terra-cotta horsemen from China, reliefs from Iraq, Syria, and Yemen. All are orphans of the illegal antiquities trade, victims of the international battle over cultural heritage.

From murderous temple thieves in India to church pillagers in Bolivia to hundred-man bands of tomb raiders in China’s Liaoning Province, looters are strip-mining our past. Like most illegal activities, looting is hard to quantify. But satellite imagery, police seizures, and witness reports from the field all indicate that the trade in stolen treasures is booming around the world.

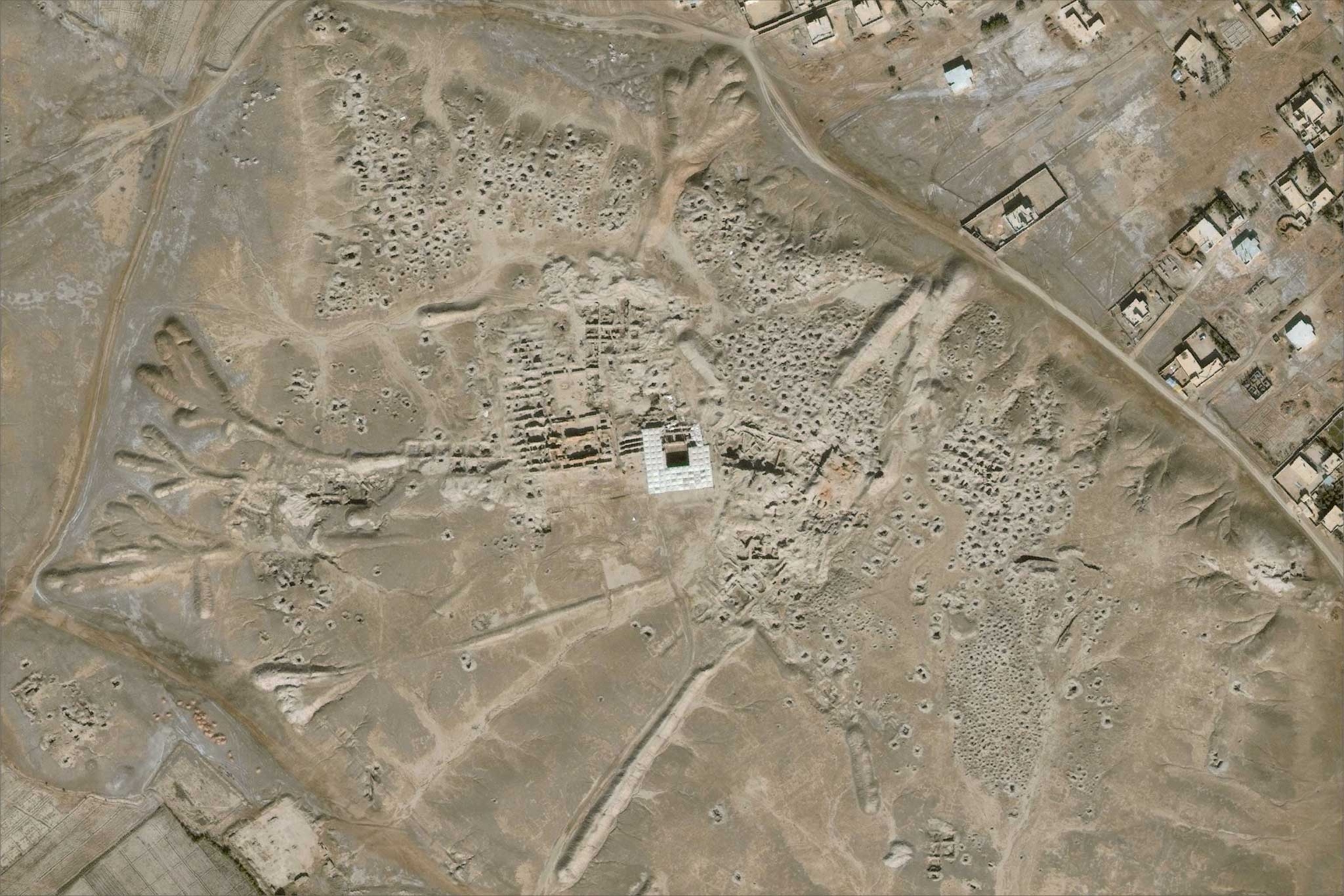

In Egypt, Parcak has pioneered the use of satellite imagery to measure looting and site-encroachment damage. Her research tells a grim tale: A quarter of the country’s 1,100 known archaeological areas have sustained major damage. “At the current rate of destruction, all known sites in Egypt will be seriously compromised by 2040,” she says. “It’s heartbreaking.”

