A 'women-only' village? The truth is much more complex—and fascinating

Noiva do Cordeiro in southeast Brazil is a community of tolerance and acceptance. Women have played a major role in shaping it.

If you recognize the name Noiva do Cordeiro, you may know it as the village where everything is dominated by women, the women are all young and beautiful, they regularly send their men into exile, and then the young, beautiful women invite eligible men to …

To a wildly fictionalized version of a real place.

Not one claim in that first paragraph is true about the actual Noiva do Cordeiro, a secluded rural community in southeast Brazil. But the titillating reports have circulated for a decade or more, ever since a few provocative articles were published, replicated by media worldwide, and permanently inscribed on the internet.

For the record: About as many men as women live in Noiva, population roughly 350. Most of the men are away weekly, working in a nearby city. Most of the women work in the village, which residents run communally.

The women (of all ages) take the embellishments with good humor and take pride in the true history of Noiva’s women, one family line especially. In the late 1800s a young woman defied church and society to establish the unconventional settlement. Today a 78-year-old woman—the founder’s granddaughter—leads the thriving, evolving community.

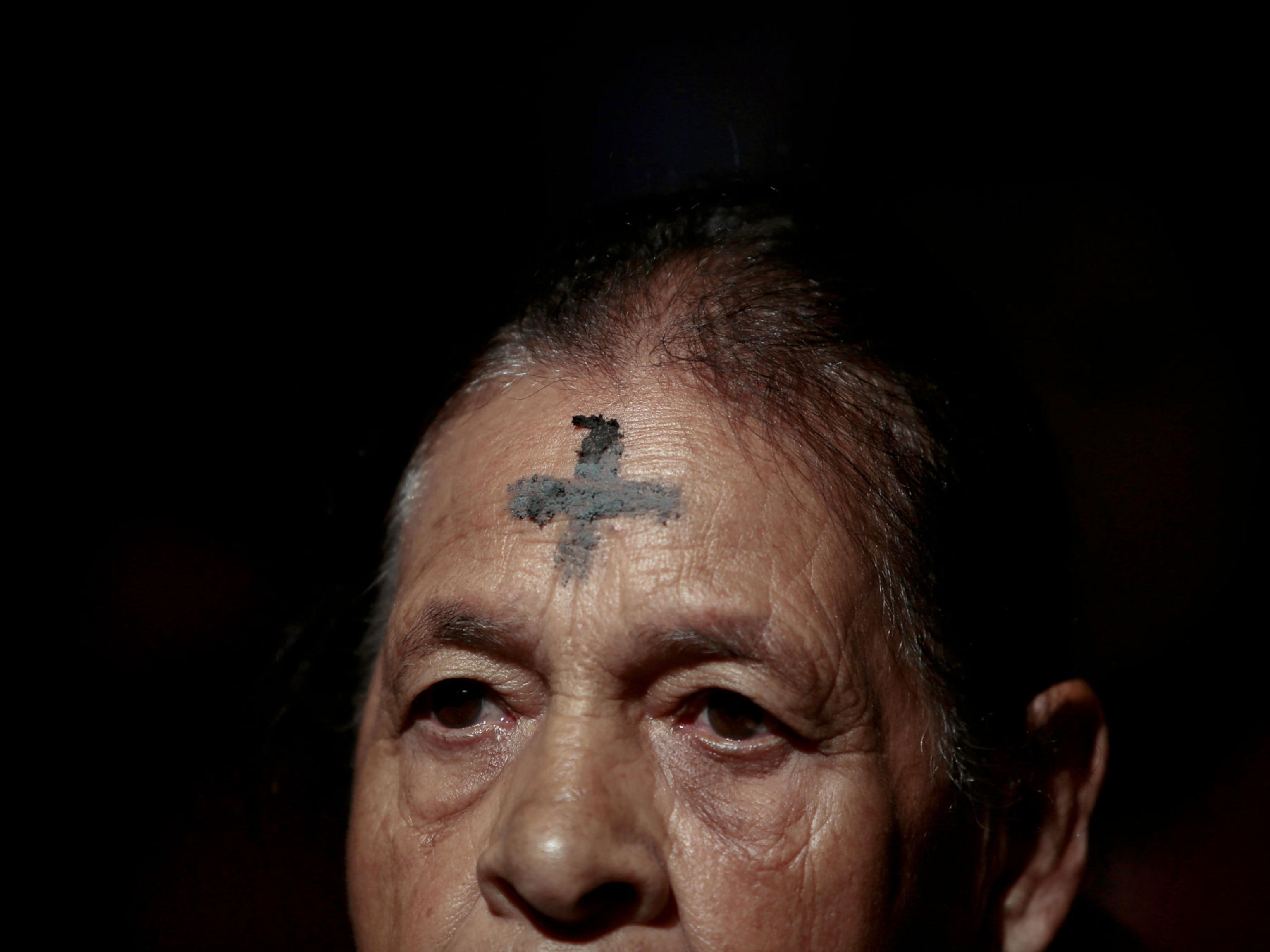

María Senhorinha De Lima came of age in a 19th-century Brazil steeped in Portuguese colonizers’ machismo and Roman Catholicism’s dogma. After three months in a forced marriage, María fled with a man she loved, Chico Fernandes; as punishment, the church excommunicated María and four generations of her descendants. María and Chico settled on land in the state of Minas Gerais. More people joined them, including other women cast out by the church; a community grew, shaped by gender equality and freedom of religion.

