What we do—and don’t—know about the mysterious illness in the DRC

The unidentified ailment has sickened 1,300 people and led to more than 50 deaths. Regardless of the cause, experts say containing the outbreak will be challenging.

Over the past month, an unidentified illness has sickened more than 1,300 people and led to more than 50 deaths in the northwestern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

The exact cause of the outbreak is still unknown, although the World Health Organization hypothesizes it could be some combination of chemical poisoning, meningitis, malaria, and other infections. The situation is concerning because, according to the WHO, the number of people affected nearly doubled over the course of the last week of February. “If we see these numbers continue to jump unabated, that’s a major red flag,” says Lauren Sauer, a Baltimore-based outbreak response expert at the National Emerging Special Pathogens Training and Education Center. She’s also worried that tests haven’t yet identified a consistent pattern to explain the cases.

We’ll learn more in the coming days and weeks. Meanwhile, here’s how experts are thinking about the situation, and how they plan to figure out what’s going on.

The illness looks a lot like many other illness

One of the biggest questions both experts and the public have right now is: What's causing these illnesses?

According to the WHO, symptoms of the illness may include fever, headache, chills, sweating, stiff neck, body aches, runny or bleeding nose, cough, vomiting, and diarrhea. That's a broad list that could be attributable to many infections, including malaria, meningitis, and viral infections like Ebola. People with illnesses related to non-infectious causes – like toxins – could also have many of these symptoms. But testing to date has been inconclusive.

(Should you get a measles booster? Some people may not be as protected as they think.)

The answer to “what’s causing the illness?” determines who's at risk, what treatment they need, and what steps must be taken to prevent the outbreak from spreading beyond its current borders, says Neil Vora, a physician and senior advisor for Conservation International, a non-profit organization focused on preserving the world’s biodiversity in nature.

Option 1: It could be a poisoned water source

At a briefing on February 28, WHO director of emergencies Michael Ryan said that while authorities were still looking for infectious causes, they had a “strong level of suspicion” that some cases were related to a poisoned water source. For example, if an outbreak is caused by a toxin, authorities would focus on identifying its source, preventing people’s exposure to it, and ensuring it doesn’t happen again. The risk to people outside the outbreak area would vary depending on its source, but when cases are closely associated with a local water source – as many in this outbreak appear to be – containing it is relatively straightforward.

