The Asian American ‘model minority’ myth masks a history of discrimination

In the 1950s the stereotype that Asian Americans are singularly high achieving arose to drive a wedge between marginalized groups.

If you opened the Seattle Times on February 12, 1970, you might have lingered over John J. Reddin’s nostalgic “Faces of the City” column. That Thursday, Reddin published an ode to the city’s Asian American residents, whom he described as hard-working, well-behaved, and upwardly mobile. “Our Japanese-Americans are among the city’s finest citizens,” Reddin wrote. “Industrious and polite, they have an inherent affection and respect for family and friends...and all of us could take a lesson or two from them in good manners!”

The article outraged Seattle residents like Joseph T. Okimoto, a member of the city’s Asian Coalition for Equality, who criticized the column in a scathing letter to the editor. “On the surface the column appears benign,” he wrote. “But beneath the surface, and not too deep at that, lie certain social attitudes which [betray] a long history of discrimination.” The very characteristics the journalist praised “evolved out of a century of racism against the yellow man in a society which regarded him as inferior,” Okimoto continued.

He was referring to a longstanding stereotype of Asian Americans as a “model minority,” a racial group that somehow rose above prejudice and bias to become one of the United States’ most hardworking and high-achieving demographics. The myth is rooted in the nation’s historic mistreatment of people of Asian descent—and its shadow still looms over Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

The roots of anti-Asian sentiment

Throughout American history, Asian immigrants and their American-born descendants have been simultaneously depended on and reviled by their white counterparts, who exploited their cheap manual labor but stigmatized them as lazy, dirty, immoral, and dangerous.

