The chaotic headlines, broken records, and remarkable strength that defined 2021

The year began with vaccines and optimism. But a new Covid-19 wave, violent conflicts, and the climate crisis made 2021 one more year we'd need resilience to survive.

In July 2021 the Indonesian photojournalist Muhammad Fadli drove with his cameras to a cemetery on the Jakarta outskirts and understood, again and more profoundly, how wrong he had been. Over a stretch of weeks during March and April, Fadli had let himself believe that life as he knew it was righting itself: He saw a nationwide inoculation campaign, markets starting to bustle again, malls reopening.

But no. It was like that lull in the horror movies, the brief fake serenity before the thing roars up again. Now in this new burial area, one of six commissioned when the pandemic filled the city’s main public cemetery, earthmoving machinery was clearing more ground even as mourners bent over fresh graves.

At the entrance gate, Fadli noted, hearses pulled up every few minutes to deliver the dead. Frequently they converged and had to wait in line for their turn. When drivers swung open their rear doors, Fadli realized that many of the hearses held more than one casket. “Some were carrying four,” he told me in early September, and as both of us paused to picture this, our phone conversation momentarily fell silent.

Documenting the year inevitably pulled our photographers into scenes of anguish, despair, and loss. But they also witnessed beauty, resolve, and hope.

I was at home in California, where five northern counties were aflame and a separate 220,000-acre fire still was advancing toward South Lake Tahoe. Fadli was in Indonesia, where over the summer the daily COVID-19 infection rate had surged past India’s. “My brother-in-law, my father-in-law: COVID,” he said. “My sister-in-law: hospitalized for almost 15 days.”

And … ?

