How uncharted caves in Greenland could predict the Earth's future

An intrepid scientist and her team were the first to venture into the Wulff Land caves—and they found surprising evidence of Greenland’s prehistoric past.

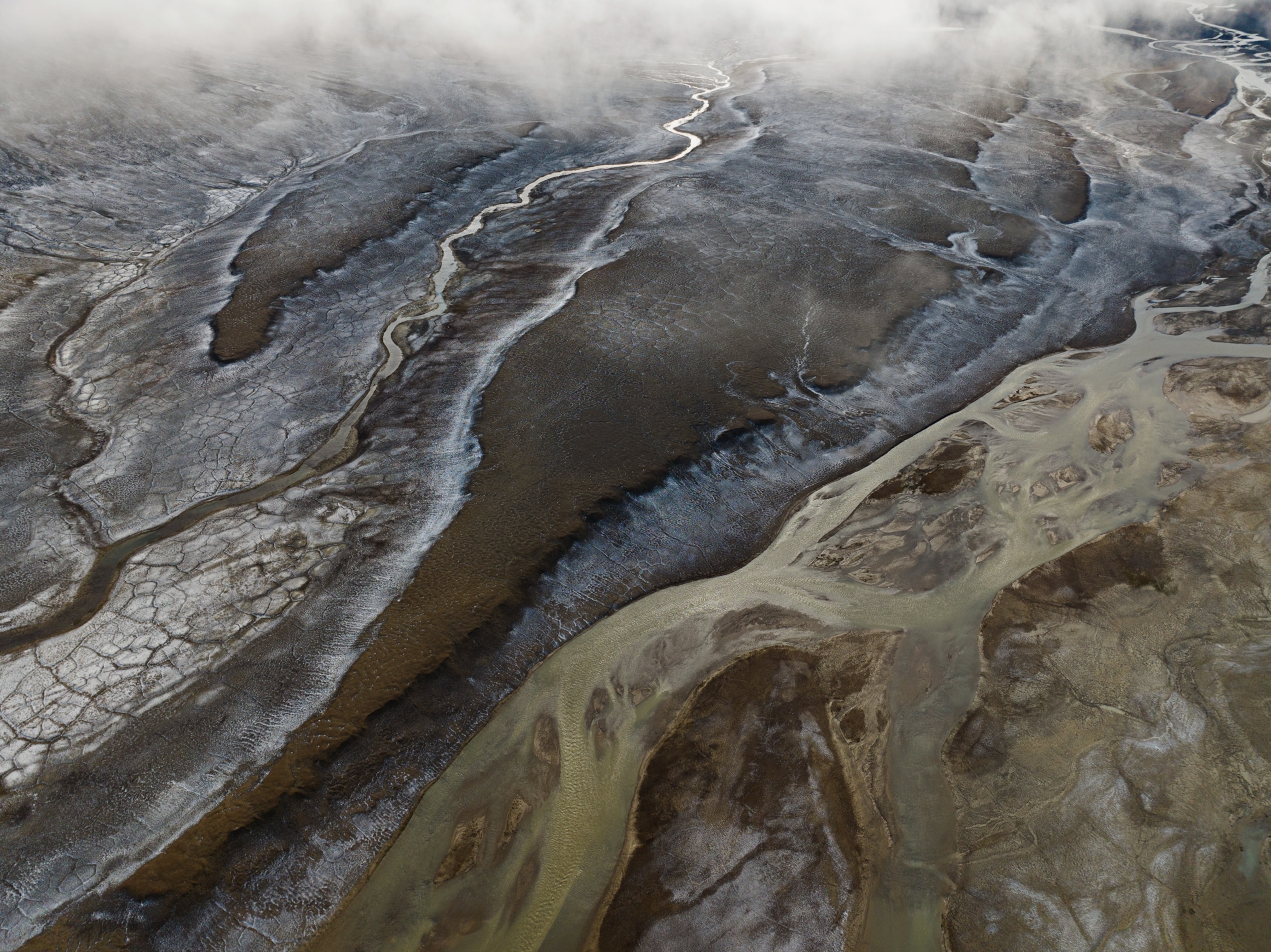

The helicopter landed on top of the cliff, its blades chopping the cold air. Stepping out, National Geographic Explorer Gina Moseley breathed deeply and took in the commanding view of Greenland’s barren landscape. To the south, a frozen lake stretched out for miles, eventually giving way to brown and gray plateaus, interrupted by the white flash of glaciers in the distance. In the other direction, some 560 miles beyond the horizon, was the North Pole. The only other human presence was the helicopter pilot and the other passengers: Moseley’s life partner and this story’s photographer and fellow National Geographic Explorer, Robbie Shone, and technical climbing specialist Chris Blakeley. The weather was mild, just above freezing—perfect, actually—but Moseley knew that storms could blow up at a moment’s notice, bringing dangerous winds and dense fog. In such a case, they’d have to leave immediately or risk being stranded in one of the world’s most remote and forbidding environments. They were poised on the edge separating potential disaster and sublime discovery.