Over the past two decades a series of high-profile court cases and repatriations have exposed the dark side of the antiquities trade, bringing to light criminal networks of diggers and traffickers who sell looted artifacts to Madison Avenue galleries and renowned museums. In 2002 Frederick Schultz, a prominent Manhattan dealer in ancient art, was sentenced to 33 months in federal prison for conspiring to receive stolen Egyptian objects. In 2006 the Metropolitan Museum of Art, under pressure from the Italian government, agreed to return the famous Euphronios krater—a wine-mixing bowl looted from an Etruscan tomb near Rome. And in recent years the drumbeat of war and turmoil in many antiquities-rich countries, culminating in the sack of ancient Mesopotamia by the Islamic State (ISIS), has sparked concern that the antiquities trade is helping fund terrorism.

Yet the debate about how to halt looting has reached an impasse. Archaeologists blame the antiquities trade for looting, claiming that many artifacts on the market were stolen. Collectors, dealers, and many museum curators counter that most antiquities sales are legal. Some argue that the ultimate goal of safeguarding humankind’s artistic heritage obliges them to “rescue” antiquities from unstable countries—even if it means buying from looters.

The story of Shesepamuntayesher gives these abstract questions a harsh clarity. By piecing together clues from Egyptologists, museum curators, and federal agents, I’ll retrace her journey from a grave somewhere in Egypt, through a complex network of antiquities smugglers, handlers, and dealers, to this high-security holding tank in New York City.

The first step is to locate Shesepamuntayesher’s likely burial place. Based on her coffins’ hieroglyphs and artistic style, Egyptologists at the University of Pennsylvania concluded that she lived around 600 B.C. A search of Egyptian coffin books and antiquities websites reveals a similar sarcophagus, of a woman with the same unusual name, reported to have been found at Abu Sir al Malaq, a site 60 miles south of Cairo.

In ancient times Abu Sir al Malaq, then called Busiris, was a prosperous city overlooking the floodplain between the Nile River and El Faiyum oasis. It was famed for its temples of Osiris, god of fertility and the afterlife, and for the splendid graves of its 4,000-year history. Today, in hazy sunlight, Abu Sir looks like a recently bombed battlefield. Craters and shafts gash the rolling sand where looters have rummaged in the earth with shovels, backhoes, and dynamite. In the process they’ve violated countless graves, leaving a grim scree of skulls and shattered bones around many looting pits.

Amal Farag, the head Antiquities Ministry official at Abu Sir and nearby sites, takes me on a tour of the site with five guards carrying Kalashnikovs. A slender, upright woman of 49 with a hard mouth and gentle eyes, Farag picks up strips of cedar with wooden nails and traces of red pigment—fragments of ancient sarcophagi. “The looters keep only the good pieces and smash or throw down the rest,” she says. “For every nice piece, they destroy hundreds.”

Farag leads me to a shaft tomb in a hillside, angling down into a dark chamber. Here, in April 2012, she confronted three looters. During a routine visit to Abu Sir with a colleague, she noticed a taxi parked near the tomb. Coming closer, the two women came face-to-face with three tall, muscular men in galabia robes.

“I told my colleague, ‘If you feel afraid, just pretend you’re very proud,’ ” Farag says. Pride did the trick: After glaring at them wordlessly for a moment, the men climbed into the taxi and drove off.

Now Farag leads me into the tomb and points to the spot on the floor where she found two splendid sarcophagi that the looters had stashed under a blanket. As my eyes adjust to the gloom, I see niches cut in the rock walls of the chamber and tunnels leading to other chambers deeper in the hillside.