(Their identity was forged through resistance: Inside the lives of Brazil’s quilombos.)

But the excommunication haunted the settlement’s families. Women branded “sinners” couldn’t safely leave the village; when children tried to go to school in neighboring towns, they were called “prostitutes’ daughters” and shunned. “It was very sad,” remembers Marcia Fernandes, one of María’s descendants. Still, the village stood for decades as an outpost of tolerance, welcoming the nonconformist, the unrepentant, the outcast.

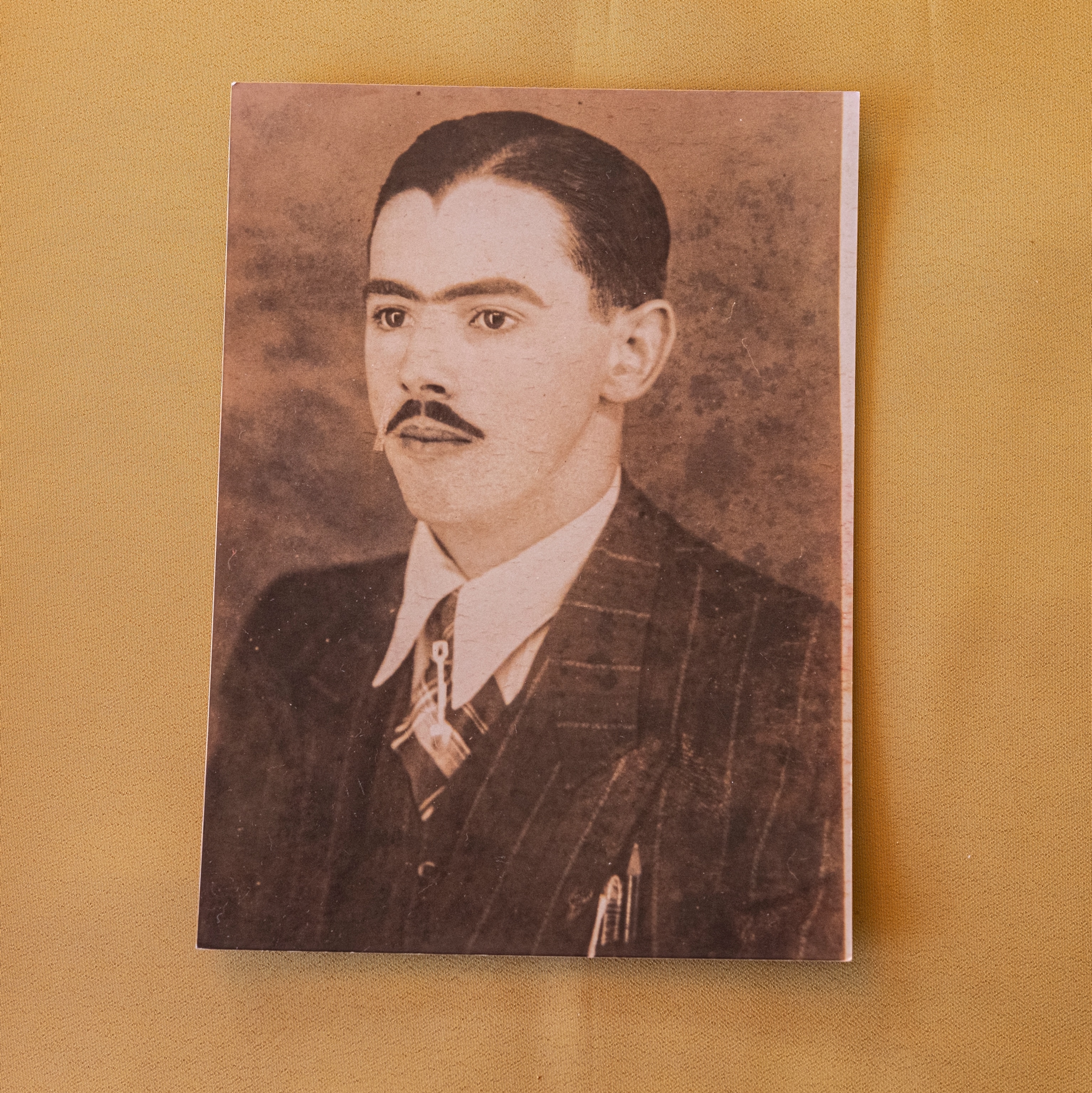

That changed with the arrival in the 1940s of Anisio Pereira, a Protestant evangelist who based his version of Christianity on a literal reading of Scripture. He started a church and offered salvation to onetime Catholics who obeyed him; he restricted alcohol and music, and ordered that women be subordinate to men in all things. As his dominance rose in the 1960s, the 45-year-old preacher took a 16-year-old wife: Delina Fernandes, a granddaughter of María.

