The U.S. built a covert Cold War base under a Greenland glacier. Its secrets are now being revealed.

It was a secret nuclear-powered city built deep within a glacier. Its true legacy is only now being revealed.

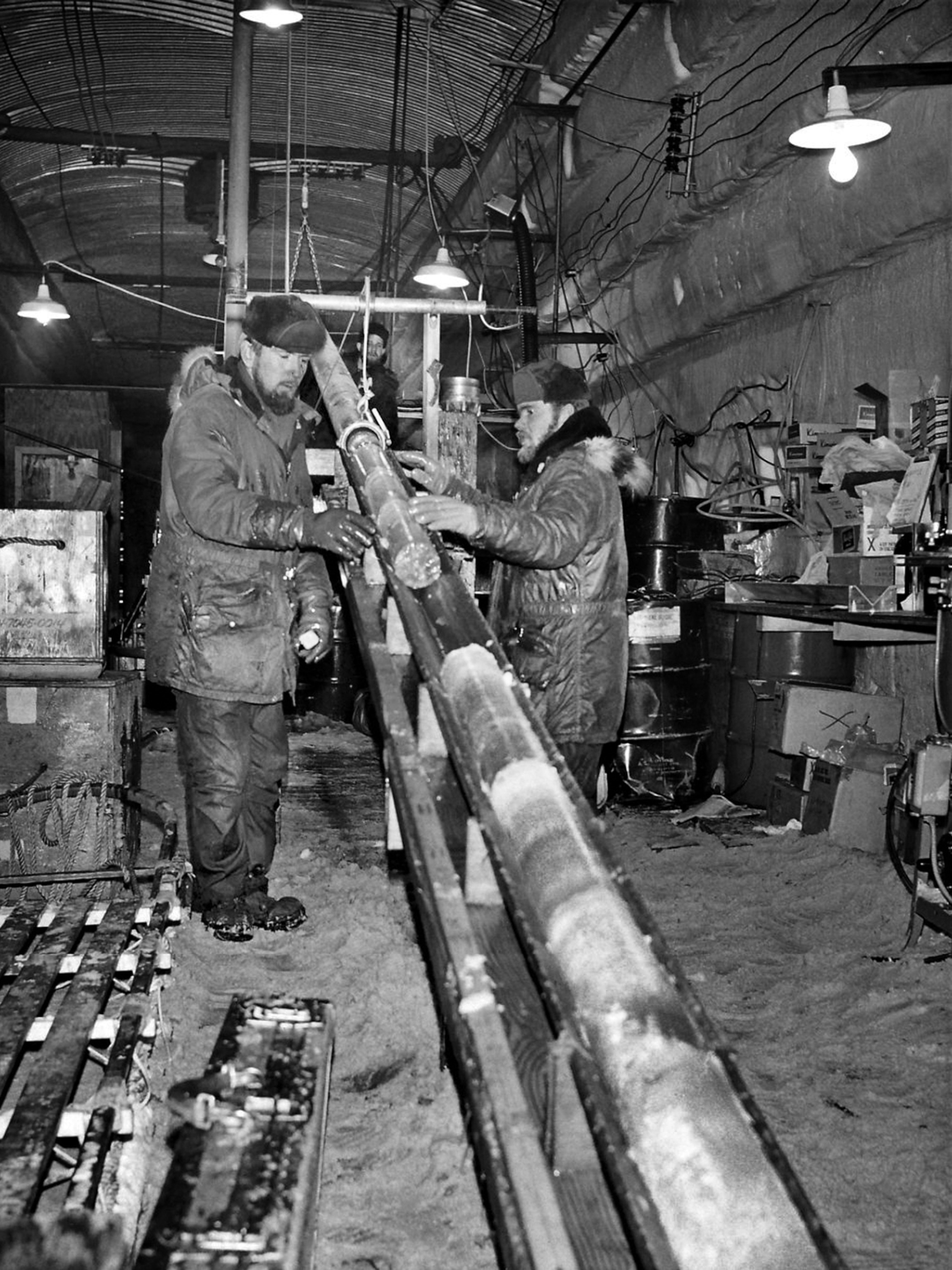

On a freezing day in October 1960 a team of U.S. Army technicians toiling at the top of the world stood in the belly of a glacier, making the final preparations that would bring a nuclear reactor to life.