Perhaps Shesepamuntayesher was looted from a tomb like this. She would have lain in one of these niches, surrounded by the objects she’d cherished in life: jewelry, a walking stick, papyri containing magic spells, chests decorated with gods of the dead. Her ancestors and descendants would have occupied nearby niches, with their own treasures. If found intact, such a family tomb would open a bright window on the past. Even orphaned by looting as she is, Shesepamuntayesher is valuable because of her hieroglyphs and paintings, but properly excavated she’d be priceless—the difference between a page torn from a book and an entire book, set in a large library.

Farag and her colleague managed to haul the two coffins out of the grave and load them into their car so they could be moved to a safe place. On the drive back to ministry headquarters, they were chased by a Peugeot 504 that came within inches of their bumper. Finally, at an intersection, a truck cut off their pursuers and they escaped.

When we climb out of the tomb, the guards are scanning the neighboring fields and houses, assault rifles ready. Farag explains that local villagers feel no bond with ancient Egyptian culture and pillage their past in order to survive in the present. Poor residents of many archaeologically rich countries think this way, working as low-paid “subsistence diggers.”

Looting increased after the 2011 revolution, when government security forces melted away. But Parcak’s satellite analysis indicates that a major spike had already occurred two years earlier, when the global financial crisis battered the Egyptian economy, driving up food and gas prices and unemployment. Some jobless people turned to looting to survive.

The guards escort us to the highway, and Farag shakes my hand a long time. “Get off the roads by dark,” she says.

This still feels like a revolution.