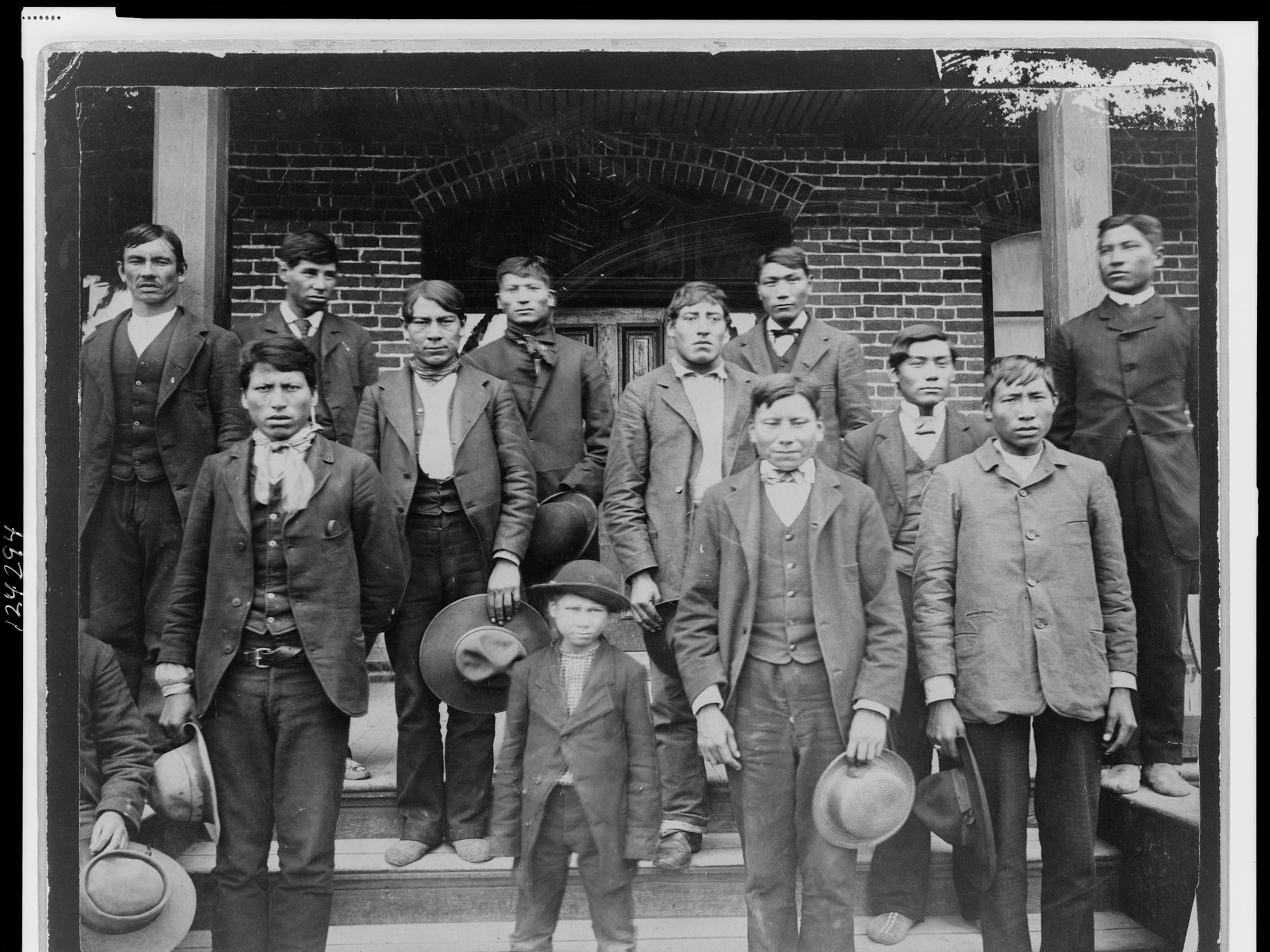

Large-scale Asian immigration began in the 1850s, fueling the national economy and the expansion of the American West. Confined to ethnic enclaves and regarded with suspicion by native-born white Americans and European immigrants, people of Asian descent were soon targeted by the nation’s first restrictive immigration laws. The 1875 Page Act effectively prevented Asian women from entering the country by casting them as prostitutes; the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act put a moratorium on incoming Chinese immigrants that ultimately remained in force until the 1940s. Other Asian immigrants faced laws that restricted naturalization as American citizens to people categorized as “free white” or of African descent.

