Sequoyah, the U.S. state that almost existed

It was planned as a Native American-governed state, until politicians folded Indigenous lands into Oklahoma—a decision that still impacts life there today.

Oklahoma’s name is derived from a Choctaw term for “red people,” yet its nickname—the Sooner State—comes from the white settlers who descended on it to claim Native lands.

That tension is nothing new. Home to displaced Native Americans who’d been kicked off their ancestral lands and white settlers eager to own it, the state is no stranger to tussles over who can really claim Oklahoma.

(North America's Native nations reassert their sovereignty: "We are here.")

For one brief moment in the early 20th century, it looked like there might be a solution: create one state for Native Americans governed by Indigenous leaders and another for white settlers. But though both whites and Native Americans living in the area favored the plan, the state they envisioned—Sequoyah—never came to be.

Here’s the tale of the proposed Indigenous-governed state of Sequoyah and its downfall—a story that still affects Oklahomans to this day.

A forced removal from ancestral lands

The conflict was actually born in the southeastern United States, where Native ancestral lands span from modern-day North Carolina to Mississippi. As white settlers flooded the area in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, they developed ties with the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole people, dubbing them the “Five Civilized Tribes.” Nonetheless, these white newcomers pressured the U.S. government to push Native Americans out of their lands.

In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which allowed then president Andrew Jackson to grant Native American tribes land out west in exchange for their ancestral lands. Under duress, the Five Tribes signed a variety of treaties ceding their lands in exchange for promises like an 1833 treaty that guaranteed “a permanent home to the whole Creek nation of Indians.”

(Will the U.S. uphold an 1835 treaty promising the Cherokee a seat in Congress?)

Though many went without resistance, others refused and were driven from their homes at gunpoint. Between 1830 and 1850, about 100,000 Native Americans were relocated—a forced migration known as the Trail of Tears.

The great shrinking of Indian Territory

Their new home was located a thousand miles away in Indian Territory, the area west of the Mississippi and east of the Rockies. There, the Five Tribes settled onto a corner of that land in what is now central and eastern Oklahoma alongside 21 other tribes.

Over the years, the United States claimed more Native land and Indian Territory shrank to roughly the boundaries of modern-day Oklahoma. In the 1880s, it shrank even further when the U.S. switched from a policy of removal to allotment, a system designed to force Native assimilation into white culture by dividing their traditional communal lands overseen by tribal governments into small, individually owned properties.

(A century of trauma at U.S. boarding schools for Native American children.)

The Five Tribes were excluded from the policy, so the eastern portion of modern-day Oklahoma remained Indian territory. But Indigenous tribes living in the western part of the region lost much of their land: The lands of tribes in western Oklahoma were carved into tiny portions and doled out to individuals, many of whom sold their shares to white settlers or the U.S. government.

Meanwhile, the two-million-acre swath of central Oklahoma that had been home to the Muscogee and Seminoles was suddenly up for grabs: The U.S. government forced the tribes to cede the land—now known as the Unassigned Lands—as retribution for siding with the Confederacy during the Civil War.