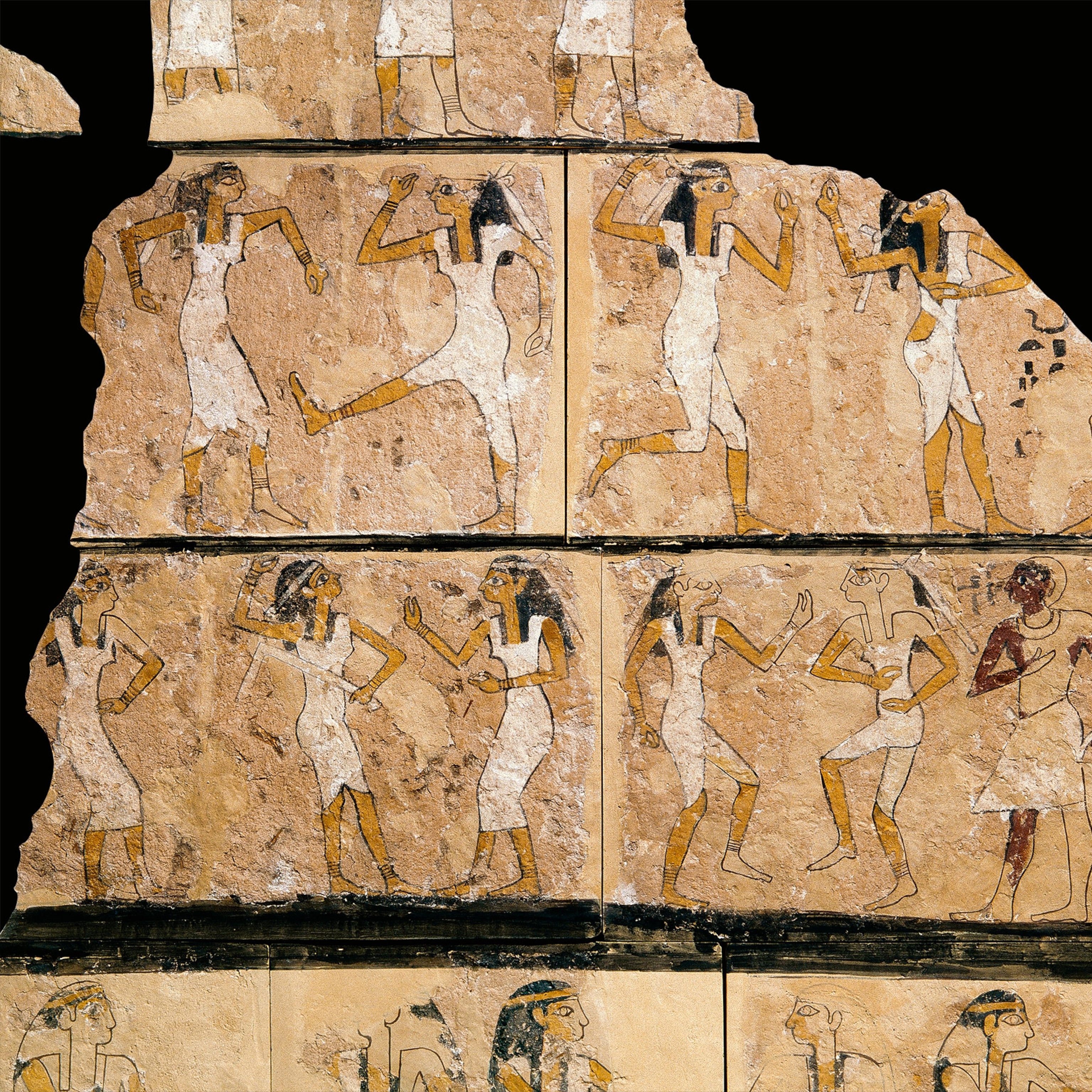

Digging up the past for profit has been a profession for thousands of years. The earliest known trial of looters in Egypt took place in Thebes in 1113 B.C. A gang of looters led by an enterprising quarryman named Amenpanefer pillaged rock-cut tombs. The quarryman and his accomplices were convicted and probably executed by impalement.

Invading armies also have carried off Egypt’s antiquities. Roman conquerors sent entire obelisks back home in purpose-built ships. From the 16th through the mid-20th centuries, when Egypt was dominated by foreign powers, countless pieces of its past were sent to cultural centers abroad by means of gift, trade, and coercion. Foreign archaeologists received a portion of the artifacts found in their excavations through an official arrangement with Egyptian authorities known as partage, from the French for “sharing.” Travelers bought antiquities from licensed dealers in Cairo, Luxor, and elsewhere. Such transactions often went undocumented, because antiquities were widely considered personal possessions. Though laws already existed to protect antiquities, the modern concepts of cultural property—and looting—were still evolving.

Change in Egypt and beyond began in the 1950s, as colonial empires dissolved and former subject countries gained self-rule. Inspired by a new sense of national identity, many countries strengthened existing laws or enacted new ones to protect their past, which included still buried artifacts. In 1983 Egypt declared that all items of cultural significance and over a century old belonged to the state. In 1970 UNESCO adopted the Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export, and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, which to date 131 countries have signed.

Twenty miles north of Abu Sir, I meet Mohammed Youssef, director of the rich Middle Kingdom sites of Lisht and Dahshur. In the chaotic months after the revolution of January 2011, gangs of looters ravaged the sites, sometimes using earthmovers and digging at night under floodlights.

Youssef shows me the rock-cut tomb where, soon after the revolution began, he and one of his inspectors rescued two magnificent limestone reliefs stripped from another tomb. Two groups armed with machine guns were arguing over the reliefs. “When we approached, they shot their guns in the air. They weren’t afraid of us at all,” Youssef remembers. His team returned when the gunmen were gone, however, and recovered the reliefs.

Might makes right in unstable areas, especially in wartime. During the Cambodian civil war, the Khmer Rouge and other military groups often controlled looters working in their territory. Likewise in Syria today, ISIS takes a cut of looting profits, but so do groups affiliated with the armies of President Bashar al Assad, the Kurdish YPG, and the opposition.

Youssef says important locals play a key role in Lisht and Dahshur. “There are very well known people involved in the looting. They are wealthy, prominent, untouchable.” One family in a nearby village, Youssef says, commands a large private militia.