For more than a decade, Moseley—a British paleoclimatologist and caver—had envisioned this moment, hoping to be part of the first team to set foot inside the Wulff Land Cave (WUL-8), one of the most isolated caves on Earth. She dreamed of collecting samples that would open a new window into Greenland’s climate history.

She’d first glimpsed the cave in a grainy Cold War–era reconnaissance photo, its gaping entrance set high in a sheer rock wall resembling an ancient fortress. The picture had instantly captured her imagination. But what had planted the hook firmly in her imagination was the knowledge that no one had been able to set foot inside it. For 15 years, she’d obsessed over the same questions: How big was it? How deep did it go? What scientific treasures did it hold?

Moseley had a bold plan: to explore the Wulff Land Cave (and others like it) and bring back rock specimens from inside. These mineral deposits could reveal what Greenland’s climate was like hundreds of thousands—or even millions—of years ago. But more than a window into the past, these samples might help scientists predict what future warming in the world might look like.

She’d run various gauntlets to get here—logistical, financial, professional, emotional—but now all that remained was to rappel toward the mouth and see what no human had ever seen. After the helicopter flew off, a deep silence fell, and Blakeley began rigging ropes as the others prepared their gear.

(The last flower at the top of the world—and the perilous journey to reach it.)

Many years before she’d ever heard of the Greenland cave, Moseley had fallen in love with subterranean worlds. She was 12, on a family camping trip in Somerset, England, when her mother took her to explore her first cave. “I absolutely loved it from the very first moment,” she says. She remembers walking through a forest and “just disappearing underground and away from the world above.” As a teenager, she would save the money she earned from delivering newspapers after school so she could spend it on summer caving adventures. “Every cave has its own personality,” Moseley says. “Every cave is different. Some are wet. Some are dry. Some are deep. Some are shallow. Some vertical, some horizontal. And so, every experience is different. It’s new every time.”

Eventually, her love of caves led her to a doctorate in paleoclimate science at the University of Bristol. During her undergraduate studies she had discovered that, in addition to being fun to explore, caves are time capsules containing data about past climatic conditions in the form of mineral deposits accumulated over thousands of years. These deposits are formed as water drips into the cave or flows through it, leaving behind tiny amounts of minerals that accrete over time to grow into stalactites, stalagmites, and sheetlike flowstones. Collectively known as speleothems, these structures provide an archival record of the region’s past climate, each layer of deposited mineral having captured information about the temperature from the time of its creation.