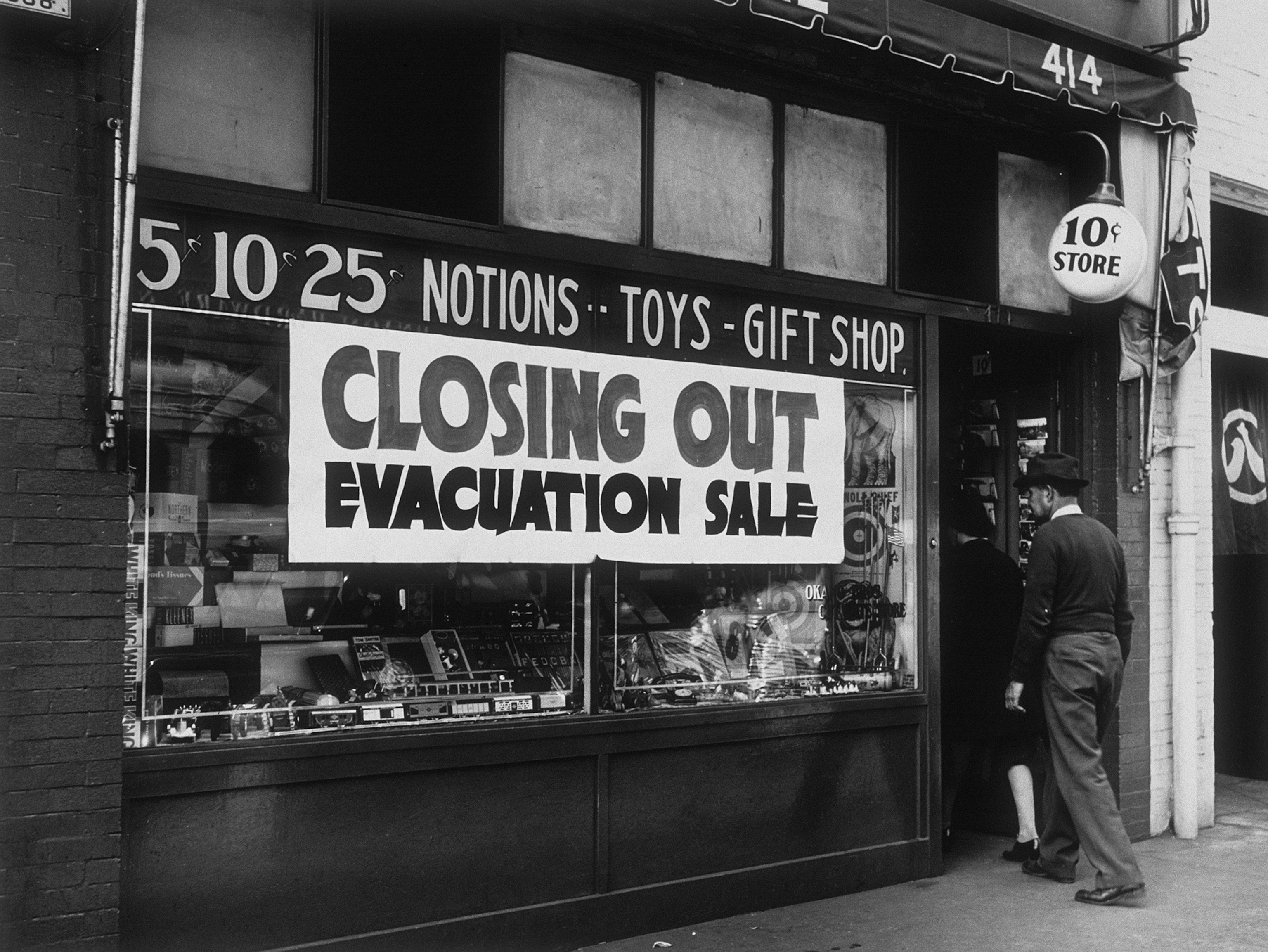

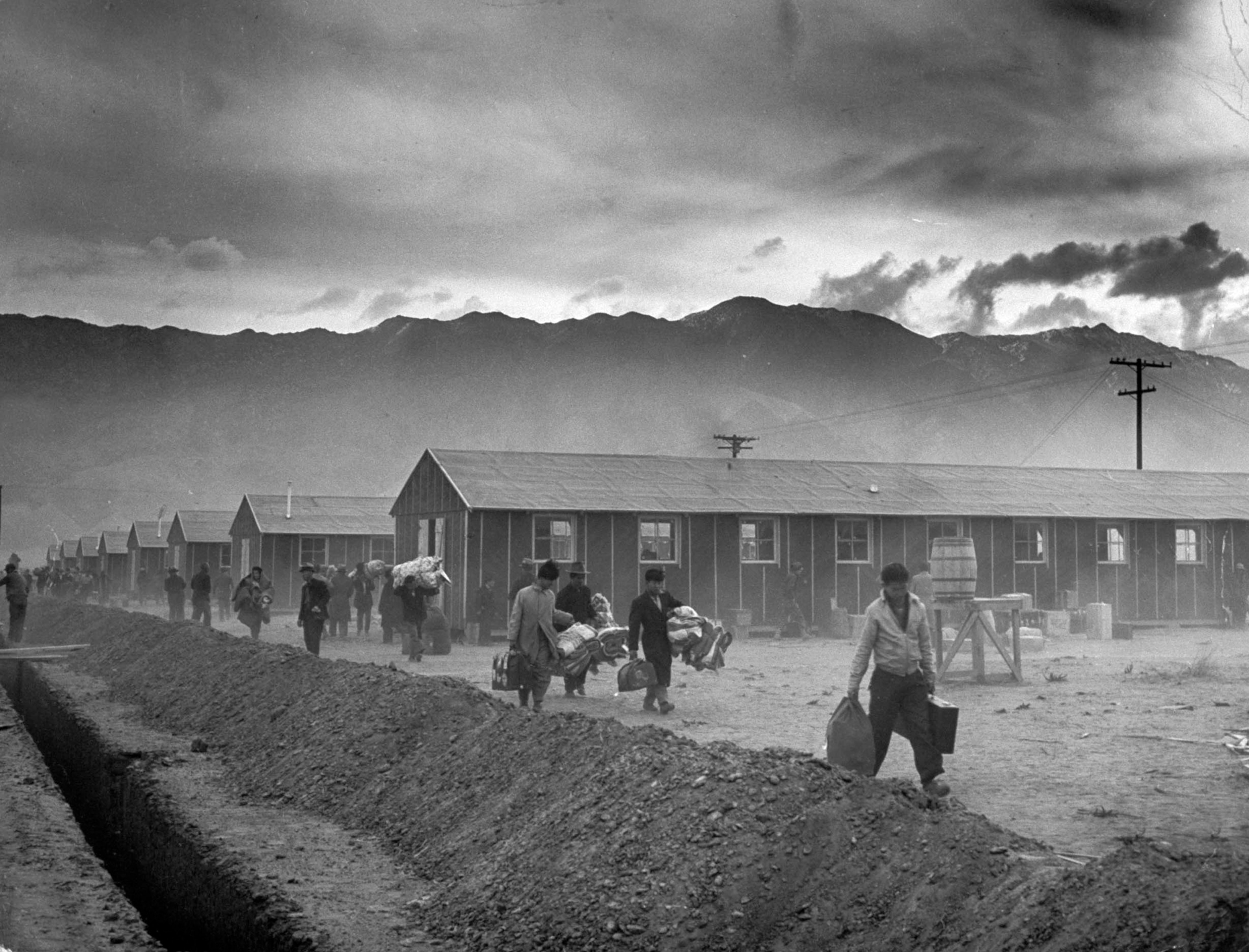

Anti-Asian sentiment continued to simmer, and occasionally overflow, in the early 20th century. By the 1940s, anti-Japanese hostility had grown to a fever pitch. After Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, paranoia that Japanese Americans would betray the United States led the federal government to incarcerate about 120,000 Japanese Americans, many American-born, in internment camps. Forced to leave behind their homes, businesses, and property, many Japanese Americans lost everything.

Recovery—and well-founded anxiety

World War II had decimated Japanese Americans’ fortunes. Ironically, it also marked the end of Asian exclusion as the U.S. sought to shore up its alliances in Asia.

In 1943, the U.S. repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act to counter Japanese wartime propaganda that pointed out American racism in an attempt to erode the country’s alliance with China. After the war, in a gesture of gratitude toward the Japanese Americans who served their country—and hoping to cultivate postwar Japan as a new ally amid rising Cold War tensions—the U.S. granted Japanese immigrants nationalization in 1952. Thirteen years later, in 1965, the Immigration and Naturalization Act provided a pathway for even more Asian immigration, and encouraged both skilled workers and those with family already in the U.S. to come.

But an end to exclusion didn’t ease Asian Americans’ well-founded anxieties about racism and prejudice in the U.S. During the 1950s and 1960s, many Asian Americans, terrified by the xenophobia and disenfranchisement they continued to experience, attempted to keep their heads down and assimilate into white American society.

“By trying to prove we were 100 percent American,” wrote psychologist Amy Iwasaki Mass in 1991, “we hoped to be accepted.” Mass compared the psychological response to the one children develop toward their abusive parents. “We...paid a tremendous psychological price for this acceptance,” she writes.

“Divide and conquer”