“It was harsh, very hard,” says María Doraci de Almeida, 75, who lived under the Pereira leadership. “We women had no say. You could not take contraceptives or have a cesarean section. Delina had her children at home, 15 children, without a midwife. On one occasion, she had her daughter at five in the morning, and two hours later she was already cleaning a pig in the slaughterhouse.”

Pereira named his church with a tender religious metaphor: Bride of the Lamb, Noiva do Cordeiro. But Rosalee Fernandes Pereira, 58, Delina’s third daughter, says now that her father was “very fanatical.” His teachings, she says, were not “the ones that were going to take us to the kingdom of God.” Yet he was never deposed from leadership.

When Pereira died in 1995, his church was closed and demolished. The village retained Noiva do Cordeiro as its name—but to cement the change in lifestyle, one of Pereira’s sons later opened a tavern across the street.

Delina rose to lead the community. Her approach empowered village women yet didn’t seem to upset village men.

“The women here are hard workers. We value them. They are strong; they are examples to follow,” says Marcos Fernandes, who, with his brother Eduardo, takes care of the village’s chickens. “Senhora Delina, for example, is our greatest influence. I can’t imagine life without her. Her presence is so strong that I feel it without seeing her.”

Delina is widely credited with making Noiva once again an inclusive community. In response to growing poverty at the end of the 1990s, she proposed that everything in the village be shared, including the work required for harvesting. “We didn’t have anything; what else could we do?” she says.

The residents bought a large parcel of land near Noiva, where they cultivate 3,500 mexerica (mandarin) trees and seemingly endless rows of coffee plants, the community’s main commercial crops. They also tend to a vegetable garden and communally owned farm animals. Many homeowners have their own vegetable gardens too, from which they contribute to the community pot. Villagers are assigned duties such as fetching firewood, sewing, and cleaning the shared spaces.

“It worked,” Delina says with pride. “We have neither wealth nor money, but we have abundance.” Today she spends much of her time in the village’s central Mother House, sitting in the kitchen, sipping coffee and cutting cabbage to be fed to the chickens. There she also listens to residents who come to her with their troubles and dispenses advice.

Several years ago, a young man named Erick Araújo Vieira returned to Noiva. He’d grown up there and moved away at age 18 to attend university in the state’s capital, Belo Horizonte. When he came home, he went to see Delina and told her he was gay. At the time there were no openly gay men in Noiva. He feared rejection, she says. “He came crying to tell me that he knew it was a sin, that he would not go to heaven. I told him to get that out of his head.”

Delina suggested to her daughters Keila and Marcia that they produce a play addressing questions about sexual identity and orientation. The play helped generate discussion and acceptance in the community. Vieira’s parents spurned him at first, but their relationship later improved, helped by the more open attitudes of others in the village. “When he came with a boyfriend, the elders understood it,” says Marcia. “He kind of paved the way for the others, like my son, who came out afterward.”

Community performances are now held every Saturday. They range from comedies and shows based on current events to a Lady Gaga-inspired musical act that’s earned attention beyond the village, performing in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

Though Rio is barely a six-hour drive away, villagers are seemingly so content that most express no desire to leave their home. Noiva feels like a refuge from life’s toxic ways, where collaboration is preferred to competition and discord gives way to harmony.

Why not play along with the joke? Many in Noiva did when visiting journalists wrote that it was a village with few men, ruled by Amazon-like females, and where milk and honey flowed. Headlines such as “Lost Village of Brazilian Women Appeals for Single Men” attracted suitors from around the world, and film crews sought to recruit Noiva women for reality-TV shows.

“When the reporters came, I used to send the men away” to maintain the fiction that only women lived in Noiva, matriarch Delina jokes. Her daughter Marcia laughs and adds, “With that story of gringos coming to look for wives, the men here felt threatened and they all got married. Even the ones who were dragging their feet.”

Delina’s daughter Rosalee sees a point behind the media hype. To outsiders, Noiva women may appear to dominate the men—but in reality, “what happens is that here there is true equality,” she says. “In the rest of the world, there is not.

“Here we are human beings. It is so simple that it is hard to explain.”

This story appears in the June 2023 issue of National Geographic magazine.