These enigmatic documents have kept their secrets for centuries

From the Voynich Manuscript to the tablets of Easter Island, the craftiest cryptologists haven't decoded these mysteries of history.

One would think an ancient object covered in text—or symbols—would be an archaeologist’s dream. What better way to learn about the past than from the direct words of the ancients? The groundbreaking discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799 and its decoding in 1822, for example, unlocked the intricate details of Egyptian hieroglyphic writing.

But sometimes, archaeologists come across ancient texts that, as exciting as they may be, refuse to give up their secrets. Here are some, including a symbol-stamped clay disk, the Easter Island tablets, and a 16th-century world map depicting landmasses allegedly unknown at the time it was charted, that still grip onto their ancient mysteries. What secrets are they holding?

Symbols of the Phaistos Disk

The Minoan kingdom flourished on the Greek island of Crete between 3000 B.C. and 1100 B.C. One of the earliest urban societies, they built elaborate palaces and used sophisticated plumbing, heating, and sewage systems. They also may have left behind a mysterious six-inch, fired-clay disk, which Italian archaeologist Luigi Pernier discovered in 1908 in the ruins of the ancient palace of Phaistos. Dating from perhaps 1700 B.C., this amazing find bears a spiral of 242 stamped symbols. Many have recognizable shapes, such as a tattooed head, an arrow, a plane tree, a cat, and a beehive. They may represent phonetic groups or syllables, but there are too few of them to be deciphered. No other artifact has ever been found with the same symbols. Attempts to unravel its mystery—Cretan? Foreign? Syllabic reading inward? Alphabetic reading outward?—are as varied as its interpreters. The fact that symbols are stamped may suggest a capacity for mass production, although no other discovery supports that.

A few experts believe the disk is a hoax or forgery, but most accept it as genuine. Like other remnants of the enigmatic early Minoan culture, it continues to hold its secrets.