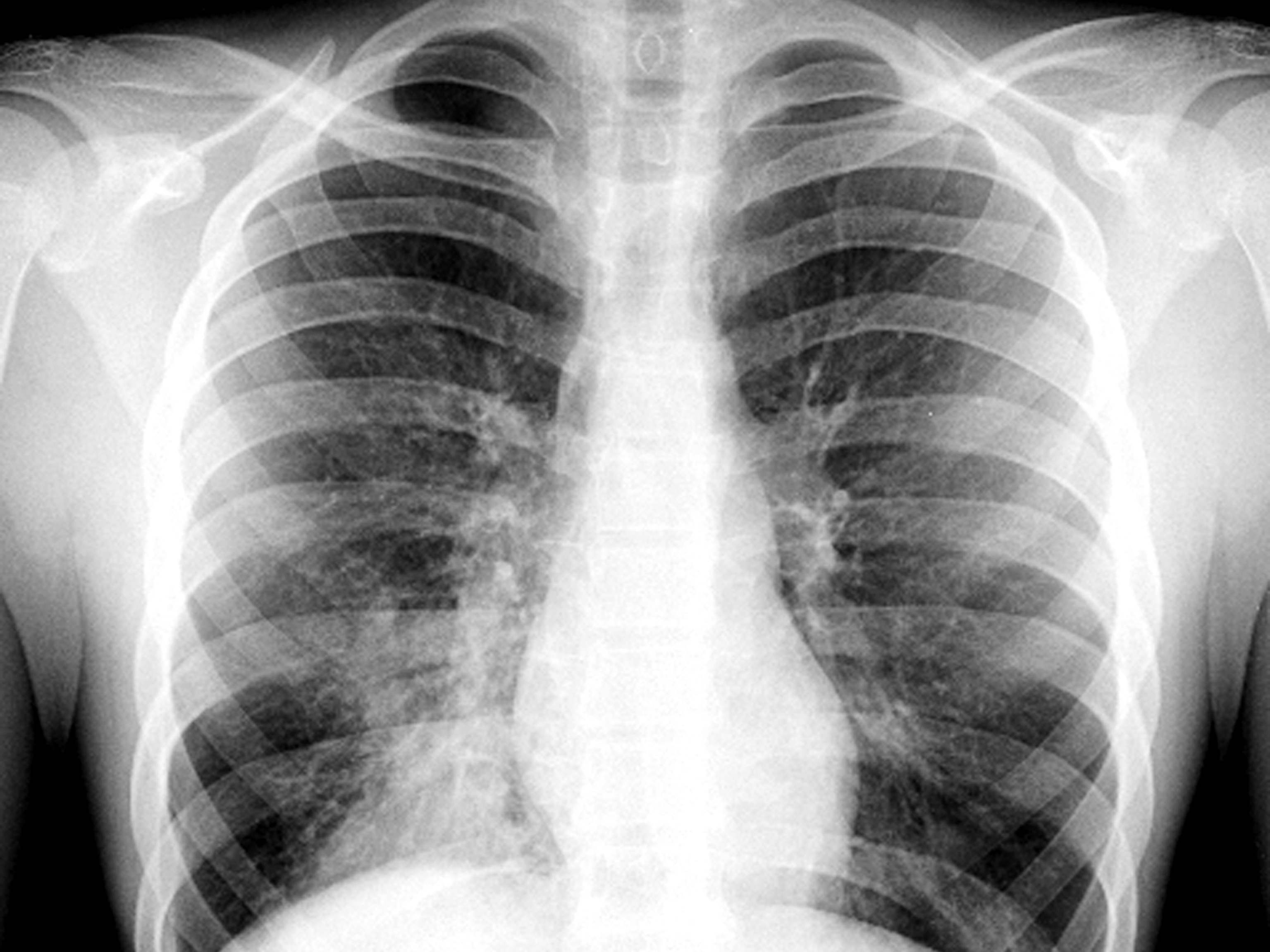

“Everyone survived.” Because they were lucky and—probably—because they managed to receive first vaccine doses before they fell ill. The Delta variant crushed India and Indonesia as it rampaged across continents this past year; a dispatch from Jakarta reported 114 Indonesian doctors killed by COVID-19 in one two-and-a-half-week period.

Documenting the year inevitably pulled Fadli into scenes of anguish, despair, and loss. But he also made pictures in places where he chose to see hope in the ferocity of human resolve. A city bus station repurposed as a mass vaccination site, crowded to the walls with Indonesians determined to get their shots. A classroom of face-masked children, respectfully dressed in necktie or hijab, their teacher amid the wooden desks with her arms full of schoolwork. Her masked smile shows in her eyes.

This is the second time that National Geographic has dedicated its January issue to photographers’ impressions from the just concluded year. In January 2021 the magazine published a visual distillation of the previous 12 months’ agitation and grief. Back then it was a relief simply to be done with that “harrowing year,” as Editor in Chief Susan Goldberg wrote in the issue, using language more dignified than “Dumpster fire,” which was a favored descriptor for 2020 where I live. The coming year seemed to hold so much possibility—the fastest new vaccine development in history, the most ambitious global inoculation plans in history, an international consensus that health-care workers and the elderly must be first on the priority lists for protection.

See all 46 photographs from our 2021 Year in Pictures issue here.

For many Americans, that anticipation of 2021’s emotional respite endured for ... you know ... a week. Six days, technically. In the section of this issue labeled Conflict, you’ll see Mel D. Cole’s shoving-melee photograph of January 6—as we now tend to refer to the violent breach of the U.S. Capitol by a mob protesting the 2020 election results that turned President Donald J. Trump out of office. As editors sifted through thousands of photographs from National Geographic’s 2021 storytelling, they found their themes (and alliteration): COVID fills another section, as do Climate and Conservation. There’s no abundance of respite in these pictures, to be sure. But there is beauty, and resolve, and hope. “Ordinary people,” Muhammad Fadli likes to say, “trying to help others.”

The lone man in mask and gown, standing above a wooded green valley, is Nazir Ahmed. He’s a health-care worker in the Indian territory of Jammu and Kashmir, looking for isolated shepherds to vaccinate against COVID-19.

The woman cradling a baby alpaca is Alina Surquislla Gomez. She works for a Peruvian breeders’ cooperative, advising traditional alpaqueros whose Andean water and grazing lands are menaced by mining pollution and climate change.

This was the year of Texas’ deep freeze in February, Canada’s highest temperatures in recorded history in June, and Germany and Belgium’s lethal flash flooding in July.

