Severance is filmed in a real office building—one that reimagined corporate life

Endless hallways. Distant departments. The hit show is filmed at Bell Labs, an office complex in New Jersey that’s just as massive and eerie—and has an iconic history in its own right.

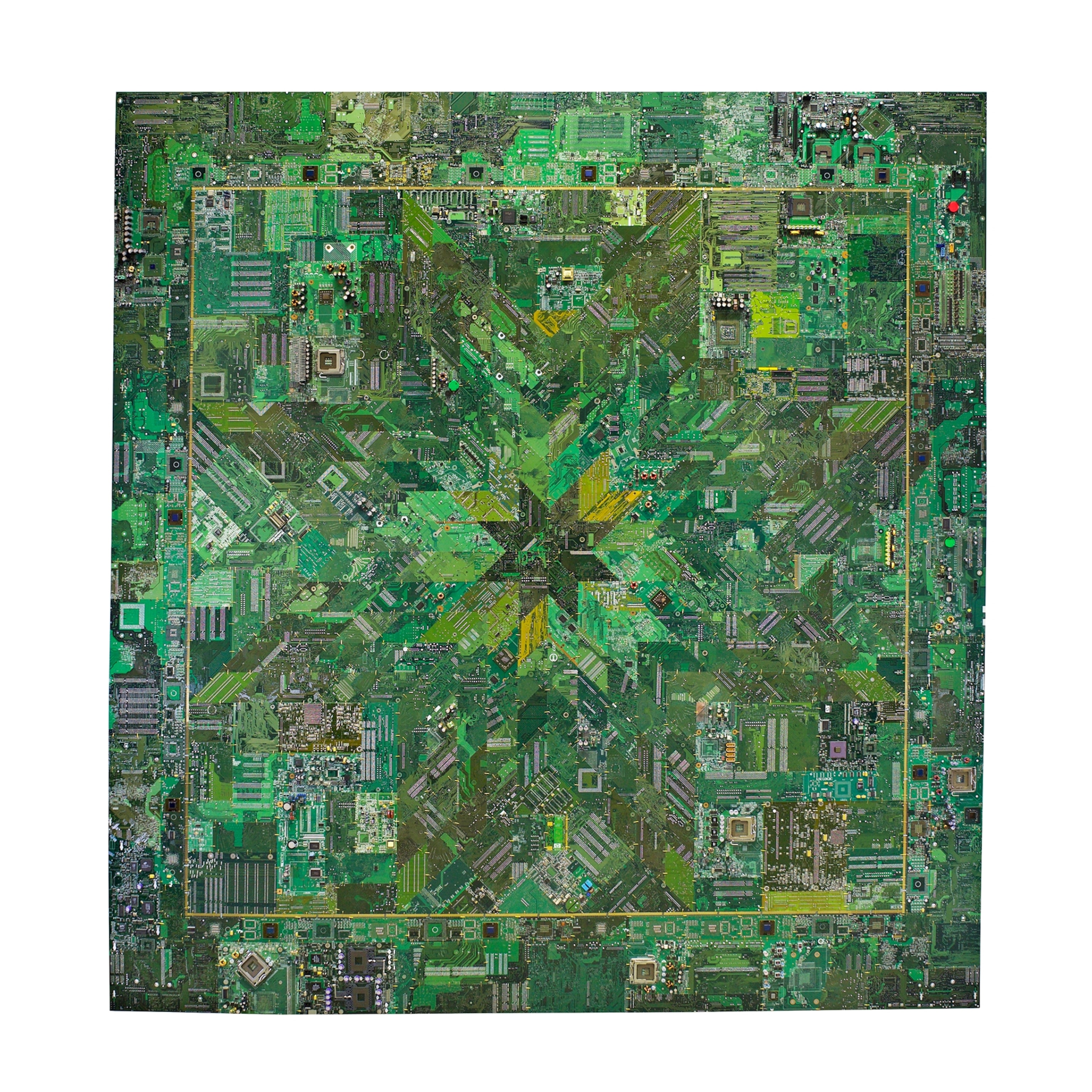

In the hit Apple TV series Severance, the microchip-bearing employees of Lumon Industries traverse the eerie halls of a massive office building that serves as a kind of corporate hell. The hallways are sterile and seemingly infinite—and the departments spread so far apart that employees need maps to find each other.

But that imposing building isn’t a Hollywood soundstage: It’s filmed at the real-life Bell Laboratories complex in Holmdel, New Jersey, one of the last works by famed architect Eero Saarinen.

