Who was the real Macrinus, Rome’s North African emperor?

In "Gladiator II," Denzel Washington plays Macrinus, the namesake of a historical emperor with a thrilling story.

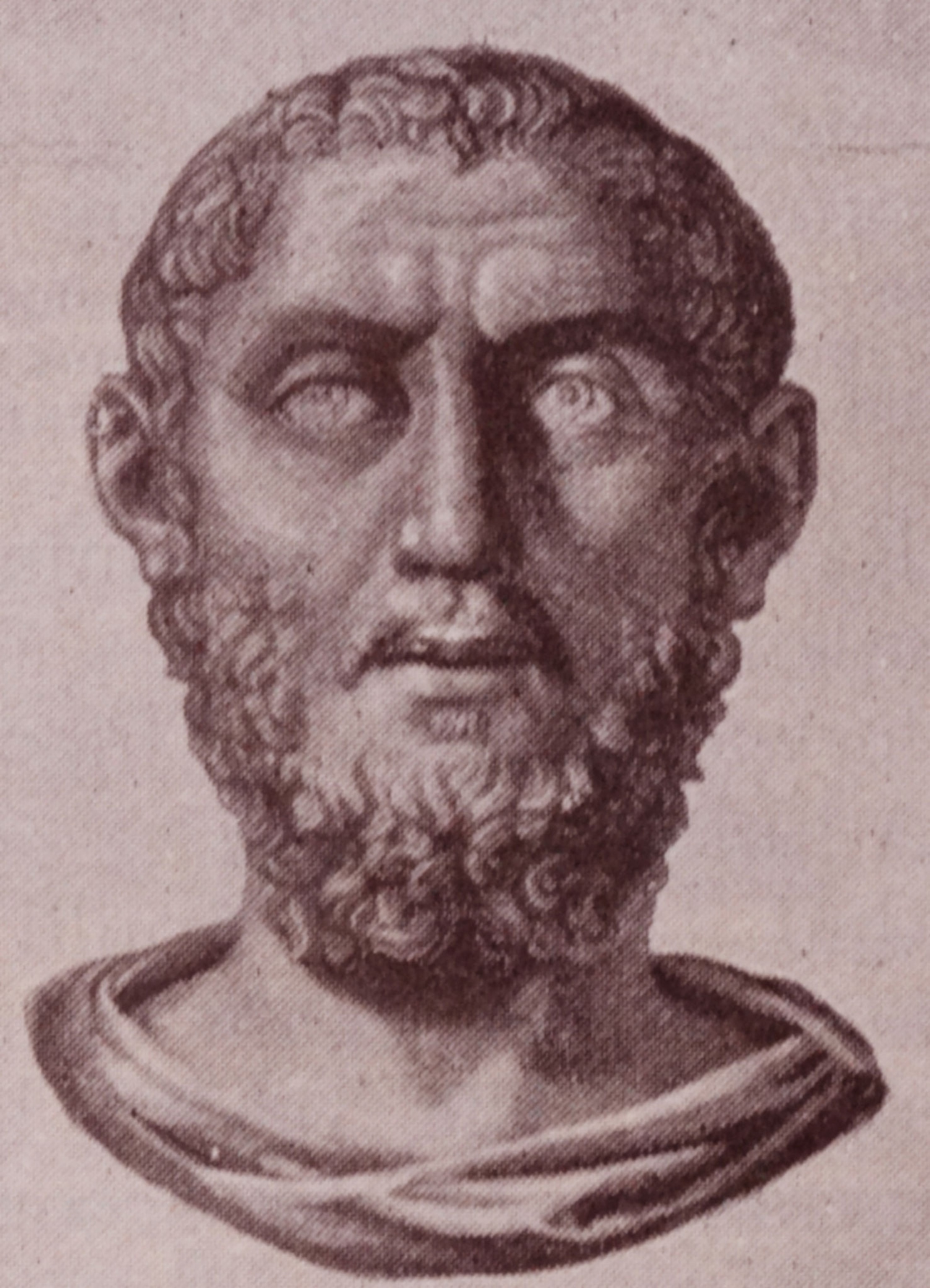

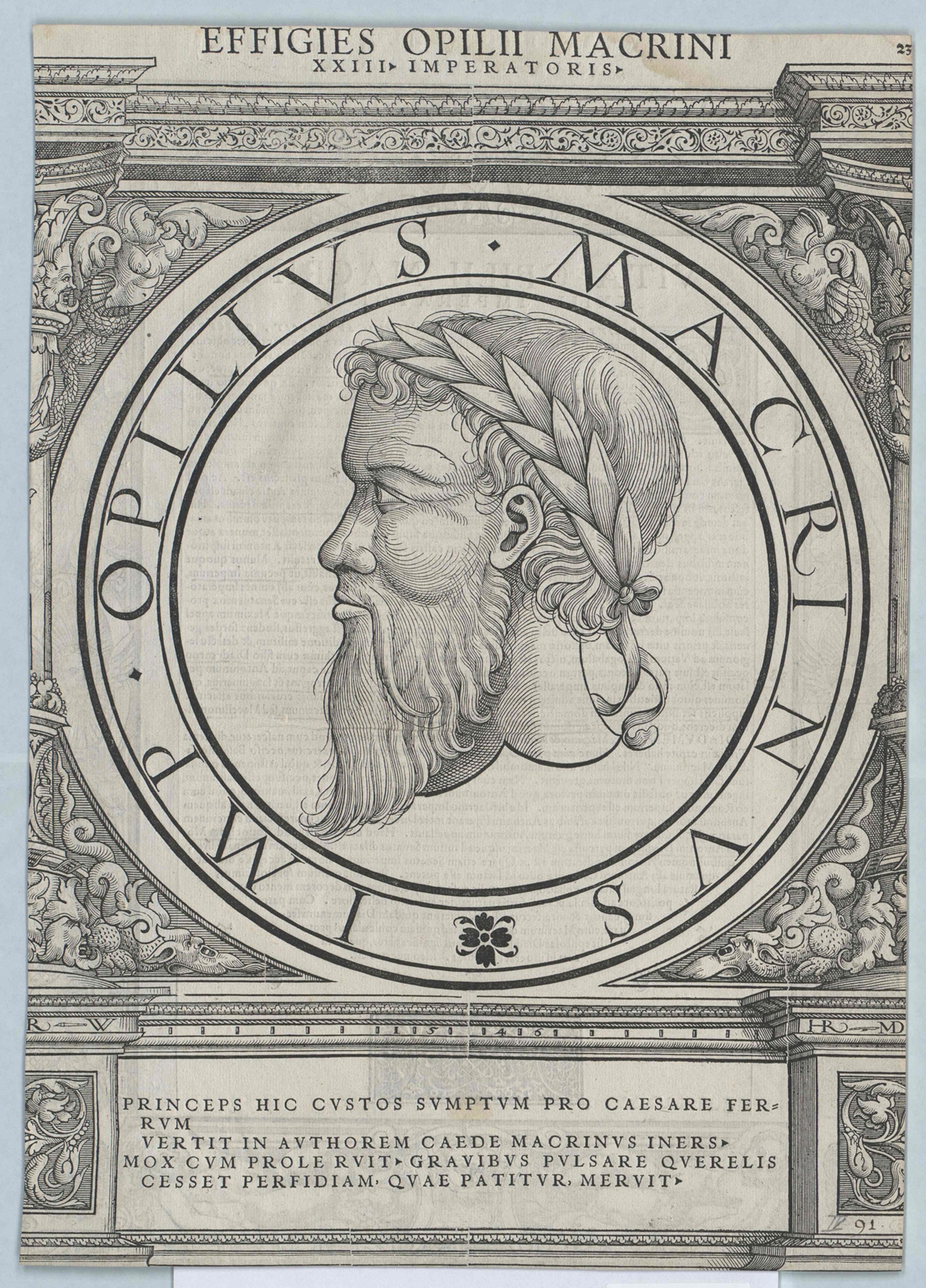

Born in what is now Algeria, Marcus Opellius Macrinus was one of only a handful of Roman emperors who had come from Africa.

Now, Macrinus shares a name with a character in Gladiator II. Played by Denzel Washington, the character carves his own path to power in the treacherous courts and arenas of third-century Rome.

The historical emperor also lived in the third century, but had a different backstory. He catapulted from obscurity to become the most powerful man in the empire. His meteoric rise showcases the diversity of the ancient Roman world––and how ethnicity or place of birth weren’t barriers to power.

Macrinus’s story starts in Roman North Africa

In A.D. 165, Macrinus was born in Caesarea, a seaside city in the Roman province of Mauretania. A wealthy provincial capital, Caesarea was similar to other prosperous cities in Roman Africa, such as Alexandria and Leptis Magna.

Thanks to Rome’s conquest of places like Carthage and Egypt, the region of North Africa was firmly established in the empire. Roman Africans sometimes traveled to the far reaches of the empire. For example, when scholars studied the remains of an elite Roman woman who had been buried in York, England, they found that she or one of her ancestors may have come fromNorth Africa. This discovery shows how interconnected, diverse, and cosmopolitan so much of the Roman world was.