Brig. Gen. Ahmed Abdel Zaher, the short, broad, jovial chief of operations of the Egyptian antiquities police, explains that many looting networks in Egypt are structured like four-tiered pyramids. (“Pyramids, of course!” he chuckles.) The base, perhaps three-quarters of the manpower, is made up of poor villagers whose knowledge of the local terrain and monuments is essential to finding loot. The second tier consists of intermediaries who collect objects from local diggers and organize workers into crews. Third-tier players, Abdel Zaher says, spirit antiquities out of the country and eventually sell them to foreign buyers at the apex of the looting pyramid.

In Egypt, as in other source countries, profit margins rise steadily as artifacts move up the chain. Some second-tier looters have been reported to resell objects at 10 times the price they pay to diggers. “These are professional criminals, and antiquities are just one of the things they deal in,” Abdel Zaher says. He describes several recent drug raids in which police found antiquities alongside narcotics.

In unstable areas, antiquities may follow the same distribution networks used by arms traffickers. “I often found caches of antiquities together with RPGs [rocket-propelled grenades] and other weapons,” says Matthew Bogdanos, a New York prosecutor and Marine Corps colonel who served in Iraq in the early 2000s.

Among the 50-odd ports, airports, and overland routes used to smuggle antiquities out of Egypt, I choose to visit Damietta. Shesepamuntayesher’s coffins were shipped to the United States from Dubai, in one instance hidden in a container loaded with furniture. Damietta is one of Egypt’s busiest containerports, doing a brisk business with Dubai, and is also the country’s furniture capital, where newlyweds go to furnish their first home. Port officials recently seized several shipping containers of furniture with illicit antiquities hidden inside.

It’s only 150 miles from Cairo to Damietta, but the drive takes me nearly five hours. The previous night insurgents had killed two police officers outside my hotel near Cairo, and sporadic RPG attacks have occurred on this road. Security is high, with regular roadblocks. I study the endless stream of trucks that pass them, piled high with onions, melons, caged chickens, and bales of wool. Any of these vehicles could have concealed Shesepamuntayesher’s coffin.

Once Shesepamuntayesher reaches Dubai, her trail finally grows clearer. On the basis of emails, customs declarations, and shipping manifests, prosecutors and federal investigators allege that three men were involved in sending her from Dubai to the United States: Mousa Khouli, a Syrian-born antiquities dealer based in New York City; Salem Alshdaifat, a Jordanian citizen based in Michigan; and Ayman Ramadan, a Jordanian based in Dubai. (Khouli eventually pleaded guilty to smuggling and making false statements to a federal agent and was sentenced to six months’ home confinement. Alshdaifat pleaded guilty to a false official writing misdemeanor and was fined a thousand dollars. Ramadan remains a fugitive.)

Documents produced in litigation show that Alshdaifat sent snapshots of Shesepamuntayesher’s coffin set to Khouli, and Ramadan and other parties eventually shipped the pieces—with misleading descriptions of the contents and value—to Khouli and a coin dealer in Connecticut. Khouli then used the same snapshots to resell the sarcophagi to a collector in Virginia. Investigators with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) allege that Ayman Ramadan handled antiquities looted from Syria, Jordan, and Libya. And emails between Alshdaifat and potential customers suggest his direct knowledge of looting in Egypt.

Brenton Easter, an ICE special agent who investigated the Shesepamuntayesher case, observes that international looting networks collaborate with each other far more successfully than law enforcement officials do with one another. He points out that the container that brought Shesepamuntayesher’s outer sarcophagus to the U.S. was shipped by Amal Star Antiques, a Dubai company. According to Easter, Amal Star is owned by Noor Sham, of the Sham family of antiquities dealers based in Mumbai, India. Investigative journalist Peter Watson, in his book Sotheby’s: The Inside Story, alleged that members of the Sham family ran a major looting and smuggling operation that brought temple sculptures from India into the U.K. in the 1990s, sometimes via Dubai, and consigned several prominent pieces for sale with Sotheby’s in London.

“I don’t always know the good guys around the world, the other law enforcers in different countries,” says Easter, surveying a world map pinned to his cube in the Department of Homeland Security’s headquarters in New York. “But the bad guys all seem to know each other. It’s like they’re on speed dial.” He says that a cooperator from the Middle East recently said that smugglers and dealers in the region are following his work carefully. He nods sharply, pursing his lips. “Guess that means I’ve got their attention. Good. Now I know I’m doing my job.”

