You can hear the furious roar of drums coming from miles away as cobblestones move slightly out of place beneath your feet. The drumming kids are coming. Let's just hope the century-old buildings of Salvador can withstand yet another parade.

While São Paulo enjoys a reputation as Brazil’s financial engine, and Rio takes the trophy for perhaps the most beautiful city in the world, Bahia is best known for its vibrant culture. One local expression perfectly reflects the artistic verve of Bahians: Here people aren't born, they premiere.

Nowhere is this celebration of culture more evident than Salvador, capital city of the state of Bahia. Something in this place elicits creativity. It might have to do with the fact that, in a city where three out of ten people are unemployed, inventiveness is not a hobby or a choice, but rather a means of surviving one more day. (Discover how dance, food, and music reveal Brazil's African past.)

Across Brazil, cultural expression is a means of protest. Festivals such as carnaval and São João in Bahia, a city known for elaborate celebrations, often expose complex divisions between people from different backgrounds. The country's new far-right political climate has deepened the divide among Brazil's citizens.

More than one-third of the slaves taken from Africa during the slave trade were brought to Brazil to support the sugar economy. Salvador may at times look remarkably Portuguese, but the city’s roots trace back to West Africa. From its overly spicy cuisine to its intoxicating music to its entrancing, dance-filled religious ceremonies, this city is one massive sensorial confusion: after all, is this Portugal or is this Benin?