The Kenyan gently laying a gloved hand on a cheetah’s flank is a veterinarian named Michael Njoroge; he and the two wildlife specialists with him were part of a five-day effort, involving truck transport and IV hookups and surgeons, to keep a wounded wild animal alive. If you saw the August story on National Geographic’s digital platform, which was documented by Nairobi-based photographer Nichole Sobecki, you already know it is cause for turbulence of the heart. So much intention. So much kindness.

Sobecki had been working for months with Rachael Bale, the magazine’s animals editor, on their September article about an international animal-smuggling network preying upon Africa’s threatened cheetah population. Then a Kenyan guide, with Sobecki along, found an injured adult cheetah amid the brush of a national reserve. For 48 hours the two of them watched over the cheetah while waiting for the Kenya Wildlife Service veterinary team alerted by local rangers.

“One cheetah in one part of the world,” Sobecki said, and sighed. On a call between Nairobi and Oakland, California, she and I were trying to figure out how we felt about the push to revive the wounded female, which the rangers had decided to name Nichole. Uplifting and futile, both words apply; Nichole the cheetah did not survive. Her injuries appeared to have been caused by another animal, not a human hunter or smuggler. But Nichole the photographer has been documenting vanishing animal habitats and the climate crisis’s toll on Africa, and she was having a hard time disentangling one kind of sorrow from another. “There was a will to try to save that cheetah,” Sobecki said. “The efforts were ambitious and sweeping. I don’t want to minimize that.”

If events had transpired differently, though ... if the Wildlife Service vet had not been off duty the day they found the cheetah or the substitute team had arrived more quickly ... if human behavior hadn’t cost cheetahs more than 90 percent of their historic range … Yes, you could make the case that this particular cheetah was perhaps meant to have expired alone, under a bush, undisturbed by probing hands. But sometimes we fasten on small stories to help us hold bigger ones in our heads.

“Everybody grows up knowing about cheetahs,” Sobecki said. “What about the countless other species that are facing these same issues? If we can allow one of our most celebrated animals to reach a place where there are fewer than 7,000 adults left in the wild, what about everything else?”

Everything else. No easy delineation separates the images of this year. In 2021 the triumph of COVID-19 vaccine development set off its own discord. (Who knew we could summon such rage over injections to protect us from death?) Nearly every attempt at conservation—of species, of economies, of spots on Earth—took place against the existential backdrop of climate change. It was August 9 when the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a 2,000-page compilation of bleak assessments and predictions. Its sixth such report in the past two decades, this one was described by UN Secretary-General António Guterres as a “code red for humanity.” Less than a week after the report’s release, the 220,000-acre Caldor wildfire here in California ignited and spread through drought-parched foothills while firefighting crews farther north in the state were still exhausting themselves working another megafire, named Dixie.

The Dixie wildfire was the second largest in California history, not fully contained until the end of October. London-based photographer Lynsey Addario has devoted much of her career to capturing images of conflict—these pages include her devastating portrait, from Ethiopia, of a survivor of repeated rape by soldiers. Addario’s 2021 summer was spent in California, alongside men and women battling fire.

This was the year of Texas’ deep-freeze February, Canada’s highest-temperatures-in-recorded-history June, Germany and Belgium’s lethal-flash-flooding July. “Global weirding” is the term Texas Tech University climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe likes to use in the issue’s conversation with National Geographic’s Robert Kunzig and Alejandra Borunda and environmental author Katharine Wilkinson. Yes, that’s two Dr. Katharines, both exhorting us to refuse despair—and to allow ourselves the possibility, as Wilkinson says, that the present moment might be both a horrifying and a magnificent time to be alive on the planet. “We have so much power,” she insists. “There’s so much that we can do” to combat climate change. (You can read much more of their conversation here.)

“The pandemic isn’t going anywhere,” said a restaurateur whose business had cratered. “But we’re not going anywhere either. We’re stronger than that.”

As you examine these photos, maybe consider some of the 2021 headlines that did deliver on emotional respite, or at least one genuine moment of OK, breathe, managed to make it through that. The New Orleans levees held, remember? The Caldor fire turned away without reaching South Lake Tahoe. Until and despite the whack of the Delta variant, millions of us were able to return to the physical company of others—embracing, kissing grandparents, watching children go back to school.