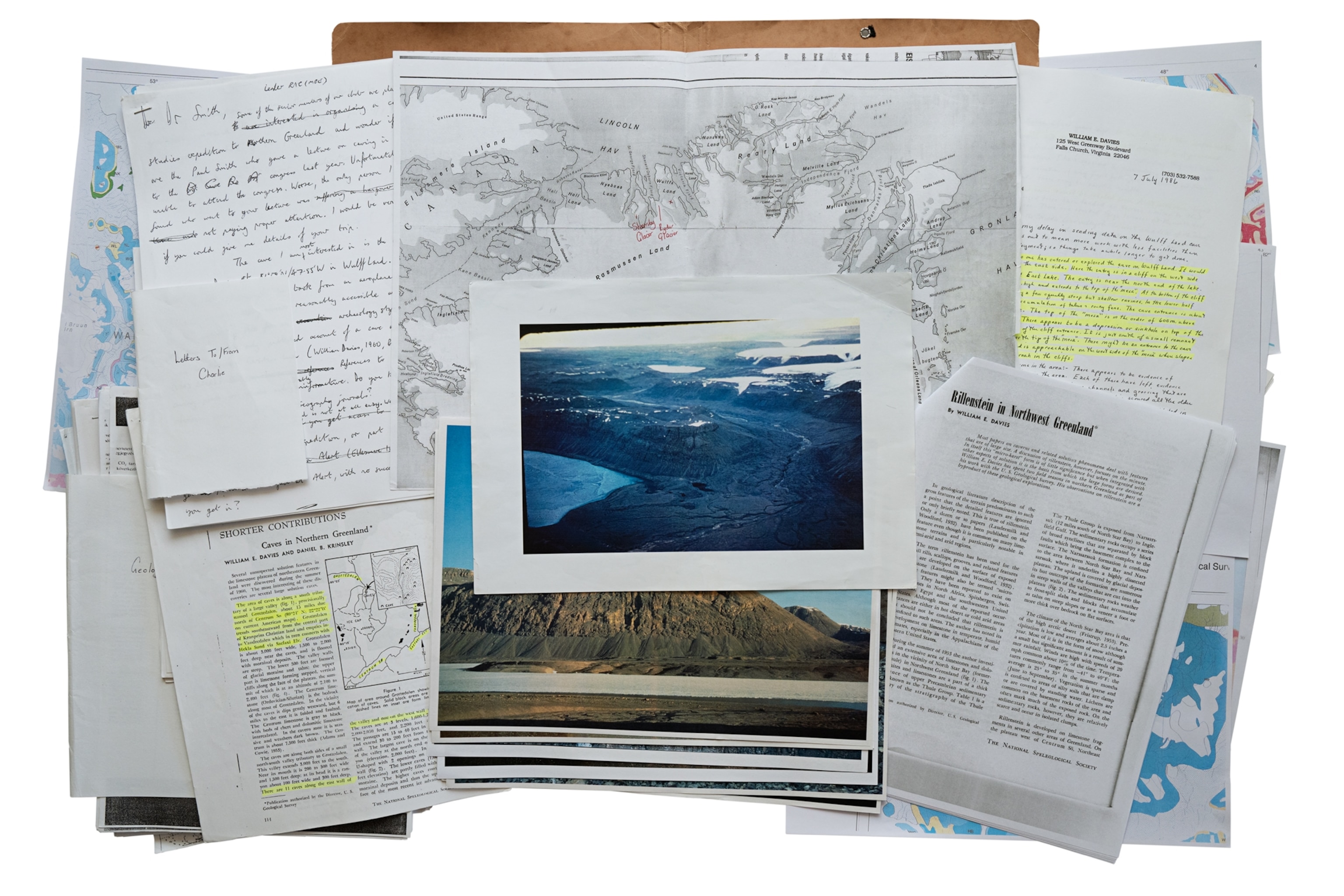

One evening in 2008, at a gathering of the university’s caving society at a local pub, Moseley ran into Charlie Self. A lifelong caver and speleologist, Self told her about a site in Greenland that he’d desperately wanted to visit: the Wulff Land Cave. It was photographed in 1958 by two American geologists flying a reconnaissance plane over northern Greenland.

In the geologists’ grainy image, the entrance appeared to be quite large, and there was no telling how deep it went. Moseley knew some mountain caves could contain miles of passageways. But given the Wulff Land Cave’s isolated cliff-face location, no one had ever explored it.

Moseley was hooked, like a child to a fable. “I just kind of lit up because I couldn’t even imagine that there were caves in Greenland,” she says. A few days later, Self handed her a folder that contained the geologists’ reports, maps, and other information he’d collected over the years as he tried to solve the logistical challenges of launching an expedition. The optimal time a trip could be attempted was during a brief summer window, but the closest landing strip was about 30 miles away, over treacherous mountain terrain offering little shelter. And in the region, named after the 19th-century Swedish explorer Thorild Wulff, the weather was highly unpredictable, threatening to trap a team for potentially weeks on end.

Moseley made photocopies and stuck the papers in a drawer, but she couldn’t put them out of her mind. “I kept the whole thing very secret,” Moseley says. “I didn’t go around telling people in my discipline. I thought if I spoke too soon, I might lose it.”

Earlier that year, on a university caving trip to Crete, she found herself in a group led by Robbie Shone, who was there with the Sheffield University Speleological Society. While the others struggled to find new caves, Shone and Moseley’s team had great success. One shaft gave way to another, cave after cave. In the evening, they’d return to base camp, completely thrilled. “Most of the others were sunburned because they’d spent the whole day on the surface,” Shone recalls. “And we’d be telling them great tales of the big caves that we’d found.”