Boomers, sooners, and the birth of Oklahoma Territory

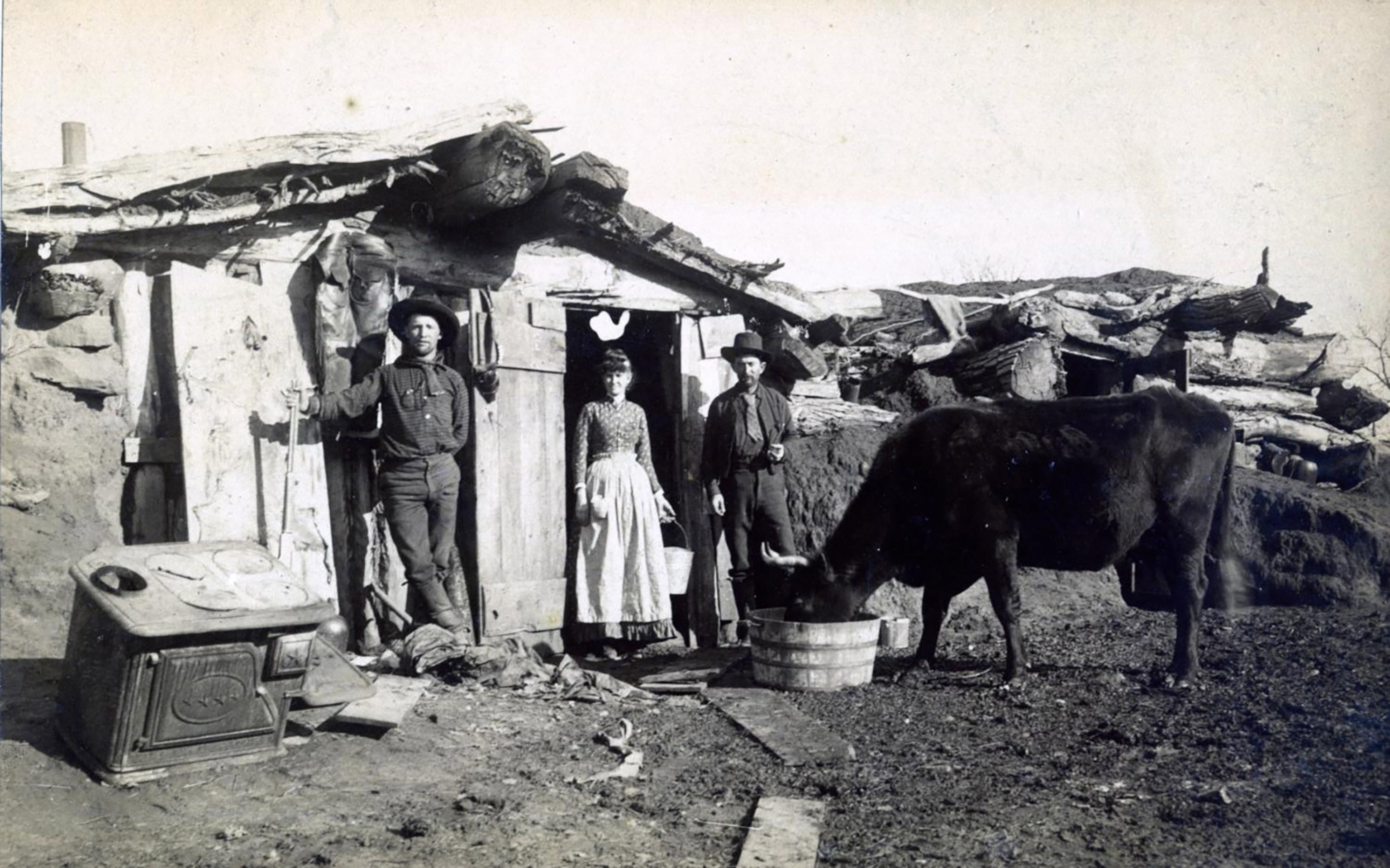

White settlers saw opportunity in the Unassigned Lands. Would-be settlers known as the Boomers squatted on the land and, after years of lobbying, the federal government agreed in 1889 to open it to white settlement.

Fifty thousand white settlers flooded into surrounding areas, waiting for the agreement to go into effect on April 22, 1889. At noon, they surged over the borders to make their claims. In a single day about 11,000 homesteads were claimed. (Some had illegally entered beforehand and were given the nickname “Sooners.”)

(Native American imagery is all around us—while Indigenous people are often forgotten.)

A little more than a year later in 1890, the federal government created Oklahoma Territory from the Unassigned Lands and the western Oklahoma lands.

White settlers were eager to turn the new territory into a state to gain representation in Congress. But both the settlers and Congress were split on how to proceed. Seeing the eventual acquisition of the Five Tribes’ land as a foregone conclusion, they argued about whether Indian Territory should join as part of Oklahoma Territory or as its own separate state.

Sequoyah or Oklahoma?

The federal government cleared the way for statehood in 1898 with the Curtis Act, which announced a plan to abolish tribal governments in eight years, and forced the Five Tribes to accept the allotment law from which they’d been exempt.

Five Tribes leaders realized they would soon have no control or federal recognition. In a last-ditch effort to retain their sovereignty, they held a convention to form a state of their own.