The Voynich Manuscript's unbroken code

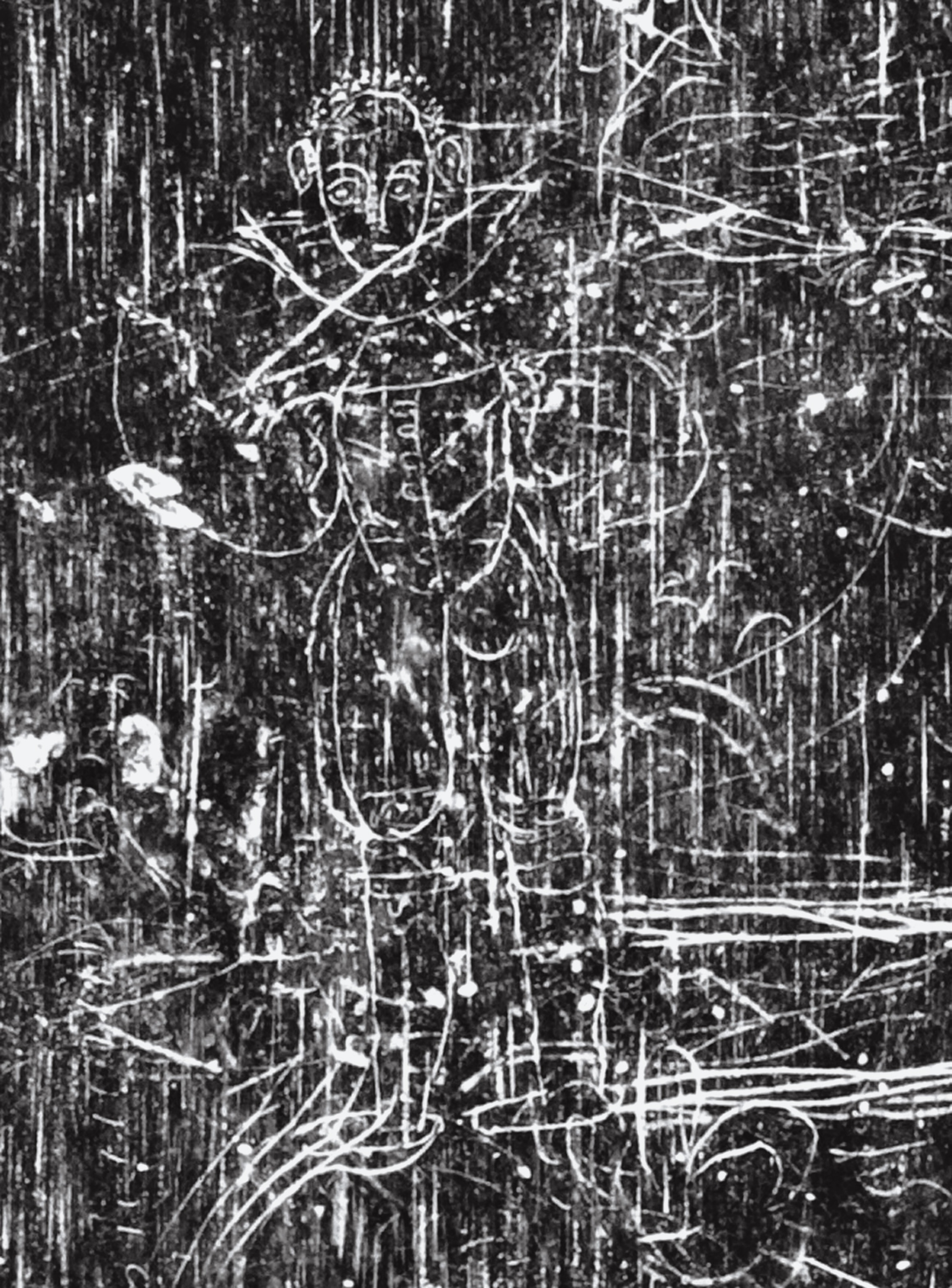

The Voynich Manuscript is both a code breaker’s delight and bane. The 240-page illustrated work is written in an unknown language and contains hundreds of inked illustrations of astrological symbols, unidentifiable plants, and bizarre human figures. It is divided into six sections (based on the illustrations): botany, astronomy and astrology, biology, cosmology, pharmaceutical, and a section of continual text with decorative markings. Legions of cryptographers have tried and failed to decipher the manuscript’s lettering. Is it an herbal manual? An alchemical guide? A researcher in 2019 claimed it is a female gynecology guide written by Dominican nuns.

(Did codebreakers crack this mysterious Medieval manuscript?)

Written on vellum (animal skin), the manuscript named after the Polish-American bookseller, Wilfrid Voynich, who bought it in 1912, but its provenance is much older. The work dates back at least to the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II of Germany (1576–1612), who acquired it for 600 gold ducats—though recent tests show it dates from the early 15th century. The manuscript then passed through various other European owners, none of whom could make sense of it. Claims of decipherment continue to this day without resolution.

Easter Island’s wooden tablets

Easter Island—Rapa Nui in the language of its people—in the South Pacific is well known for its mysterious, multi-ton monolithic statues, known as moai, but no one knows their purpose. The answer may lie in two dozen wooden tablets (and objects, including a chieftain’s staff) found at the site where they’re located. They contain an undeciphered rongorongo script, running left to right, then right to left when the tablet is upended. The glyphs themselves portray outlines of animals, plants, humans, and artifacts.

(Easter Islanders’ weapons were deliberately not lethal.)

It’s not clear when the writing system appeared. Some believe it developed long before the first Europeans arrived in the 1700s; though others argue it emerged after the Rapanui people first saw European writing. Whatever the case, the language was used until the 1860s, when most of the Rapanui died of European illnesses, and knowledge of the script went with them. Oral history suggests the writing was probably used for religious purposes, perhaps detailing stories about the creation of the universe and the natural world, and only the elite could understand it, but no one knows for sure.

Lands on the Piri Reis map

Hajji Ahmed Muhiddin Piri, better known now as Piri Reis (Captain Piri), was an accomplished Turkish admiral and mapmaker of the 16th century, known primarily as the creator of a beautiful 1513 map of the world. Lost for many years, a remnant of the map, drawn on gazelle skin parchment, was rediscovered in the 20th century and is now held in Istanbul’s Topkapi Palace.

Showing the western coasts of Europe, North Africa, and the Brazil coast, the map is remarkable for its depiction of South America’s coast in its proper longitudinal position in relation to Africa, only two decades after European discovery. But that’s not the biggest surprise.

Piri Reis notes on the map that he compiled it from many sources, including Portuguese explorers and Christopher Columbus’s recent travels, but that doesn’t explain everything. The map contains information about an interior mountain range in South America—knowledge that, in theory, was unknown at the time. Even more puzzling, the document is said to show Antarctica with great topographical detail—although its first sighting wasn’t until centuries later, in 1820—and without ice. Antarctica has been covered in ice for about 6,000 years.

For these reasons, some researchers surmise the map must have been created thousands of years earlier by an unknown, advanced civilization. The mystery remains: Who charted these details, and why has history forgotten these early explorers?

The Jamestown Slate

In 2009, excavations in an old well in Jamestown, Virginia, America’s first permanent European settlement, uncovered a colonial-era slate tablet covered with layers and layers of overlapping, scratched inscriptions. They include drawings of a man with a ruffed collar, what appears to be a palmetto tree, and words reading either “A minion of the finest sorte” (a minon, or minion, being either a servant or cannon), or the more modest “I am non of the finest sorte.” The slate’s marks and original owner, or owners, remain a mystery. The palmetto tree suggests the artist had been traveling south of Jamestown—he may even have been William Strachey, who survived a shipwreck in Bermuda to become the colony’s first secretary.

(Stolen from Africa, enslaved people first arrived in colonial Virginia in 1619.)

The well in which the tablet was found was dug around 1608 to 1610 in the center of James Fort under the orders of John Smith, Jamestown’s leader, and was made into a trash pit after it became brackish and unusable. Colonial trash is an archaeologist’s treasure, and the discarded slate is a particularly valuable find, even if its meaning is not readily available.

To learn more, check out 100 Greatest Mysteries Revealed. Available wherever books and magazines are sold.