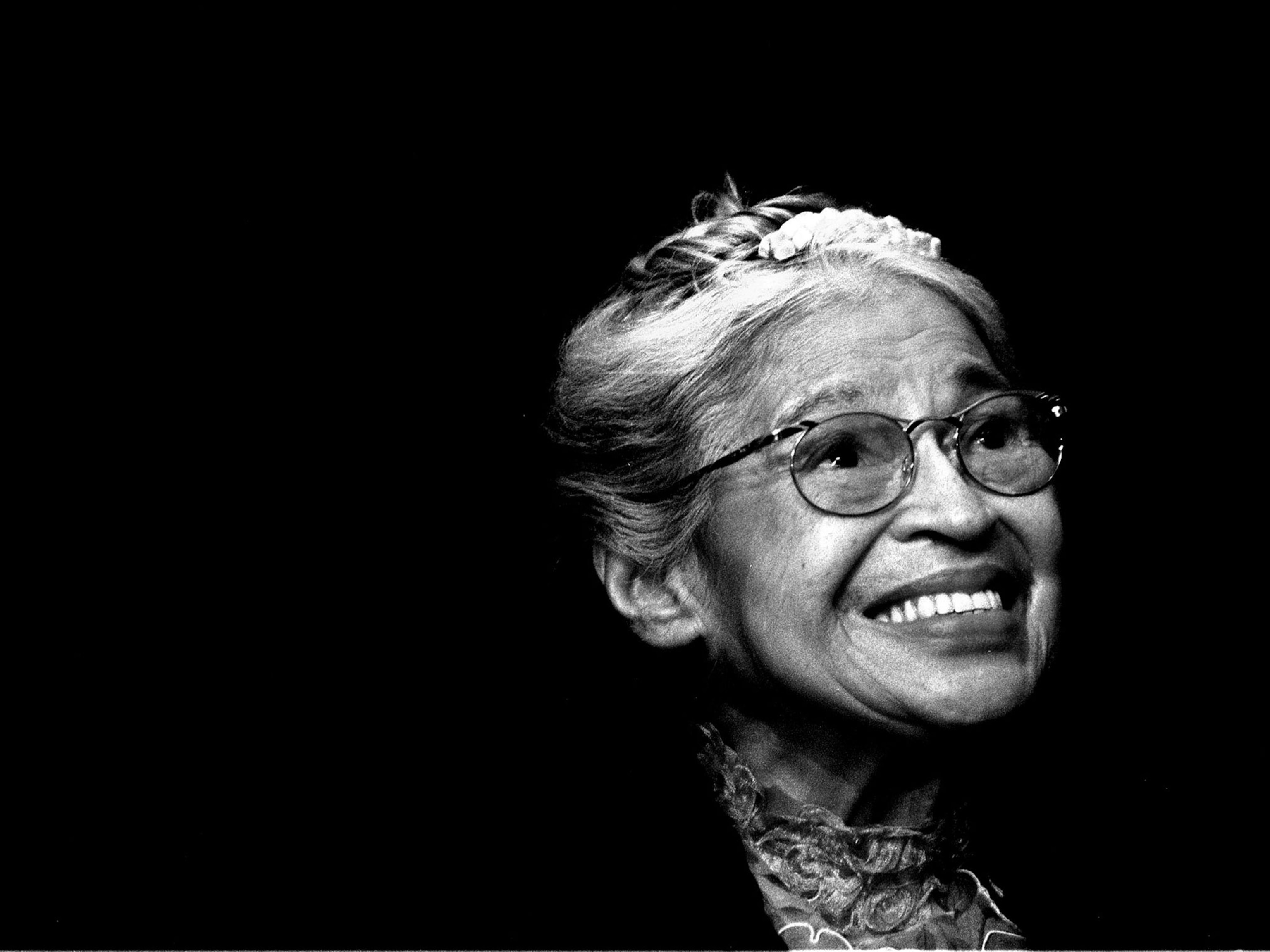

In 1888, Brazil became the last country in the West to abolish slavery, an embarrassing world record few of us are ready to talk about. Perhaps the most blunt conversation starter comes from Salvador, once the largest slave trade port in the Americas, in the unlikely guise of drumming bands. Makes sense if you think about it: try pounding a massive bass drum as hard as you can, and you've got people's attention. The drumming kids draw hundreds of thousands who hear their call for racial equality. (Learn about the thousands of hidden socieites created by escaped slaves in Brazil.)