Their shared love of caves proved to be the starting point for a romantic relationship a year later. It wasn’t until several months after they became a couple that Moseley finally pulled out her Greenland folder and placed it on the table in front of Shone. He was intrigued. By this time, he’d worked as an assistant to photographers on some ambitious caving adventures—including exploring large underground river systems in Papua New Guinea—and understood what it took to execute a high-stakes expedition. But the Wulff Land Cave was something else. “I always thought that it’s just crazy—it’s just too big a project to pull off,” he recalls.

Scientists are eager to learn about climate history because it holds clues to the planet’s future. Earth has experienced extreme changes in climate throughout its existence, seesawing between two fundamentally different states, one hot and one cold—referred to as greenhouse and icehouse Earth, respectively. Scientists agree that there were probably four major icehouse periods (times in Earth’s history with permanent large-scale ice cover) before the one that began about 2.6 million years ago and continues today. Within any icehouse period, there are relatively colder and warmer times, when glaciers advance or retreat, known as glacial and interglacial periods. Before the last glacial period ended about 11,500 years ago, much of North America and continental Europe was covered in ice.

“We want to understand these past climates better,” says Christo Buizert, a climatologist at Oregon State University. “How does the ocean interact with the atmosphere on these long timescales? How sensitive are the ice sheets to temperature change? If we add an X amount of carbon dioxide, how much warming would we see globally?”

Greenland and Antarctica hold special places in the hearts of paleoclimatologists. That’s because both locations have ice that hasn’t melted for hundreds of thousands of years, providing an uninterrupted climate record. Ice cores drilled from ice sheets in Greenland have helped researchers reconstruct the history of its climate dating back about 130,000 years. But the ice record there doesn’t go any further.

When Moseley heard about the cave in Greenland, she knew that one way to push beyond the 130,000-year-old record was to look for speleothems, which can stretch back several hundred thousand years. But it wasn’t until five years later, after she’d begun a research position at Innsbruck University, that she began seriously thinking about making the trip.

The Wulff Land Cave still seemed out of reach, but among the papers that Self had given Moseley was a 1960 article authored by William Davies and Daniel Krinsley, the same geologists who’d photographed northern Greenland from the air. The men had been able to explore other caves on the more accessible northeastern side of Greenland. What most excited Moseley was the authors’ mention of “a flowstone deposit four inches thick formed of coarsely crystalline calcite” on the floor of one of the caves, topped by “stubs of stalagmites.” This was proof that the caves contained speleothems that could be brought back and studied in the lab. And since no one had ever constructed a cave-based climate record of Greenland, it would be an important contribution to science. But first she had to get there.

Researching polar outfitters, she found an explorer named Clive Johnson. She explained she wanted the cheapest trip she could get. “He stripped out helicopters, which was a big cost,” Moseley says, but that meant the group would have to make a punishing trek across rugged terrain carrying all their gear. The new figure seemed unattainable. Determined, Moseley applied for small grants and reached out to potential donors. In the end, a total of 59 individual and institutional sponsors—including the National Geographic Society—provided the funds she needed, about $125,000.

On July 29, 2015, Moseley and Shone, along with three others, boarded a plane from a Danish military base and flew to an airstrip next to Centrum Lake in northeast Greenland. Along with their camping gear and rations, the group had brought along an inflatable boat and an outboard engine. The plane flew off, leaving them to chart their course through the brown Arctic wilderness.

(Inside the race to rescue Arctic relics before it’s too late.)

After crossing the lake, the expeditioners set up base camp and then began a three-day trek to the valley where the caves were located. Most team members had put in months of physical training to prepare for this arduous hike. Each had taken courses on how to defend themselves in case they ran into polar bears, including the best ways to set up camp and how to use flares and rifles (a last resort).

What they weren’t ready for was the mosquitoes—relentless clouds of them. “At one point I counted more than 200 bites on one arm,” Moseley says. They also weren’t prepared for the scale of the landscape. “There’s nothing to give a sense of proportion,” Shone says. “You see a river and think it’s just a short walk, but it’ll take half a day to reach it.”

They ended up documenting 26 caves, including several that had not been explored previously, and collected 16 speleothem samples. They trekked back to camp over two days with their bags nearly bursting with pieces of flowstones. “I got this little video of Gina with my phone,” Shone says. “She can barely walk because she’s got this massive rucksack full of samples.”