Indeed, Roman Africans occupied virtually every social class, from enslaved laborers to soldiers stationed in Roman Britannia, scholars, and businessmen. And in 193, Libyan-born Septimius Severus became the first Roman emperor from Africa.

Modern racism wasn’t part of ancient Roman life, but Romans still articulated differences, promoted stereotypes, and harbored prejudice. They believed different cultural and ethnic groups were distinct from each other and had their own innate characteristics.

Macrinus didn’t hide his Africanness. According to ancient historian Cassius Dio, he even had a pierced ear, which Dio identified as a custom among the people of his region.

Macrinus’s family seems to have been part of the equestrian class, which was similar to a knight. His family was what Dio called “obscure,” underlining their undistinguished status within the imperial pecking order.

It was the senatorial families like the Julii and the Claudii who had the keys to the empire, not families like Macrinus’s. Every single emperor that Rome had ever known had been part of this class, either through birth or attainment––until Macrinus.

From the provinces to the Praetorian Guard

Many details about Macrinus’s early life have been lost, but we know he received legal training before serving in administrative roles in lower-ranking positions of the Praetorian Guard.

Under Emperor Caracalla in A.D. 212, Macrinus was promoted to commander of the Praetorian Guard, a position that made him one of the most powerful men in Rome. A cross between secret service agents and imperial bodyguards, the Praetorians could quite literally make or break an emperor.

Though their political meddling was ongoing, the force changed the fate of the empire. In A.D. 41, the Praetorian Guard plotted and carried out the assassination of Caligula. A century later, they auctioned off their support to emperor hopefuls, helping Didus Julianus briefly rule the empire in 193.

The emperor Caracalla targets Macrinus

By 217, Macrinus joined Emperor Caracalla’s campaign against the Parthian Empire in Central Asia.

Caracalla didn’t fully trust Macrinus after allegedly hearing a prophecy that Macrinus would succeed him as emperor. Unpopular and brutal, he knew how to remove rivals, having killed his own brother Geta in 211. Now, he turned his attention to Macrinus.

Macrinus knew he had to strike first, and he likely arranged Caracalla’s assassination. While traveling to a temple in contemporary Turkey, the emperor was stabbed to death by a guard when the party stopped by the side of the road for a bathroom break.. The guard was swiftly killed, so no one was able to question him or determine if he acted under someone else’s orders.

According to third-century historian Herodian of Antioch, Macrinus didn’t want to look like a usurper. Instead, he respectfully cremated the fallen emperor and sent his ashes to his mother.

Macrinus the emperor

With Caracalla out of the way, Macrinus didn’t wait for anyone to crown him emperor. Instead, he seized the title for himself. Few seemed to mind, since they were relieved that Caracalla, ruthless and short-tempered, was gone.

Macrinus tried to position himself as a merciful ruler. At the time, one form of military discipline was decimation, a practice of killing one soldier out of every ten. According to Herodian, Macrinus instead promoted centimation, or the killing of one in a hundred.

Herodian believed that Macrinus’s self-positioning was performative. He accused Macrinus of trying to imitate Marcus Aurelius, the stoic emperor who was widely loved and admired. Macrinus’s affectations of stoicism were shallow, Herodian claimed, since Macrinus “indulged in endless luxuries […] while neglecting the administration of the empire.”

Some even accused the former administrator of being incompetent. Dio commented that the emperor’s “comprehension of [his duties] was not so accurate as his performance of them was faithful.”

People in Rome also held the fact that he was an equestrian against him. At the same time, they objected to his absence from Rome, since he had not come back to the city after Caracalla’s murder.

Crucially, Macrinus gradually lost the military’s support. They were ashamed that he had agreed to peace with Parthia. Dislike of the emperor grew further when Macrinus reduced the pay rates for new recruits in a bid to save money.

Macrinus’s sins caught up with him

No one loathed Macrinus as much as Caracalla’s family, who desperately wanted to regain the power they had lost. To that end, Julia Maesa, the slain emperor’s aunt, began spreading rumors that her 14-year-old grandson, Elagabalus, was Caracalla’s illegitimate son––and, by right, he should be emperor.

Some soldiers liked the sound of that, and they liked Julia Maesa’s money too. They quickly rallied around the teenager and proclaimed him emperor in May 218.

With his support dwindling, Macrinus’s days were numbered. Julia Maesa and Elagabalus marched against him and defeated him at the Battle of Antioch in modern-day Turkey. He was quickly tracked down and killed, having ruled just over a year.

From a provincial family to the most powerful man in the empire, Macrinus’s story began in a different place from the vast majority of emperors. But in the end, he died just as violently as so many before and after him.