Unlike other illicit goods such as drugs or arms, looted antiquities start dirty but end clean (at least in appearance), their illegal origins being laundered as they pass through trafficking networks. Without a detailed provenance—a documented chain of ownership—it’s impossible to know whether an object is fair or foul. Yet even many items that are collected legally lack a solid provenance, creating a dilemma that collectors, dealers, and museum curators face with every potential purchase.

Mousa Khouli sold Shesepamuntayesher to a pharmaceutical entrepreneur and antiquities collector named Joseph Lewis, who lives in Virginia. Lewis was indicted with Khouli and the others in May 2011 on charges that included conspiracy to smuggle and conspiracy to launder money. After nearly three years of intense litigation, he received a deferred prosecution agreement and the eventual dismissal of all charges. Lewis denies all wrongdoing, saying that he purchased the objects in the U.S. from a dealer who handled their importation.

If there is a collecting gene, Joe Lewis has it. His mother collected vinegar cruets, model elephants, and duck decoys, while his father fancied firearms. Lewis himself started bottling ants shortly after he learned to walk. Now his 6,500-square-foot house holds all his mother’s cruets, ducks, and pachyderms, together with his own 30,000-specimen insect collection and an important assemblage of Egyptian antiquities.

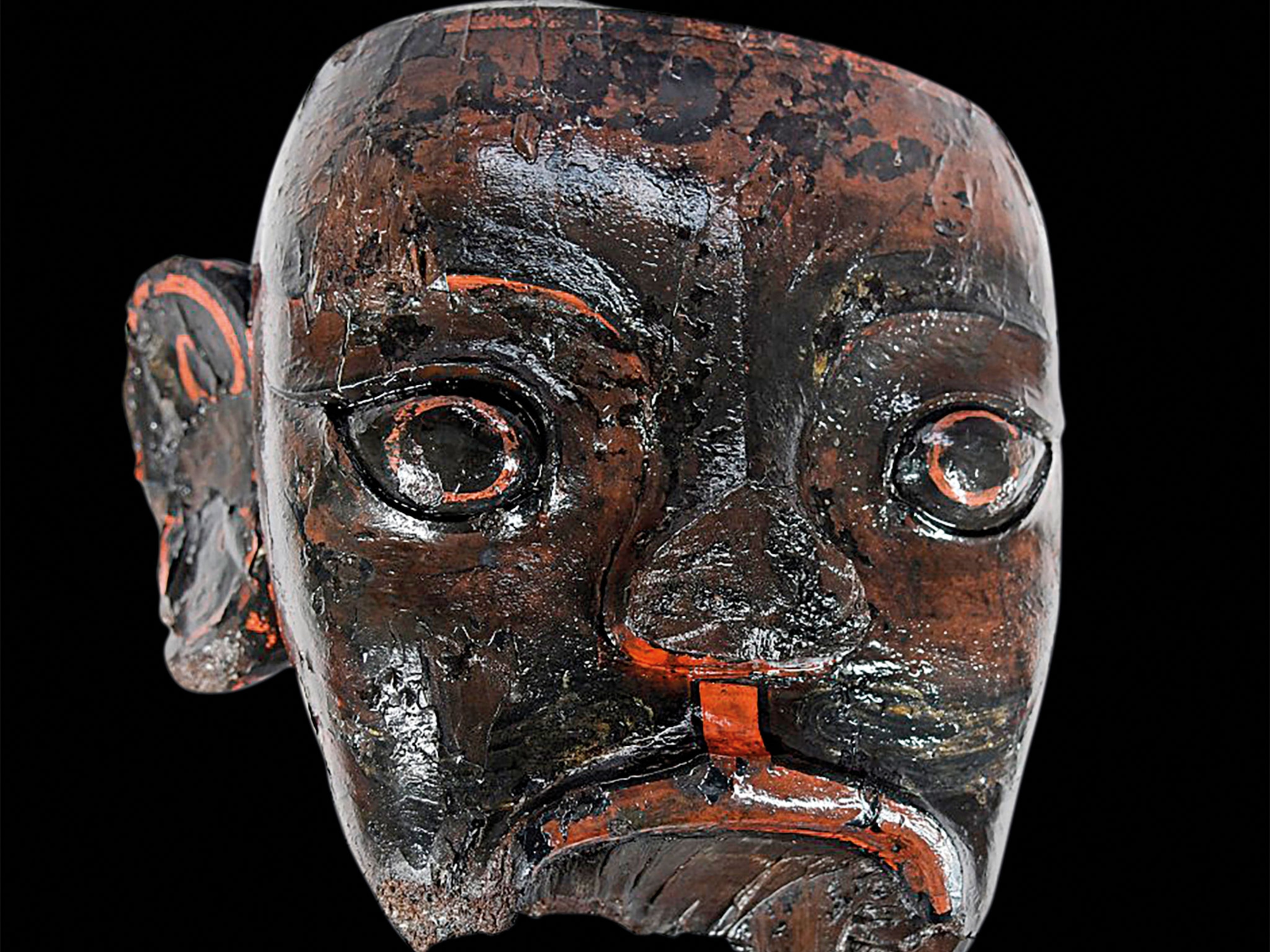

“If you give me two of anything, I’ll start a collection,” says Lewis, a trim, chipper man of 60 whose speaking voice is almost a shout. He shows me cherrywood cases with drawer after drawer of purple-winged grasshoppers, iridescent butterflies, and giant wasps, all pinned out in death. We see his remarkable Egyptian collection, which includes several stunning sarcophagi housed in museum-quality cases complete with climate control.

As we admire a magnificent painted wood statue of Ptah-Sokar-Osiris, with his solemn golden face and mesmeric eyes, I feel the same pull that I’ve felt staring at a few other Egyptian antiquities, the same eerie sense of life stirring just below the surface. I understand the desire to own such an object, to live for a time beneath its calm, infinite gaze. Only a few months earlier I’d felt the same throb of wonder at Sotheby’s while standing before a black diorite bust of a priest from the Temple of Karnak and knowing that, for $500,000, it could be mine.