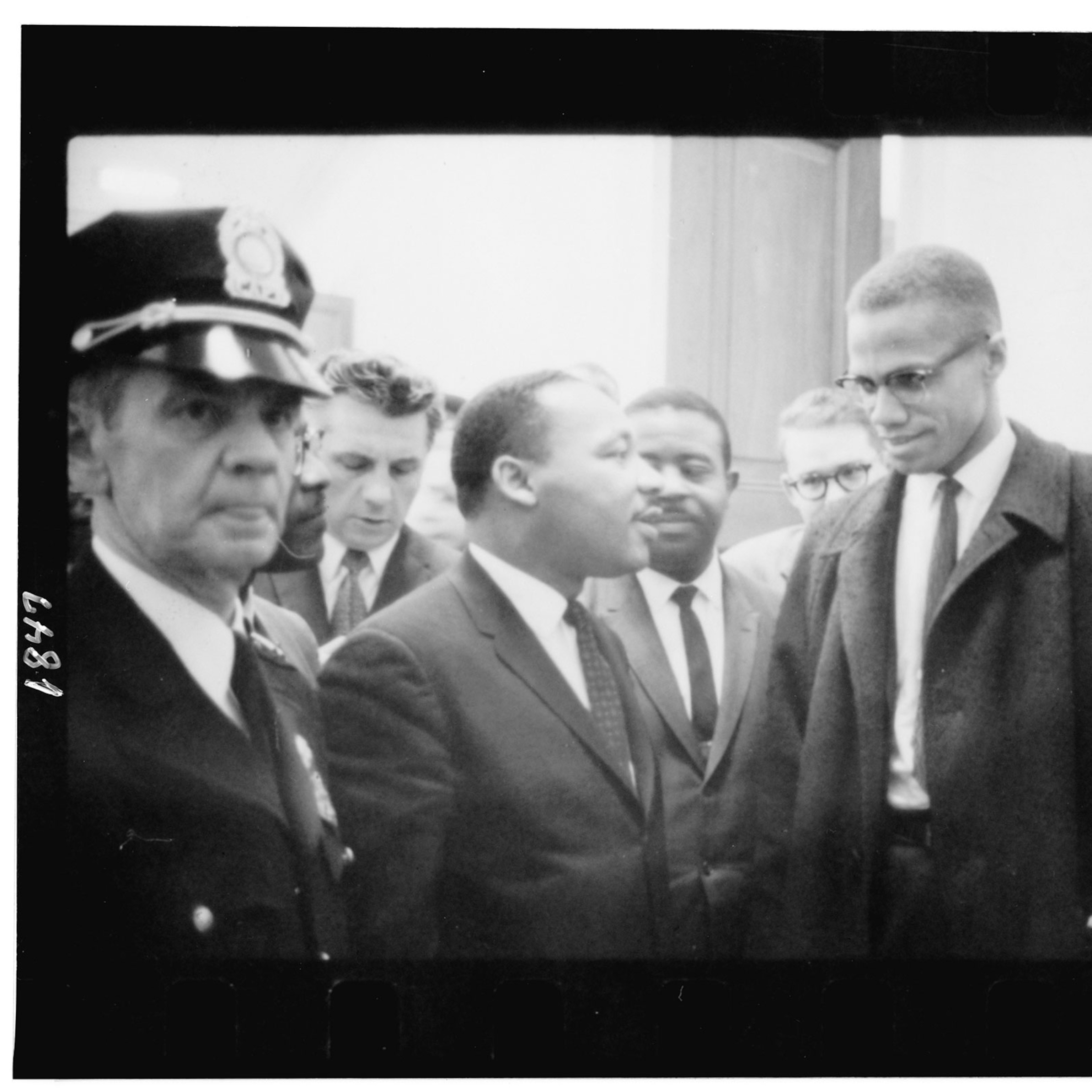

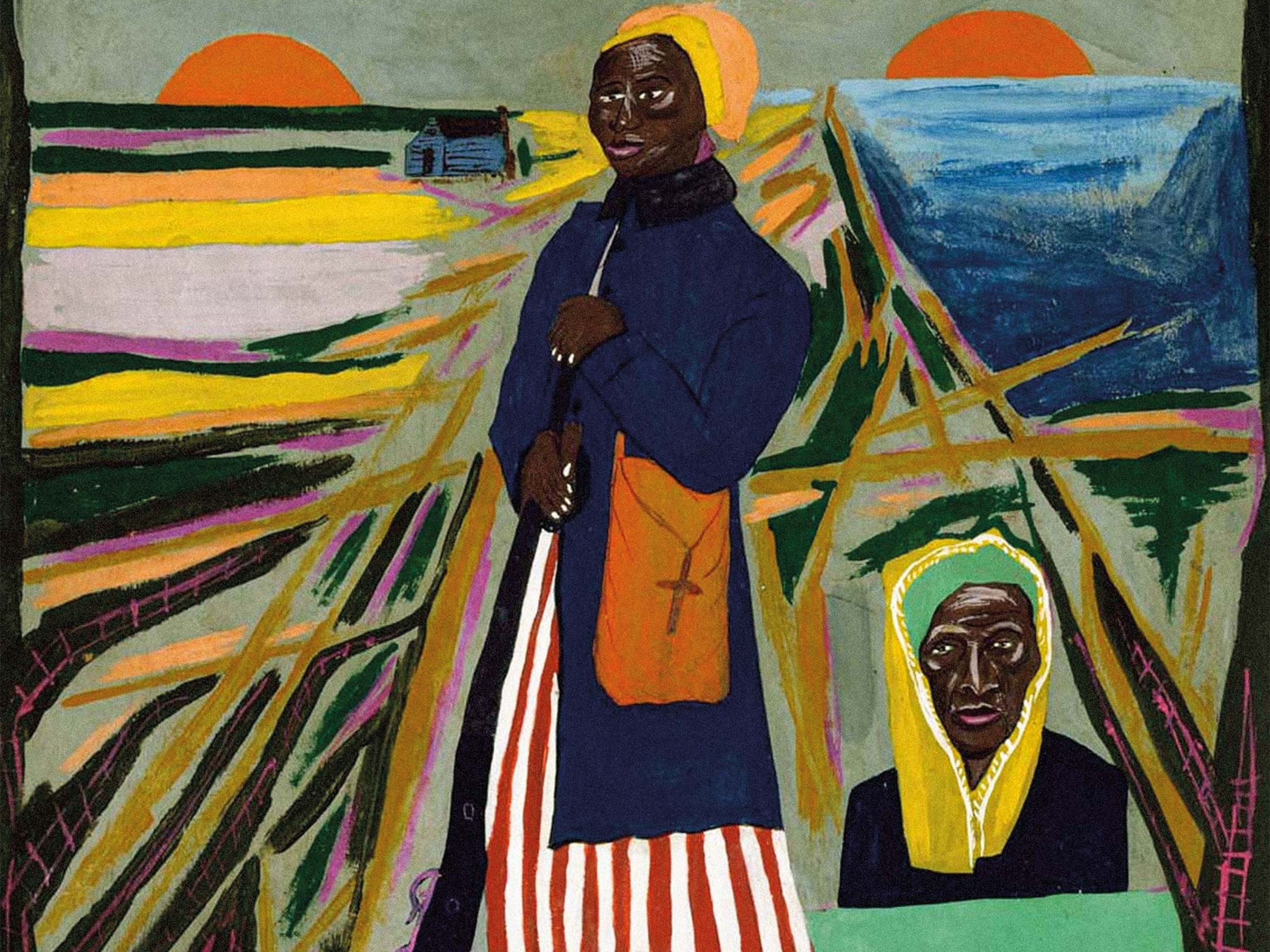

There was another price to pay: A pervasive myth of docile Asian American achievement took root in the 1950s and 1960s. For over a century, Asians had been scapegoated as racial others not worthy of citizenship or equality. But now as the U.S. courted its potential Cold War allies, Asians were lauded as a desirable, hardworking minority—and upheld as a contrast to other groups, such as Latino and Black Americans, who were characterized as a threat to white supremacy.

Japanese Americans, in particular, were singled out as paragons of the American dream. “In spite of being interned by their own government, [Japanese Americans] managed to succeed and become contributing members of society without making a big fuss about being imprisoned against their will,” says Angie Chuang, an associate professor in journalism at the University of Colorado, whose research focuses on race and identity. Though it was fueled by fear, this seeming docility was praised by commentators who were alarmed by other marginalized groups’ growing insistence on their own civil rights.

“This is a minority that has risen above even prejudiced criticism,” wrote sociologist William Petersen in a 1966 article in the New York Times Magazine credited with first articulating the myth. Even better, he wrote, they had achieved all of this “by their own almost totally unaided effort.” Law-abiding, hard-working, well-educated, and even well-dressed, Petersen wrote, Japanese Americans had risen above everything American society had thrown at them. He contrasted them with Black Americans, whom he claimed were “problem minorities” who had rightfully earned some of the prejudices against them.

The reality, though, was that Asian Americans still faced systemic bias and racial discrimination. So did other people of color, says Chuang. “The model minority myth was used as a way to divide and conquer and to use Asian American immigrants against particularly the Black population,” she says. Even as they were celebrated for their hard work, Asian Americans were used as an excuse not to provide social services or meaningful assistance to any marginalized population. And their labor, says Chuang, continued to be devalued by a nation that had long relied on a “compliant” Asian workforce.

