Can your cholesterol drop too low?

Drugs can now drive blood cholesterol levels lower than ever. But how low is too low?

Someone in the United States dies from heart disease every 33 seconds. It remains the number one killer in the country. So it’s no wonder that scientists are increasingly focused on ways to further reduce the bad blood cholesterol, called low-density-lipoprotein (LDL), at the center of the condition. The quest has led to increasingly powerful medicines that plunge LDL to new lows, leading some people to wonder whether there’s a health risk to dropping levels too far.

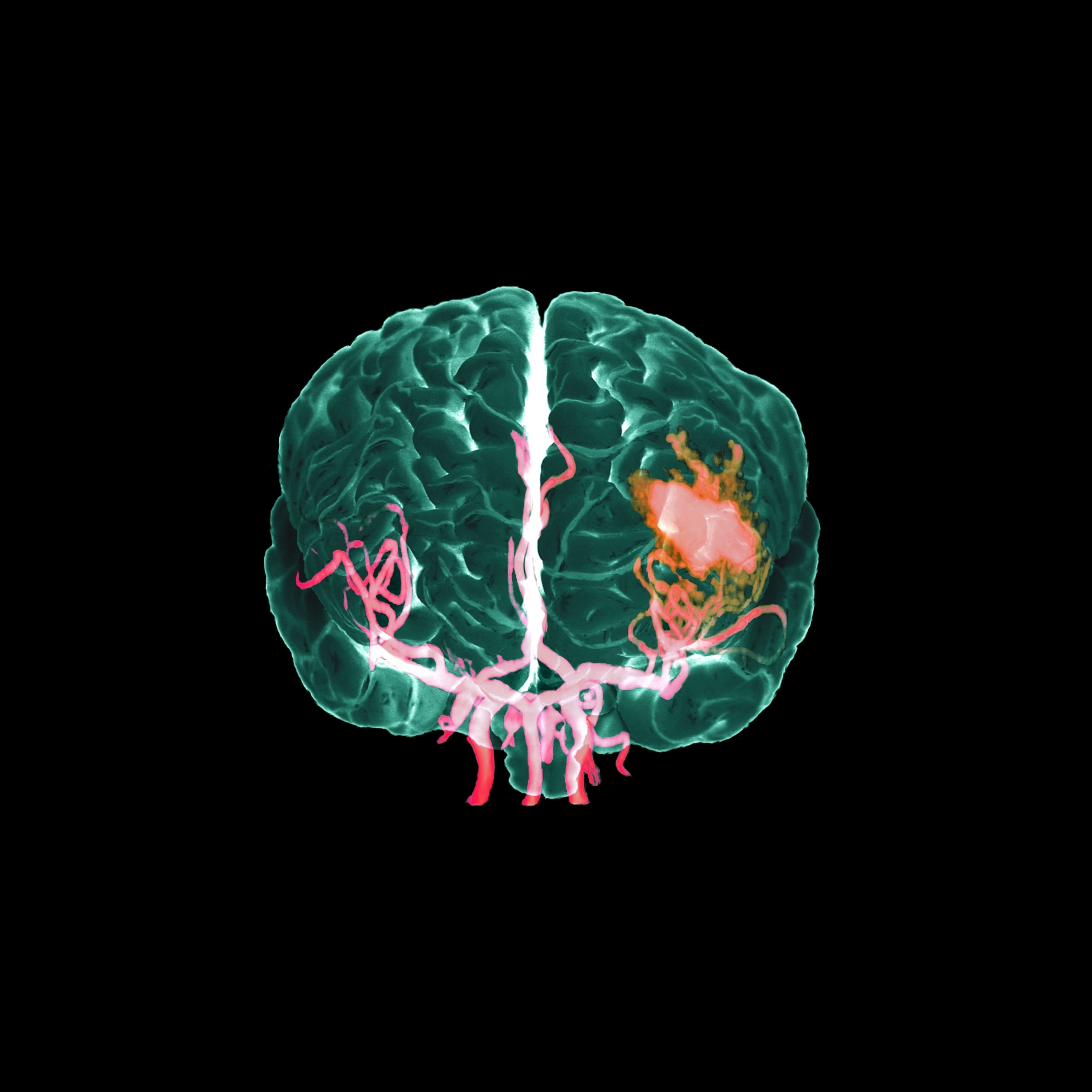

LDL particles are the prime factor behind the buildup of fatty plaque in arteries that can rupture, triggering a heart attack or stroke. “We have a paradigm in cardiology that the lower the better,” says Erica Spatz, a cardiologist at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut. “The question has always been, is there a bottom?” The query has taken on added significance as more powerful treatments are widely prescribed and even stronger ones are in the pipeline, including advanced biologic therapies and gene editing.

Based on a huge body of evidence, people at risk of cardiovascular disease who are prescribed cholesterol-lowering drugs, including high intensity therapies, can feel assured it is a sound strategy, says Donald Lloyd-Jones, a cardiologist at Northwestern University. Lloyd-Jones was a member of the American Heart Association (AHA) committee that released the latest guidelines on cholesterol therapy in 2018 (an update is expected in 2026), as well as the group’s past president.

“We haven’t found a level that’s ‘too low’ yet,” he say. “I like low. Low is what we’re trying to achieve here.”

Statins were first, but stronger drugs have followed

Medical efforts to reduce LDL began in earnest after the first statin drug, lovastatin, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1987. Statins inhibit a key liver enzyme that would otherwise cause the body to manufacture more cholesterol, thereby reducing the amount circulating in the blood. Some 92 million Americans were on statins as of 2019 (the latest year with available figures).