The future of antiquities collecting is threatened by the steady encroachment of U.S. and foreign laws, Lewis says, so he recently helped form an association to educate and defend collectors. He recites some of their tenets: Collectors, like museums, safeguard the cultural property of humankind, which source countries often fail to protect. Even when an antiquity isn’t excavated by archaeologists, it can retain significant scientific value. Many collectors add to public knowledge by sharing their antiquities with scholars and museums.

Through increased collaboration between the collecting and scholarly communities, a global registry of legitimate archaeological items could be compiled that would be a powerful tool against looting, Lewis believes. “If it ain’t on the list, it can’t be bought or sold,” he says of this hypothetical database. “If it’s not loaded, it’s looted. Done!”

Lewis is hardly the most outspoken advocate for collectors. James Cuno, president and CEO of the J. Paul Getty Trust, says that many recent repatriations have been mistakes, since the mission of encyclopedic museums is to collect, conserve, and share world cultural heritage—and objects returned to conflict areas often are at risk. To this end, he says one shouldn’t rule out buying looted artifacts if doing so would help save them from loss or destruction.

“Would you agree never to negotiate with terrorists, even if negotiating might save hostages?” he asks. “Simply not taking part in a market doesn’t make the market go away. These are not simple, risk-free, black-and-white questions.”

While the antiquities trade may have saved many masterpieces from destruction, the gray areas in which it operates leave it open to accusations that it drives looting—and seems to encourage some of its participants to deceive themselves about where their cherished objects come from.

Lewis says he prefers not to talk about the Shesepamuntayesher case but explains that he bought her set of coffins only after Mousa Khouli, the dealer, supplied a provenance that seemed plausible. (Khouli claimed that Shesepamuntayesher’s coffins came from his own father’s collection.)