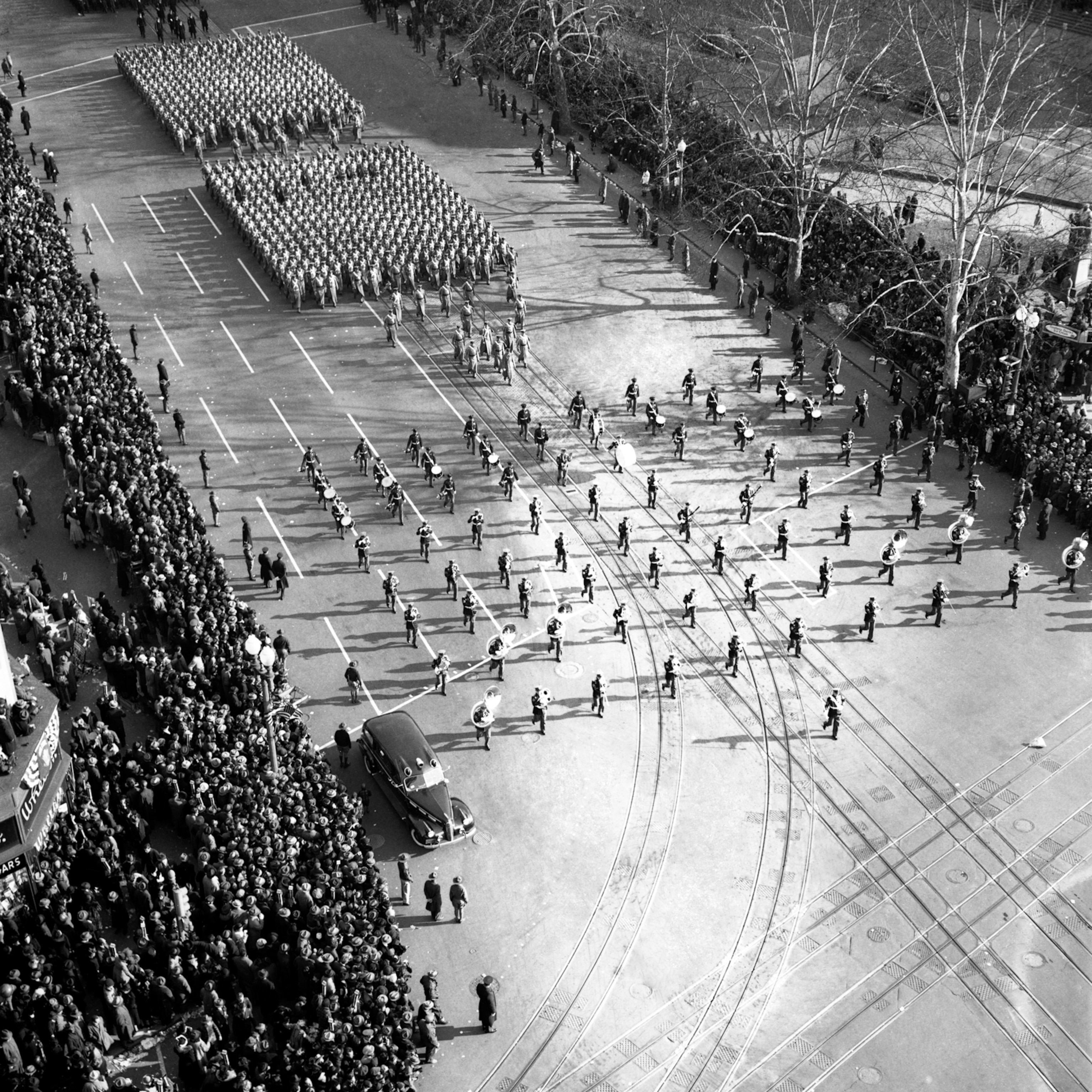

The prevailing beat of Salvador's annual carnaval, which draws nearly one million people, is called samba-reggae, a musical genre sometimes played by ensembles with upwards of 100 drummers. In samba-reggae, the main rhythms of Brazil and Jamaica, which at their root are protest music sung to a cheerful beat, have gained a raw, unadorned, joyful rage.

Bahian carnaval is not all mindless debauchery. Revelers get an unexpected treat. Carnaval is about politics—Brazilian style. Every year, blocos afro—carnaval guilds that strive to advance black culture through music, dance and fashion—traditionally address complex political issues as they parade about in celebration of their African ancestry.

During slavery, an estimated 1.7 million people mostly from present-day Benin were trafficked into Bahia as forced manpower. And the blocos afro don't want people to forget that. Luma Nascimento, an activist and vice chair of one such bloco afro, is well-versed about the intersection between party and politics. "You can see a clear ethnic divide during carnaval," she says. "Those who can afford the expensive camarotes (stands from which attendees watch carnaval parades after paying an entrance fee) are mostly white, while the ones serving them are predominantly people of color."

To voice their discontent about racial inequality and the rise of Brazil's evangelical far-right, agitators like Nascimento and revelers alike chant slogans against the political views they oppose. (See pictures of black joy and resistance from around the world.)

In other parts of the region, people strive to hold on to the culture and traditions they were born into. The further away from Salvador and deeper into the towns and villages of Bahia one goes, the more absurd it seems that this is the same state that hosts the largest street party on the planet. Increasingly deserted, the highways smoothly transition from tarmac to dirt.

In Santiago do Iguape, more than 60 miles west of the capital city, life goes by at a slower pace. "We just want to jump in the river by the end of the day, see the shellfish women at work, look after our elders, and listen on while our men and women sing and talk," says Adinil de Souza, a local community leader. Populated by descendants of runaway slaves, this small village finds no difficulty in keeping things as they have always been.

Since its inception, carnaval celebrations here are ruled mercilessly by a handful of local children who cover themselves with bedsheets and ghastly masks while running around and frightening the evil spirits straight out of town. (Consider the "evil spirits" that haunt the Old Silk Road of Central Asia.)

When asked whether the evil spirits would be the manifestation of ancient slave owners, locals prefer not to delve much. "I wouldn't know about that," de Souza says.

By day's end everyone in Santiago do Iguape is tucked in—the imposing Paraguaçu River ensures abundance to the fishermen who brave its mighty waters in the wee small hours. (See pictures of carnivals and other masquerade celebrations throughout the Americas.)