It was an experimental model, smallish and fickle, and these, of course, were the early years of atomic energy; the men knew that a single burst of radiation could kill them. They were surrounded by walls of glistening snow that muffled their voices, reflected the beams cast by their lights, and absorbed the tick-tick-ticking of their Geiger counters. Far above their heads arched a ceiling of corrugated steel. Beneath their feet lay a mile-thick slab of ice so old it reached back to the Pleistocene. When the chain reaction finally began, there was a flash of relief, maybe a tight shout of triumph in the nearby control room. But within minutes the team was scrambling to shut the reactor down. Somewhere deep in the ice was a leak. Radioactive neutrons were spilling into the darkness.

(Step inside the nuclear-powered city the U.S. hid deep inside a glacier with our interactive map.)

Imagine the men there for a moment, encased in a glacier in Greenland, struggling to fire up a reactor—perhaps the only humans to be so perfectly suspended between the Ice Age and the Atomic Age. No one had ever done what they were doing. And no one would ever try it again. Publicly, the elaborate gambit they were a part of was meant to project American ingenuity: the careful construction of a vast under-ice military base, named Camp Century, that would show the world that the United States could transform even the coldest, harshest environment into a habitable place. It would be the ice fort to end all ice forts. The world’s first atomic-powered military station carved into a glacier was a triumph of engineering, a victory over the elements, its brave crews bringing civilization and scientific rigor to the polar waste.

After Camp Century was up and running, newspapers and magazines—including National Geographic—sent reporters to visit the Arctic outpost and tour its labyrinth of tunnels, all lit up by that reactor (by then its leak fixed with lead bricks and a lot of inventive engineering). What the visiting journalists weren’t told—nor were many of the soldiers living at the station, which could house up to 200—was that Camp Century was a cover for a secret Cold War Army project. Unknown even to Greenland’s Danish government, the plan remained classified for decades. America’s ambition in the frozen north wasn’t so much about developing portable atomic power as it was about turning the ice cap into a sprawling ballistic missile base. The Army, according to now declassified documents, cited the area’s “unique adaptability” to nuclear deployment—remote, near Russia, and hard to target. The plan, known as Project Iceworm, imagined threading the tunnels of Camp Century and beyond with railway tracks that could covertly house and transport up to 600 nuclear-tipped missiles that could be aimed over the pole at the Soviet Union.

Today nothing of that audacious military scheme remains. Camp Century was abandoned long ago by the Army, and its tunnels beneath the snow were crushed and swallowed by the restless ice. But a more surprising legacy endures, thanks to several long-overlooked jars stashed away in deep-freeze storage for decades. Some of the last remnants of an unheralded scientific project performed at Camp Century, the unexpected evidence inside those jars is now offering modern scientists a startling glimpse into the wetter, wilder, and more chaotic age that may await us.

(The U.S. has tried to buy Greenland before. Here’s how those past attempts went.)

For the seven years that the base was operational, personnel at Camp Century labored and lived in extreme isolation. The base lay 127 miles away from the nearest human outpost—an Air Force base called Thule. Shipments of food, fuel, and equipment were dragged on sleds to Century in long convoys known as swings. This was how people reached the camp too.

Austin Kovacs, an Army research engineer now in his 80s who spent several seasons living at the camp, remembers that traveling by swing took many hours, even in the best conditions. And in bad weather—blizzards, whiteouts, the severe cold that could fall like a hammer—the journey might take days. Sometimes swings even got lost in the endless Arctic void. Still, the real risk, Kovacs says, was boredom at the camp. “People thought it was dangerous. And it was not dangerous. It was comfortable. And at times it was very, very monotonous.”

(Inside the race to rescue Arctic relics before it’s too late.)

The men lived in prefabricated bunkhouses constructed inside the ice. Kovacs worked in what was called Trench 33, where he researched and studied foundations to support large buildings on polar ice caps. There was no sunlight, no birdsong, no breeze. Movies were shown in the base theater at least once a week. The library offered a modest collection of books. The men showered and shaved in a communal bathroom, ate in a bright mess hall. All kinds of waste—trash, sewage, industrial chemicals, even the radioactive water used to cool the reactor—was dumped back into the glacier where it remains frozen in place. For now.

They drank water drawn from a well in the glacier, and once, when Kovacs and his comrades needed excitement, they lowered themselves down the well’s steel cable, dropping down a claustrophobically narrow ice shaft into an enormous pitch-black cavern. Hanging there in utter darkness was a thrill.