Option 2: Meningitis or malaria

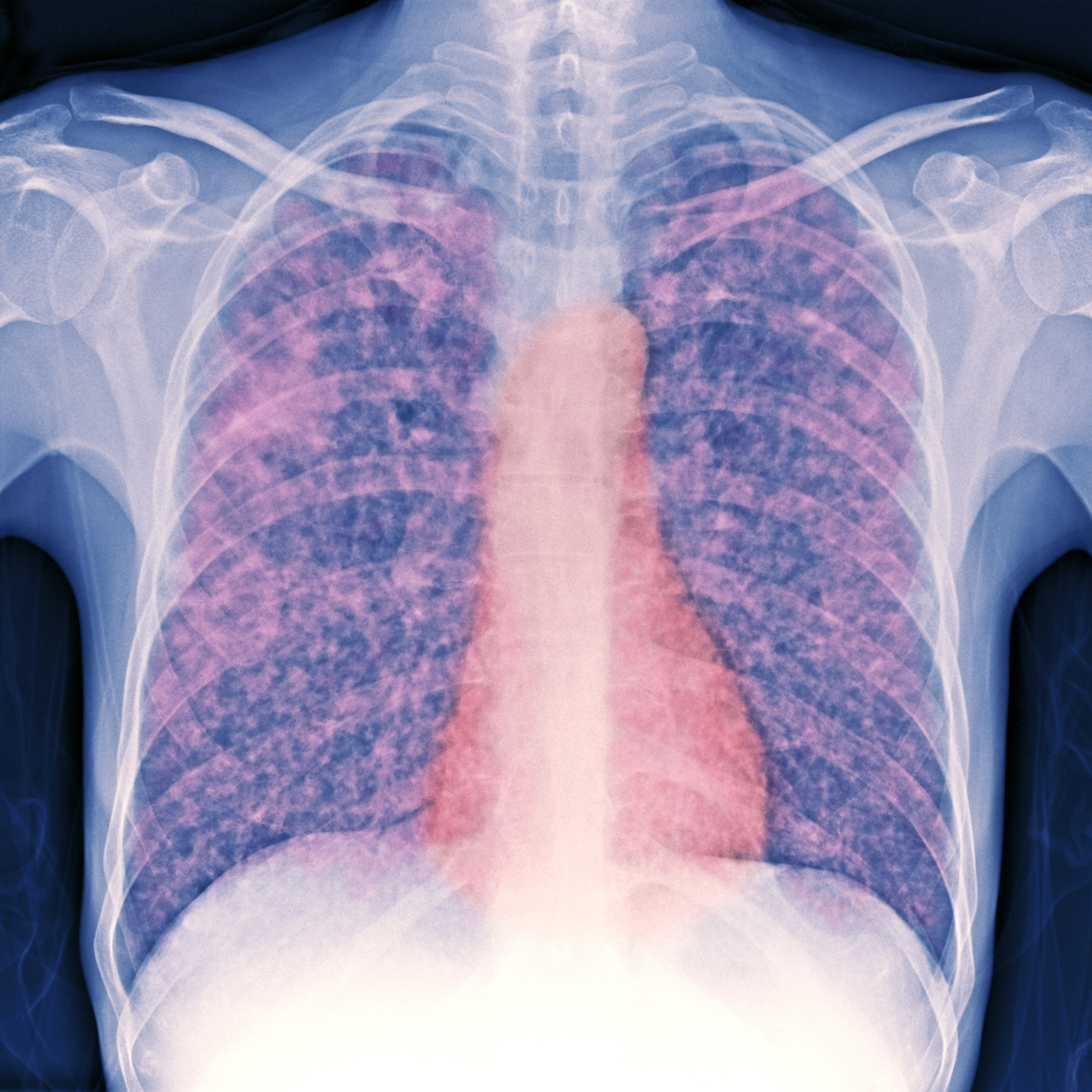

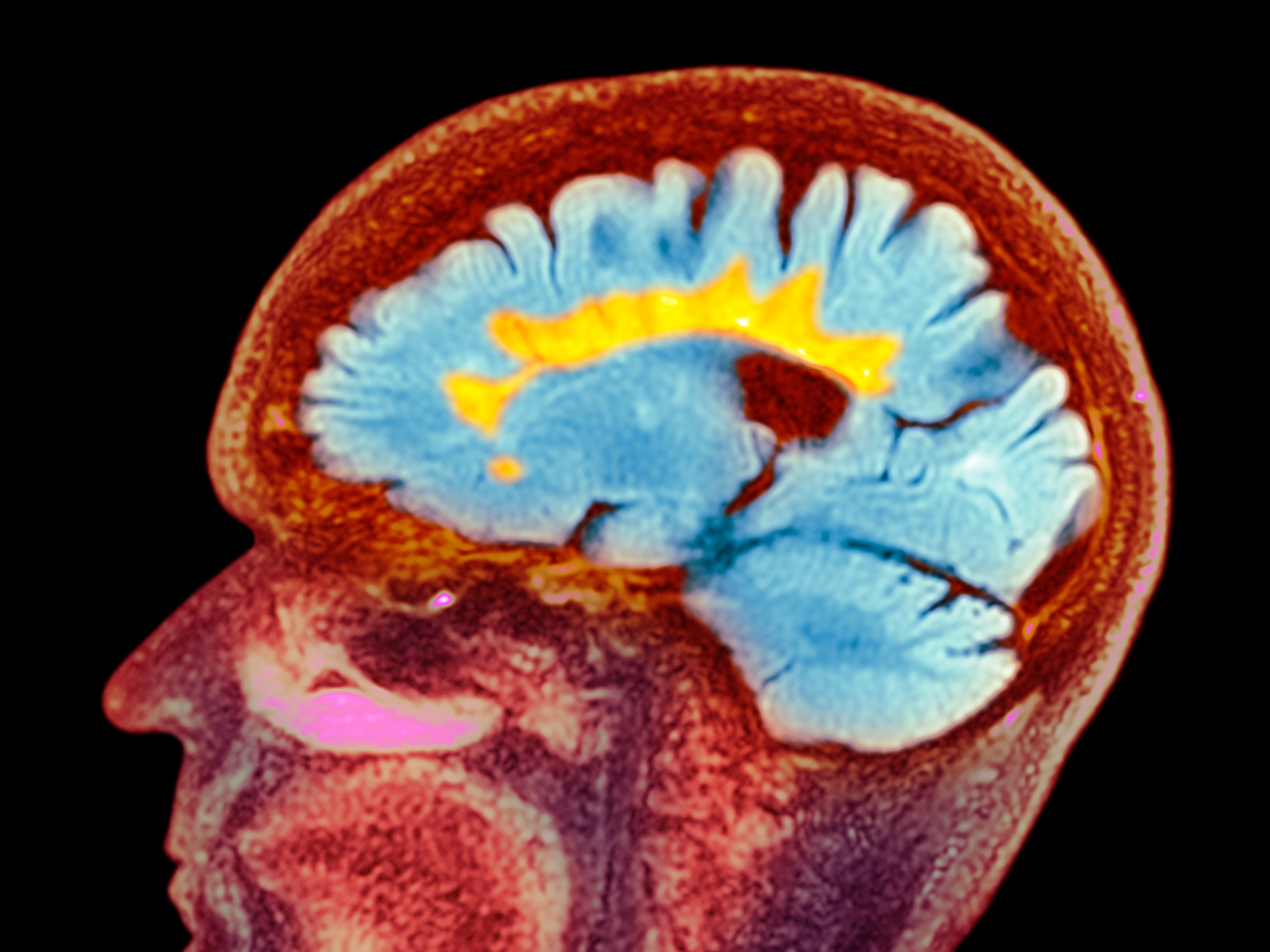

It’s also possible the outbreak is caused by malaria or a bacterial form of meningitis, an infection of the tissue that surrounds the brain and spinal cord.

Certain types of bacterial meningitis progress from symptoms to death very quickly, and spread through coughing or contact with other people’s saliva. Infections can be curtailed by preventing that contact, and also by giving exposed people a protective course of certain antibiotics; vaccination also prevents the spread of this disease.