Challenging the stereotype

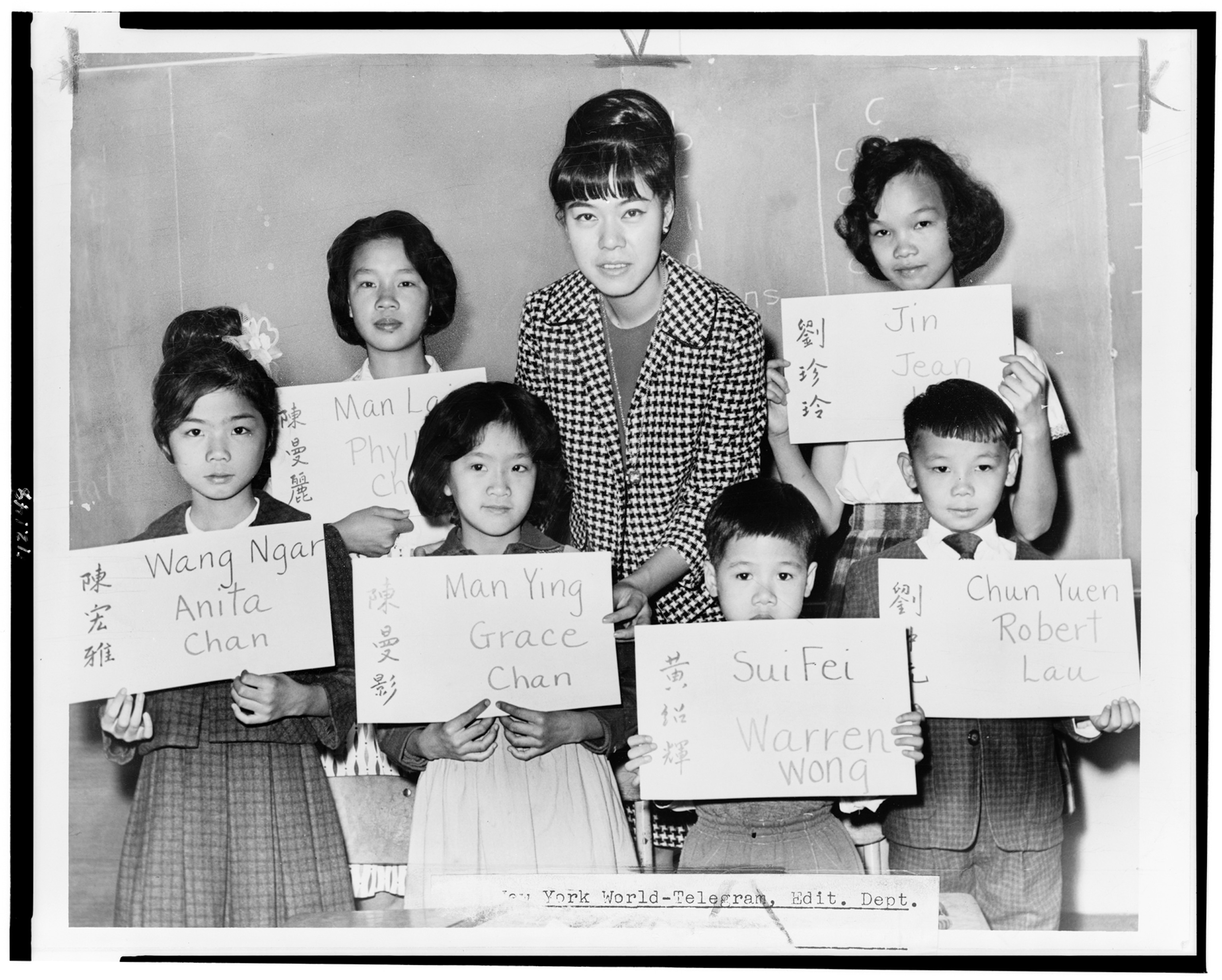

Not everyone bought into the myth, however. The same civil rights movement that galvanized Black and Latino communities in the 1950s and 1960s also energized Asian Americans, particularly those who had seen their immigrant parents struggle against all odds only to be used as a wedge against other groups. Over time, a broad coalition of students, educators, labor activists, and community members seeking redress began to assert a common identity and find pride in the languages, cultural practices, names, and physical attributes they had long been taught to suppress.

Today, the myth’s consequences are better understood. Lumping together Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders—diverse communities that trace their heritage to over 50 countries and approximately twice as many languages and dialects—collapses individual achievements and can mask disparities and discrimination. Though aggregated data can paint a rosy picture of Asian American accomplishment, Christian Edlagan and Kavya Vaghul, policy experts at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, note that there is significant variation in income levels, employment rates, and educational attainment.

The model minority myth “overstates the success of Asian Americans in terms of resiliency, health, wisdom, and wealth,” wrote a group of public health experts from the New York University School of Medicine in a 2016 commentary. They note that since Asian Americans are assumed not to experience disparities, they are not given vital resources. The pressure of supposedly inherent Asian excellence can also have mental health consequences; the myth has been correlated with everything from increased depression and anxiety to higher suicide rates and lower likelihood of seeking mental health services.

Nor has the myth protected Asian Americans from continued bias and discrimination, from microaggressions to anti-Asian violence. Nearly two centuries after large-scale immigration to the United States began, Chuang says it’s time to put an end to the stereotype of people of Asian descent being “quiet or docile or easy to manage. We have to band together and develop a new Asian American Pacific Islander solidarity that didn’t exist before.”