The Howard University graduates, singing and dancing as they stroll together in robes and mortarboards, haul up my spirits every time I look at them. So do the shining South Texas teenage mariachis, buttoned and laced into their new charro suits, riding the bus to performances for the first time since the start of the pandemic. (How do you find moments of grace, beauty, and joy during a pandemic?)

The baby elephant sucking down bottled formula? Conservation meets COVID, with a surprise happy ending: In a Kenyan sanctuary that houses the elephants, pandemic shipping bottlenecks blocked the powdered milk supply. So the caretakers tried substituting locally available goat milk, and the new formula doubled the orphaned baby elephants’ survival rate—to almost 100 percent.

Even a whole “Year in Pictures” issue contains a finite number of pages, of course. An arbitrary partial list of notable people, places, and things from 2021 that are not found in these images: the Tokyo Olympics; private space launches; the sideways-wedged cargo ship blocking the Suez Canal; and the inauguration of the first Black, Asian American, and female U.S. vice president. The presidential assassination and catastrophic earthquake in Haiti. The Perseverance rover rock-boring into Mars. The July 4 week on Massachusetts’ Cape Cod, when tens of thousands packed the bars and restaurants of Provincetown, spilling out into the streets, because so many vacationers thought vaccination had finally made it safe.

The Provincetown revelry was referred to, in the dry phrasing of the ensuing Centers for Disease Control and Prevention alert, as “large public gatherings in a town in Barnstable County, Massachusetts.” For those of us who’d never had occasion to learn what breakthrough infections were, now we knew: Vaccinated people who traveled home from Provincetown were testing positive for COVID-19. Multistate tracing found only five hospitalizations among the 469 reported cases, and no deaths—so, yes, the vaccine protects. It doesn’t entirely prevent transmission, though, meaning no relaxing of our collective vigilance, not yet.

“The pandemic isn’t going anywhere,” Provincetown restaurant owner Rob Anderson said when I called in August to ask how he and others were managing. “But we’re not going anywhere either. We’re stronger than that. We’re still standing.”

Like others in town, Anderson watched his business crater in the weeks after the Provincetown breakthrough news, and he suggested I consider the way a tightrope walker reaches the end of each rope. “What do you do? You look ahead,” he said. “And you stay balanced. So that’s what we do.”

This has stayed with me: the tightrope walker. I was thinking about it—how hard 2021 has made us work sometimes, just trying to remain upright—when I called photographer Stephen Wilkes, who as we spoke was shooting the panoramic image that precedes this article. He was 45 feet in the air, photographing from an elevated lift that his crew had been allowed to wheel onto the National Mall in Washington, D.C. When making what Wilkes calls his Day to Night pictures, he works around the clock, taking multiple photos and later merging them into one sweeping image. For this particular Day to Night, he focused for 30 hours on the installation spread across 20 acres at the base of the Washington Monument: white flags, each representing a COVID-19 death in the United States.

“A sea of flags,” Wilkes said.

Then he corrected himself. Wait, Wilkes said. Not exactly a sea. “Because of the height I’m at, I can see them almost as individuals,” he said. “They remind me of flickering stars.”

The artist Suzanne Brennan Firstenberg designed the three-week installation as a giant grid, with open paths to let people walk among the flags, write names on them to remember the dead, and plant new flags as the death toll continued to grow. A large sign at the entrance carried the latest national cumulative numbers, which Firstenberg was updating by hand every day. “When I came yesterday, it was 666,624,” Wilkes said. “This afternoon it’s … ” He hesitated. I imagined him up there on his platform, holding his camera, squinting at the distant number to read it off right.

“670,032,” he said.

We did the math in our heads.

In the morning there’d been rain, Wilkes said. “I see an older gentleman, walking through the flags,” he said. “I see a woman sitting on the ground. Just planted a flag. She’s African American, has this light-green shirt on, she’s with—looks like her husband. They’re holding hands.”

The afternoon light was doing something remarkable to the monument’s shadowing, Wilkes said: luminous on one side, dark on another. “Beautiful,” he said. “And it’s starting to clear up. It’s spectacular, when the sun comes out. Because the white flags just glow.”

Cynthia Gorney is a National Geographic contributing writer. She wrote about toxic wildfire pollution in the April 2021 issue.

This story appears in the January 2022 issue of National Geographic magazine.