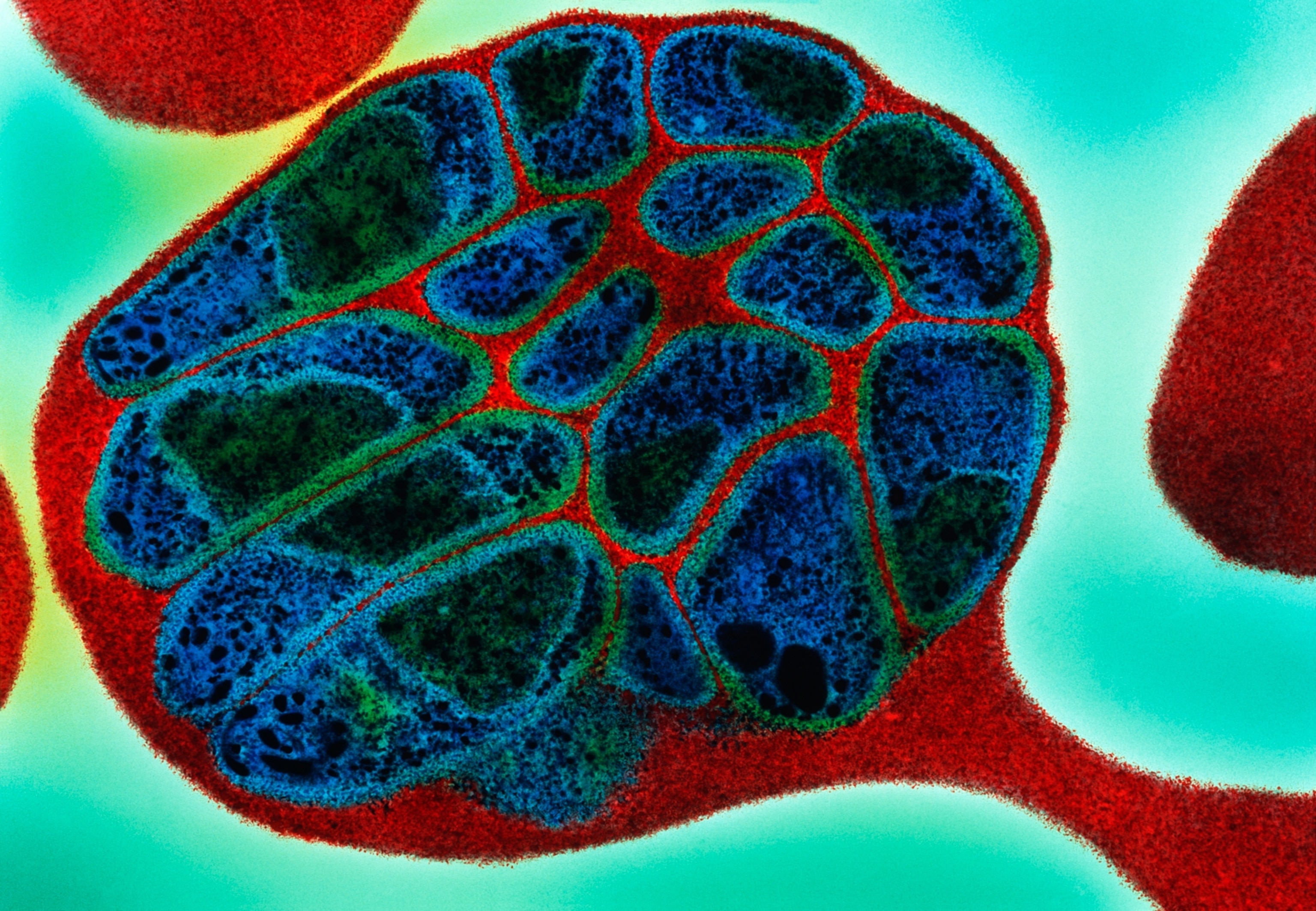

Malaria is also a prime suspect. The Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said between 55 and 78 percent of samples from patients involved in the outbreak had tested positive for malaria. But these results alone aren’t proof of a causal relationship because that mosquito-borne infection is so common at baseline in the region. That is: people could test positive for malaria, but still be intensely sick for a different reason.

If it does turn out to be malaria – which is spread by Anopheles mosquitoes – there’s a well worn playbook to follow, including treating local people with malaria medicines and preventing bites with bed nets and other anti-mosquito precautions. For example, a few months ago, a separate outbreak leading to nearly 900 illnesses and 48 deaths, most of them in young children, sprang up in a different region of the DRC. That outbreak was ultimately linked to a wave of malaria, which was compounded by acute malnutrition and a spate of respiratory viruses. Health authorities curbed that surge in cases by directing extra medicines and other medical supplies to the area, and sending public health experts to support early case-finding efforts in the region.

If this current outbreak is attributable largely to malaria, then there are less worries about the situation fueling a larger epidemic, as the threat to people outside areas where these mosquitoes live is low.