Here’s the rub: The UNESCO convention of 1970, patrimony laws, and the court cases and repatriations of the early 2000s all should have made a detailed provenance ever more de rigueur. Yet many collectors, dealers, auctioneers, and museum curators still seem to feel entitled to the same secrecy and anonymity that traditionally have cloaked the antiquities trade. Private sales at the major auction houses are on the rise, and vague provenances like “from a private Swiss collection” or “by inheritance” remain common.

Consider, for example, the statue of the priest that I admired at Sotheby’s. One week before it reached the auction block, Christos Tsirogiannis, a forensic archaeologist at the University of Glasgow, revealed that it was present in the “Schinoussa archive,” a photographic database compiled by a notorious looting and smuggling network. While being in this archive doesn’t prove an object is tainted, the auction house’s failure to mention this chapter in the statue’s provenance raises disturbing questions. (Sotheby’s calls Tsirogiannis’s claims “inaccurate and irresponsible.”)

“Since 2007 I’ve identified numerous objects from these [looters’] archives at nearly every major auction,” Tsirogiannis says. “The fact that the auction houses continue to sell them shows that they don’t really care to improve their behavior. They only care to continue to sell.”

Generic or nonexistent provenances have long been accepted at high-profile auction houses, even for art from looting-ravaged areas or war zones. From the 1970s to 2011, auction houses including Christie’s and Sotheby’s sold masterpieces of Khmer statuary, despite the evident risk that they had been stolen from jungle temples during and after Cambodia’s ferocious civil war. Major museums such as the Metropolitan and the Cleveland Museum of Art also bought or received Khmer statues.

“Those pieces should have raised every red flag in the world—no one could have bought or sold them in good faith,” says Tess Davis, a lawyer and executive director of the Antiquities Coalition, a Washington, D.C., advocacy group. “Just a few years before, collectors had been lamenting the absence of Cambodian art in the U.S. But when a genocidal civil war broke out, magically the market was flooded by masterpieces—unprovenanced masterpieces with evidence of violent theft, sometimes cut off right at the ankles!”

Having followed the Shesepamuntayesher coffins through the criminal supply chain that brought them from Egypt to the United States, it’s hard for me to see buying artifacts that lack ironclad provenance as anything but willful blindness. Archaeologist Ricardo Elia agrees. “This is straightforward,” he says, invoking the basic laws of economics. “You pay money for looted objects, you drive more looting.”

The battle over cultural property continues, but there are signs of hope. In 2010 the Boston Museum of Fine Arts created a new job, “curator for provenance,” the first and only such position in the U.S. In 2013 officials at the Metropolitan Museum voluntarily repatriated two signature Khmer statues, a move later followed by the Cleveland Museum of Art and other U.S. museums. The Met subsequently held a major exhibit on Southeast Asian art, with the cooperation of the Cambodian government.

“This kind of collaborative work, which aims at long-term loans rather than outright acquisitions, is a powerful and positive step for museum curators,” observes Patty Gerstenblith, a professor at DePaul University College of Law who specializes in cultural heritage.

On April 23, 2015, Shesepamuntayesher’s coffin was flown back to Egypt, where it’s now on display in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Meanwhile some museum curators, as well as collectors like Lewis, are calling for an antiquities database to help discourage looting and are proposing to meet with archaeologists in a search for common ground.

Finding this common ground is crucial, in source and consumer countries alike, says Sarah Parcak. Looting is likely to continue until diggers in Egypt and buyers abroad see antiquities not just as gorgeous objects but also as vital passages in the narrative of our past.

“Human history is the greatest story ever told,” Parcak says. “The only way we can understand it fully is if we uncover it together.”

CORRECTION: A caption in an earlier version of this story stated that the pictured basket of artifacts was sold in an antiquarian shop in northwest Syria. The artifacts were sold in an antiquarian dealer's home.

Egyptologist Sarah Parcak, a National Geographic fellow, won the 2016 TED Prize for her work in satellite analysis of looting. She’s using the million-dollar grant to develop an online platform to protect sites.

How can our readers help combat looting? The online platform we’re building will empower anyone with a computer to use satellite imagery to monitor archaeological sites and map looting activity. We plan to launch the site later this year. (For updates see: natgeo.org/space-archaeology.)