Kovacs remembers waking in the morning to a woman’s voice, in song, piped through the camp’s loudspeaker. “It was a popular song at the time,” he recalls. “But after a while—after weeks and weeks—it got to be too much. You just wanted her to stop.” Enough time has passed that now Kovacs can’t recollect the song or the singer, just the way her voice drifted through the darkness. “I wish I could remember her name.”

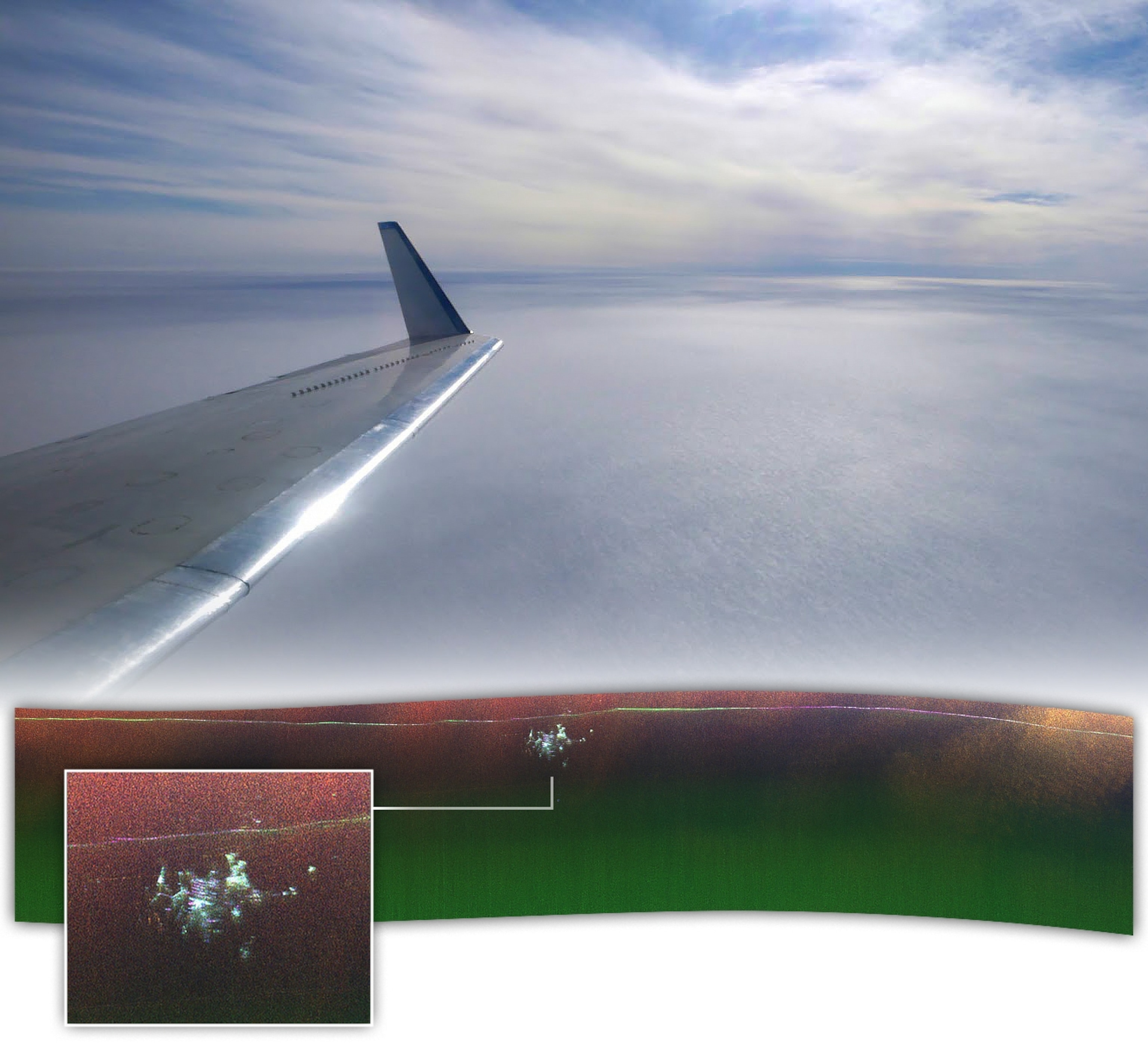

While Kovacs focused on his research, other men serviced the reactor or studied the movements of snow. At the bottom of the base, one team was busy drilling a hole deep into the ice. In 1966, after several years of steady labor, the men punched through the bottom of the glacier to the very surface of Greenland itself. They’d drilled more than 4,000 feet, gathering in the process the first ice core to ever penetrate an ice sheet. And almost on a whim they went farther too, collecting 11 and a half feet of ancient, frozen soil. They only stopped when a drill bearing burned out.