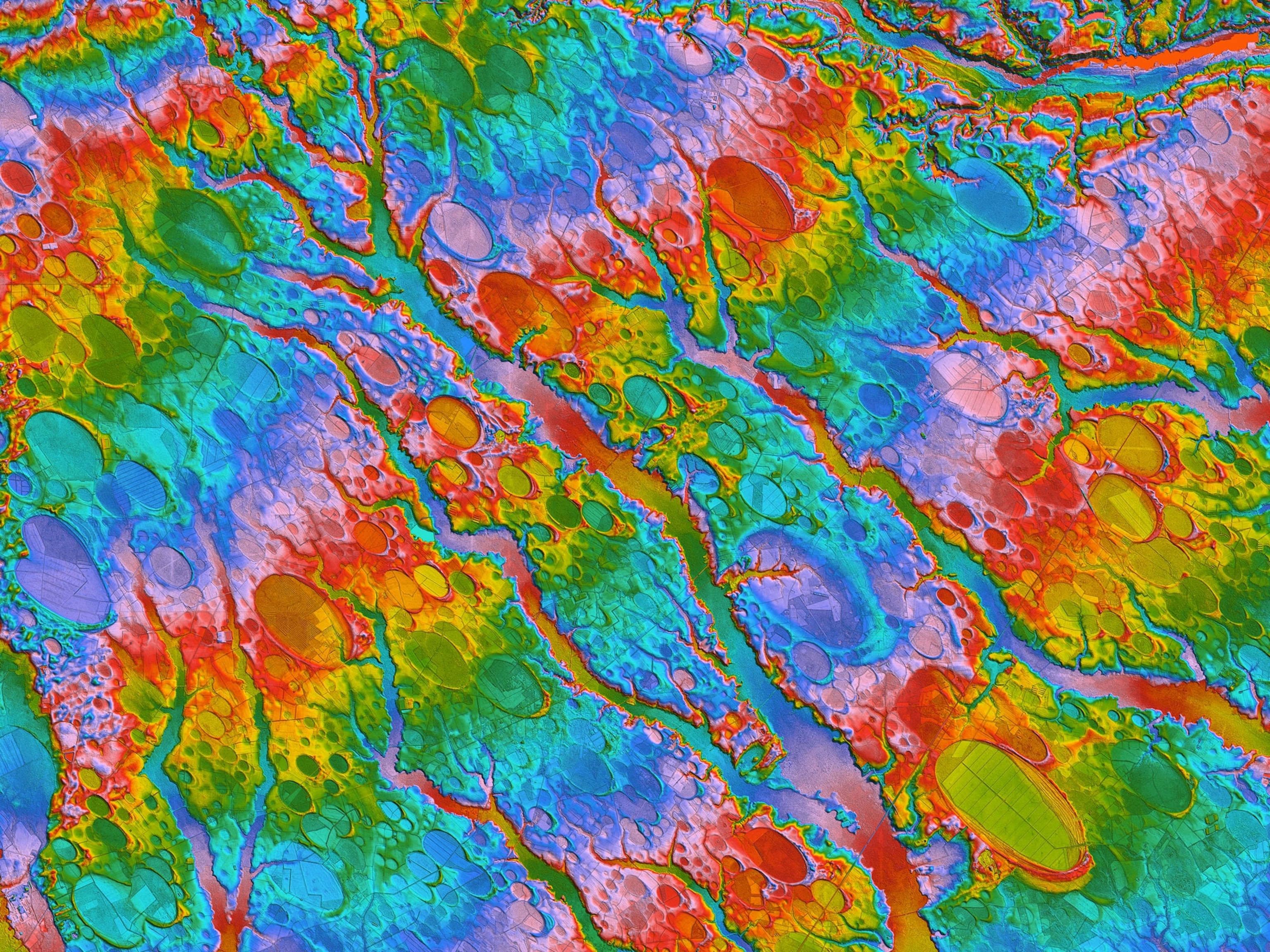

Their hard work paid off. A radiochemistry analysis of one sample showed that it was formed between 537,000 and 588,000 years ago. Since the creation of speleothems requires the drip or flow of water, the very existence of the sample analyzed by the researchers indicates that Greenland was wetter and warmer back then.

Moseley led two more Greenland expeditions to other caves in 2018 and 2019. With each punishing trip and a growing collection of speleothems, she was traveling back in time and creating a detailed archival record of Greenland’s paleoclimate.

Still, the Wulff Land Cave loomed. “I couldn’t get it out of my head,” Moseley says. But accessing it would require more funds and more planning. She’d need a helicopter, and there would need to be an advance trip to cache aviation fuel.