Reimagining the workplace

Bell Labs is iconic as both an homage to the mid-century modernist aesthetic and as home to innovations that helped reshape the American workplace.

Bell Laboratories was a research group that grew out of the telephone companies founded by the telephone’s inventor, Alexander Graham Bell. Over the years, this group became known for its groundbreaking work in telephone and radio communications: Bell Labs workers invented the transistor, made some of the earliest lasers, and even discovered cosmic radiation confirming the Big Bang theory.

(What is Cold Harbor on Severance? It could be tied to this Civil War battle.)

But to do all that they first had to attract and retain the best talent. As historians Scott G. Knowles and Stuart W. Leslie note, at the end of World War II, major corporations shifted to building research “campuses” like Bell Labs as a way to “lure the best scientists and engineers away from academic and government positions” with roomy, modern complexes.

As corporations consolidated, they looked for landmark architecture that expressed their modernity and clout. Corporate campuses were the perfect way to both project a company’s power and attract top-notch talent. Saarinen would be a key part of this movement, designing corporate campuses for a variety of the era’s most powerful companies.

When Saarinen received his commission to design a new campus for Bell Laboratories in 1958, the Finnish American architect had already made a name for himself with iconic designs like St. Louis’s Gateway Arch, the massive stainless-steel monument on the Mississippi River. He was joined by Japanese American landscape architect Hideo Sasaki, renowned for his designs for Harvard and other modernist architects. Together, they designed what Bell Labs advertised as “a building created for people…giving us privacy and a controlled environment in which to work.”

The Bell Laboratories building

Saarinen’s vision for Bell Laboratories was unique in American architecture at the time. The 460-acre complex’s flagship building, a 700-foot-long cube, featured a first-of-its-kind mirrored “curtain wall” that covered the entire exterior of the massive building in thousands of individual glass panes. The mirrors reflected the landscape outside while providing natural light for the building’s interiors. Inside, the ultra-modern building contained an iconic atrium with blocky balconies.

Open hallways with hidden side corridors and moveable partitions allowed workers to collaborate without creating “unnecessary traffic,” according to a 1961 feature by Asbury Park Press writer Adrian F. Heffern.

(What working long hours does to your body.)

Outside, the building was surrounded by elliptical features, including two lakes and curved parking lots, and Sasaki’s landscape was also home to a three-legged, modernist water tower reminiscent of a transistor—one of Bell Laboratories’ signature discoveries.

Saarinen died before his creation was finished, and his work was completed by his architectural firm. When it opened in 1962, it was heralded by critics and locals alike.

“Bell Laboratories is a leading example of a teeming activity that has settled into a residential area in good harmony,” wrote architect Bernard Kellenyi in The Daily Register in 1966, touting its “parklike environment” that blended into its locale.

Building corporate alienation

But Bell employees didn’t necessarily agree. According to Knowles and Leslie, the new building’s interior hallways actually served to separate departments—making it more challenging for researchers to collaborate rather than easier as had been intended.

“The offices and laboratories themselves seemed strangely sterile,” they write, citing employee complaints about the difficulty of navigating the massive campus and their abandonment of some its key features in favor of finding the shortest, if less aesthetically pleasing, routes to their destinations.

(How new technology transformed the American workforce.)

Though the complex won a number of awards and was home to a number of important research advances—Bell Laboratories scientists conducted Nobel-winning laser research there, in addition to birthing radio astronomy—its heyday would not last. Corporate mergers and changing technology doomed the complex within just a few decades.

In 1984, AT&T bought Bell Laboratories, and the building was subsequently sold to Lucent Technologies and Alcatel-Lucent. (Today, Bell Laboratories is owned by Finnish cellular giant Nokia.) In 2006, Lucent sold the building to a real estate investment firm, which planned to raze it. The deal eventually failed, but not before an uproar among locals, former employees, and preservation groups, which began to advocate for its preservation.

Meanwhile, the building was abandoned, its mirrored windows surrounding empty atriums and corridors—a hollow symbol of the exact kind of corporate alienation embodied by Severance.

New life for old concepts

But Bell Labs’ life wasn’t over yet.

Today, after being purchased by Inspired by Somerset Development, it’s home to a new experiment in mixed-use zoning. Bell Works, its newest incarnation, is an experiment in what its creators call the “metroburb,” a term coined to describe a kind of public commons that today includes a public library, shops, tech companies, office space, dining and local events.

The once-abandoned complex has come back to life and is protected by historic preservation laws. But its legacy as a site of corporate dominance and uncanny career life remains thanks to shows like Severance that make the most of its looming, seemingly hostile architecture.