(Step inside Cold War nuclear sites with these stunning photos.)

That soil would form one of Camp Century’s most haunting legacies—though at the time no one thought much of it. For years after the base was abandoned, the soil was stored in jars in a freezer in Buffalo, New York, before being moved to a freezer in Denmark. There was little to suggest that something enlightening might be inside those jars—and few if any tools could help unlock their significance. It was only in 2019 that Paul Bierman, a geoscientist and professor at the University of Vermont, and several of his colleagues began to study the contents of the jars.

What they found has revolutionized our understanding of Greenland’s ancient climate—and offered a glimpse of our own possible future. Trapped in the soil, Bierman’s team discovered, were bits of leaves, twigs, mosses, even insects. The remains could only have come from a time when the region was free of ice, not smothered in a mile-thick glacier. The discovery painted a new picture of Greenland’s past. “There are things we can learn about ice sheets that we can never learn from the ice itself,” says Bierman. “It comes from the stuff below the ice.”

(Greenland could lose more ice this century than it has in 12,000 years.)

The soil samples provoked a radical departure from earlier, vaguer thinking that Greenland’s ice cap was a couple of million years old. Working with dozens of other scholars, Bierman showed that the ice cap was younger than anyone had imagined—the soil providing evidence that the land under Camp Century was ice-free about 400,000 years ago, during a period in which the landmass had been slightly warmer than it is today and when sea levels were significantly higher. What emerges from the data, he explains, isn’t merely an image of the past but also, perhaps, a clearer vision of a future in which quadrillions of gallons of fresh water currently locked up in the Greenland ice cap melt into the ocean. If that happens, the impacts will be felt nearly everywhere, as coastal cities and farms are inundated, potentially turning billions of humans into climate refugees.

“It’s easy to compartmentalize Greenland—to say, ‘Oh, that’s the Arctic. It doesn’t matter to me,’ ” says Bierman. But the long-forgotten soil from Camp Century draws a straight line to the critical issue of our age. “It takes you from 1966 to global climate change and onward to the effects of Greenland’s melting. That’s pretty profound.”

Project Iceworm was doomed from the start. What those Cold Warriors seemed to have miscalculated when they were sketching out their missile tunnels beneath the snow was how much they could prevent glaciers from behaving as if they’re alive. They slide and shrink, grow and flow. Building inside the glacier was too unstable and required too much maintenance. Rigid steel railways could buckle under the movement of the ice. Missiles might tip over. The atomic reactor—connected to a web of pipes, vents, and conduits that were themselves in motion—was at risk as the ice below it shifted. Soldiers armed with electric chain saws roamed the narrow tunnels, working like sculptors, carving back the relentless snow. Army planners eventually had to admit that none of this was a good idea. In 1963 the camp’s reactor was shut down, and three years later Century itself was abandoned.

When Kovacs returned in 1969 to conduct a survey, he found a total ruin. In a series of photographs he made of the base, one can see something like a mining disaster unfolding in slow motion. Tongues of snow spill down passageways. Steel structures collapse on themselves. Wood beams splinter like bones. The photos give form to the glacier’s overwhelming and otherwise invisible weight. Humans had been gone only a short time, but already there was the suggestion of an inevitable one-way journey—the debris being crushed, then swallowed, never to rise again.

All but forgotten for half a century, the camp today delivers a clear-eyed picture of Cold War excess, as well as a dose of nostalgia for a time of grandiose projects. “Think of all the energy and resources it took to do this,” Bierman says, “to build those tunnels and put soldiers down there. It’s almost science fiction. No one would dream of doing that today.”

(A thawing Arctic is heating up a new Cold War.)

For all that planning, none of the base’s big-thinking architects would ever have imagined that Camp Century’s enduring legacy would be the research conducted there—all part of the guise to hide the camp’s ulterior nuclear aims. Scientists like Bierman are grateful for that irony. “Especially when you realize those guys, drilling down in that trench back in 1966, had no idea what would happen. No idea how important it would be. And they just kept going.”

A writer for National Geographic since 2008, Neil Shea lives in Brooklyn, New York, and specializes in stories on the Arctic.