Finally, in July 2023—after the birth of the couple’s daughter, waiting out pandemic lockdowns, and raising about $400,000 from more than a dozen supporters, including an award from Rolex’s Perpetual Planet Initiative—Moseley, Shone, and three members of their expedition team took off from Iceland and flew to Wulff Land, about 30 miles from the large cave and a cluster of others they’d identified. The team planned for the helicopter to fly them back and forth from base camp to the rock formations, allowing them to explore the whole area. For that to happen, the weather had to hold.

On the first day of exploration, the visibility was good. “It felt like a dream,” Moseley says. As the helicopter approached the cliff, they could see the mouth of the cave. Again, without any familiar objects for scale reference, the opening didn’t seem that big. Blakeley, the technical climbing specialist, remarked, “Well, that’s an anticlimax.”

Blakeley and Shone headed out to scout the site. Once atop the cliff, Blakeley built an anchor point and began rappelling to the cave entrance. He had been gone for some time when Shone heard him shout for more rope. He had 150 meters, Shone thought. Shone came down after him, wondering how Blakeley could possibly have run out of rope. He looked down and saw Blakeley. “I saw how small he looked in comparison to the cave entrance,” Shone recalls. “And I thought, Oh my goodness, this is a giant cave.”

(The surface of the moon is hostile. A newly found cave could be a lifesaver.)

The pair returned with the exciting news. With great anticipation, four members of the team ventured out and down the cliff to the entrance. Together, they finally stepped inside.

It felt as if they had walked into a cathedral—the cave ceiling was at least 130 feet high. Birds nesting inside the cave soared high above their heads. “There was a turquoise, icy pool near the entrance,” Moseley says. “The floor was strewn with huge boulders the size of cars.” At the back of the cave, they observed several passages high up and large hoarfrost crystals covering the walls.

Impressed as she was by the mammoth size, Moseley also had reason to be disappointed. There were no speleothems. Even if any had formed in the past, they were likely to have been crushed by the boulders that covered the floor.

There were, however, the other caves to explore in the vicinity, but bad weather slammed shut the window of opportunity. Low clouds and strong winds combined with fog and snow made it risky to fly the helicopter. The team had to wait, hoping for the weather to turn. “We spent a lot of time sitting around at base camp, drinking cups of tea and dreaming about what we could be doing,” Moseley says.

But the weather did lift, allowing two teams to explore the other nearby caves. Moseley and Shone discovered one that had several passages with walls covered in ice and ice crystals. Shone was preparing to photograph it when Blakeley—rigging ropes to another cave—called on the radio. He’d spotted speleothems. Moseley and Shone raced to collect what would prove to be the only cave samples they’d bring back from the trip. That’s the thing about expeditions to unknown places, Shone says: “You never really know how they’re going to turn out.”

But you also never really know where science will lead you. Several months after returning from Wulff Land, dating analysis came back for the handful of speleothem samples they were able to collect in 2015 and 2019. The dating methods Moseley’s lab normally uses can go back only about 600,000 years, but she’d found a lab in China that used a method that could go much further back in time.

According to their analysis, samples collected in 2015 and 2019 are several million years old—a stunning result. “The samples grew during a time when atmospheric carbon dioxide levels were either similar to today or where they’re projected to be going in the next few decades to centuries,” Moseley says, her voice rising with enthusiasm.

Study of the 2023 specimens continues, and Moseley is hopeful that they too will reveal deep insight into Greenland’s past. But the 2015 and 2019 results are thrilling—perhaps as thrilling as climbing down a cliff face to reach a cave no one has ever entered before. “It’s a world where the atmospheric composition resembles the present. We can learn a lot about the state of the Arctic climate under those conditions to better inform ourselves about the future,” she says. “That’s exciting but perhaps also terrifying.” But pushing herself—and pushing the science—into the unknown is just where Moseley wants to be, perched on the edge of discovery.

The nonprofit National Geographic Society, committed to illuminating and protecting the wonder of our world, funded Explorer Gina Moseley's work. Learn more about the Society’s support of Explorers.

Yudhijit Bhattacharjee’s first foray into geology journalism was at age 10, when he tagged along with his geologist dad to document sites in Rajasthan, India.

Robbie Shone, an accomplished cave photographer, Shone became an Explorer in 2018. For this story, he conquered brutal weather, rugged terrain, and dangerous climbs.