(From cholesterol to nutrition, here’s how your diet may increase your cancer odds.)

Over the years, nearly two dozen randomized, controlled clinical trials have evaluated statin drugs, along with other studies involving hundreds of thousands of people. In 2022, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force concluded that the drugs are linked to fewer heart attacks, strokes, and all-cause mortality.

Current AHA guidelines call for healthy Americans to bring LDL below 100 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL) of blood, while those who’ve had a heart attack or stroke are encouraged to drop LDL at least 50 percent below their current level, to 70mg/dL or, ideally, lower.

In some cases, highly potent statins are needed to reach these marks. In the past decade, injectable medicines have been added to the arsenal; these drop LDL more dramatically. The newer drugs target a molecule called proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9, or PCSK9. These PCSK9 inhibitor drugs turbocharge the liver’s ability to break down and eliminate LDL.

“With those medicines we can get to very low LDL cholesterol levels, below 30 and even below 20 mg/dL,” Spatz says.

A study of evolocumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets PCSK9, found that when people with cardiovascular disease added the drug to their statin regimen, their LDL dropped by 59 percent after two years and their risk of heart attack, stroke, or cardiovascular death fell by 20 percent.

Although longer-term data are still needed, PCSK9 inhibitors are safe, Lloyd-Jones says. “We haven’t seen any concerning issues arising,” he says, which he attributes to their targeted approach. “They're designed to only be able to attack that one protein,” which doesn’t serve any beneficial purposes, he says.

Research is reassuring on memory and more

Still, some patients have concerns about low cholesterol levels. Some stem from epidemiological studies reported decades ago hinting at possible health issues, especially regarding mental health and memory.

Rigorous research over many years has debunked those as myths, says Laurence Sperling, a preventive cardiologist and founder of the Emory Center for Heart Disease Prevention in Atlanta, who reviewed the evidence for the European Heart Journal.

“There is no substantial data to support a relationship between low cholesterol and depression and anxiety,” he says. There’s also no clear evidence low cholesterol causes memory problems or cognitive decline. “The pool of cholesterol circulating in our blood vessels is very different [from the] pool of cholesterol circulating in tissues like the brain,” he says. If anything, since cardiovascular health is crucial for the entire body, lower LDL rates “likely will translate to better brain health,” he says.

The AHA released a scientific statement in 2023 reiterating that “the preponderance of observational studies and data from randomized trials do not support” an increased risk for cognitive impairment or dementia.

Scientists point to situations where LDL cholesterol is naturally low to support the notion that dramatically decreased levels do not harm health. Last year, researchers argued in an editorial in the journal Circulation that LDL levels in newborn babies generally range from 20 to 40 mg/dL, “suggesting that higher levels seen in adults are not essential for cellular processes.” And some adults are born with genes that keep cholesterol levels in the basement throughout their life, with no adverse consequences and healthier hearts, they noted.

Cancer was another potential area of concern after slightly higher rates appeared in a 1996 study in people taking statins to lower cholesterol. But subsequent research hasn’t seen the same trend. In 27 randomized trials tracking people for a median of five years, “statin therapy had no effect on” the rate of cases or deaths from cancer, an analysis by a collaboration of cholesterol experts concluded.

A unique diabetes case and side effects

One risk factor that has persisted has to do with diabetes. In a small number of people who are not diabetic but who have higher than optimal levels of blood glucose or genes predisposing them to diabetes, cholesterol-lowering statins can increase their risk of developing the disease, a review published in Acta Diabetologica in 2023 concludes.

“This does not happen to people with normal blood sugars,” Lloyd-Jones says. And those with prediabetes are themselves at higher risk of heart disease and “need a statin even more.” (You can determine your own 10-year heart disease risk from the AHA’s PREVENT calculator.)

Of course, like all drugs, cholesterol lowering medicines can have side effects. Some PCSK9 inhibitors, for example, cause upper respiratory infections, back pain, and localized reaction at the injection site. Statins have their own mild side effects. Many people link muscle pain to these drugs, but those links are murky. A 2019 study actually found that pain rates are similar among statin-takers and placebo groups.

Who should be on cholesterol drugs?

According to the AHA guidelines, most adults with high LDL levels (at or above 190 mg/dL) or those with diagnosed cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or other risk factors should use statin therapy, while those at especially high risk—meaning they have a history of multiple cardiac events, say, or multiple high-risk conditions—should talk to their doctor about adding the more powerful non-statin drugs.

Of course, even people on cholesterol-lowering medication should improve the lifestyle factors known to protect against heart disease. The AHA guidelines recommend regular exercise along with diet changes: more vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, and low-fat protein sources, and less sugar and saturated fat (especially red meat).

“Lifestyle can absolutely undermine... the effectiveness of drug therapy,” Lloyd-Jones says, pointing to several of his patients with well-controlled LDL from drug therapy whose rates rose dramatically when they started regularly consuming highly saturated oils.

(Nuts are surprisingly great for your health. But which are the best?)

Currently, many people who could benefit from cholesterol medications are not on them. Rates are especially low for Black and Hispanic people, and those without health insurance, according to an analysis tracking millions of Americans. (PCSK9 inhibitors are especially costly.) Women whose cholesterol levels are high are also often undertreated.

“I’m not aware of any other disease process that has had so much time, effort and resources thrown at it, including the number of people in clinical trials,” Lloyd-Jones says. From all this research, people can feel confident that “these are remarkably safe and incredibly effective drugs.”