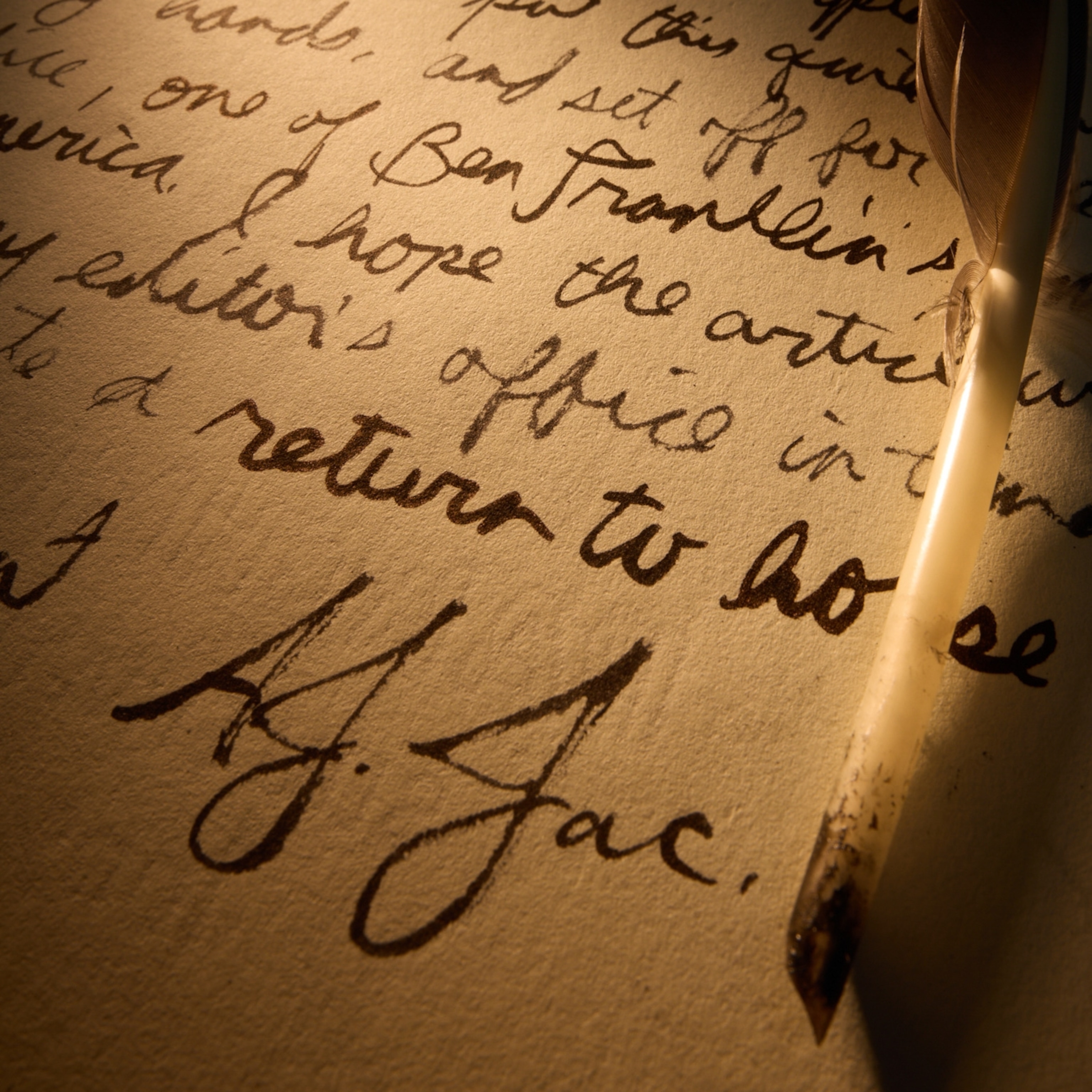

In August and September 1905, delegates drafted a constitution and a proposed government for a Native American-governed state they called Sequoyah. The referendum in Indian Territory passed by an overwhelming margin of both Native and white voters, who at that point outnumbered the territory’s Native residents due to the federal sale of tribes’ “surplus” lands.

(The real story behind the suspicious deaths of more than 60 members of Oklahoma's Osage Nation.)

Yet Congress never voted on the issue. It came down to politics—the Republican-led Congress and Republican President Theodore Roosevelt worried that the state would elect Democratic Senators due to the area’s history of Southern alliances. But as historian Barbara A. Mann notes, Sequoyah was also unpalatable to white lawmakers who desired a state governed by and for white citizens.

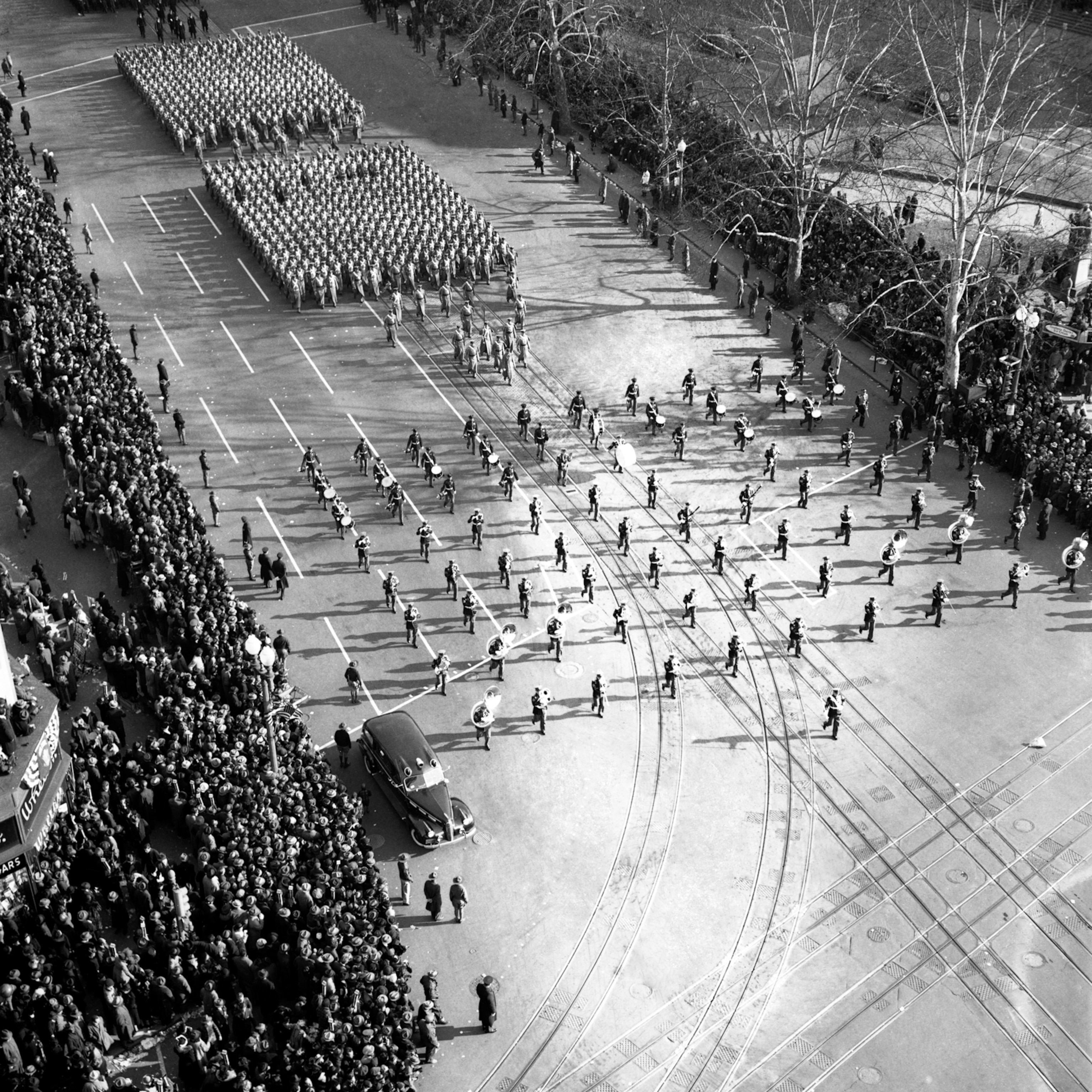

Instead, Congress passed the Oklahoma Enabling Act of 1906. This new law settled the debate over statehood by inviting representatives to move forward with a state that combined both Oklahoma and Indian Territories. On November 16, 1907, Oklahoma became the nation’s 46th state.

The legacy of Indian Territory

Today, more than 13 percent of Oklahomans are Native American, and Oklahoma has the second highest number of Native Americans of any state. But over the years a debate has arisen as to whether the state’s eastern region can still be considered Native land as more and more allotments were sold off by individual Native landowners or seized by the state for the payment of taxes.

In 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court settled the longstanding question when it handed down a ruling in McGirt v. Oklahoma, a case that concerned Jimcy McGirt, a Seminole man whom the state convicted of a sex crime in 1996. His lawyers argued that the state never had jurisdiction to prosecute the crime since it was committed on land promised to the Muscogee in the 1830s. (In the U.S., crimes involving Indigenous people that are committed on Indian reservations are instead subject to federal and tribal jurisdiction.)

The Supreme Court agreed 5-4, a ruling that was hailed as a victory by the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and other tribes as recognition of the land’s reservation status.

(Nat Geo photographers reflect on their heritage as Native Americans.)

The ruling’s reverberations were most immediately felt in federal and tribal courts, where local prosecutors immediately began referring criminal cases related to people of Native American descent. A later ruling clarified that the decision does not apply to non-Native Oklahomans suspected of committing crimes in the former Indian Territory.

“Many folks are in tears,” Jonodev Chaudhuri, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s ambassador, told Indian Country Today after the ruling. “Despite a history of many broken promises, as is true with many tribal nations, the citizens feel uplifted that for once the United States is being held to its promises.”

For many, the ruling is seen as a step toward long-sought Native American sovereignty in Oklahoma—even if the proposed state of Sequoyah never came to fruition.