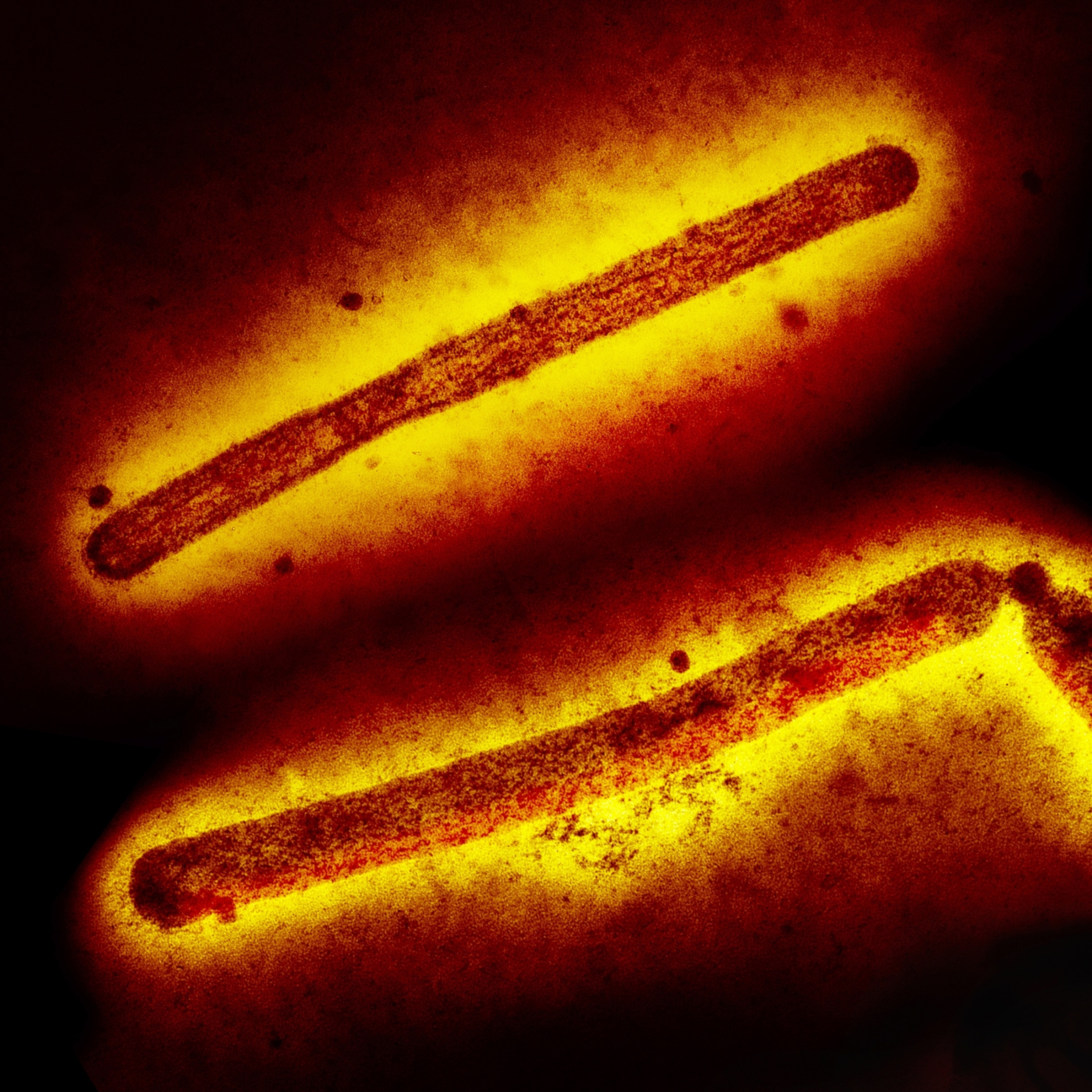

Option 3: A hemorrhagic fever like Ebola

If the outbreak is caused by a viral hemorrhagic fever like Ebola, which spreads from person to person via contact with infected bodily fluids, controlling it will require many more resources, including equipment allowing clinicians to provide intensive care-level treatment to patients while also protecting themselves. The response would also require a lot of people to conduct contact tracing and, if Ebola is the culprit, could involve vaccinating infected people’s close contacts. Additionally, because these viruses spread from person to person, there would be a greater chance the infection could spread outside the region where it starts.

The hemorrhagic fever scenario would be more concerning. Between 2014 and 2016, Ebola killed 11,000 people across Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone in the largest outbreak of that infection on record; another large outbreak in the DRC led to nearly 2,300 deaths between 2018 and 2020. Multiple smaller outbreaks of related viruses sporadically erupt across the continent, including two active outbreaks in Tanzania and Uganda, the latter of which recently claimed the life of a four-year-old boy. Still, the toolkit for responding to these outbreaks has come a long way: new vaccines – which may soon include one being trialed in Uganda – have dramatically reduced the risk of death due to Ebola infection.

(This is the worst flu season in 15 years. Here's why—and how to protect yourself.)

Gathering information about what people ate, drank, and did before getting sick is a good way to generate ideas for what’s causing any outbreak – and that effort is under way in the DRC. The first people involved in the outbreak had reportedly eaten meat from wild bats, which has raised some concern that a hemorrhagic fever virus, endemic in some of these creatures could be the cause of the outbreak.

More definitive information comes from testing samples from affected patients, along with samples from their food, water, and environment. Although it’s unclear yet whether spillover caused the current outbreak, moments like this are reminders to Vora that the human threat to ecosystem health ultimately circles back to hurt us. Deforestation and conflict create more opportunities for people to interact with stressed, sickened animals, increasing the risk we’ll share their diseases. “We live in an interconnected world,” says Vora. “The health of humans depends on the health of animals – and also, nature.”

There are many other possible causes of this outbreak, including the possibility of multiple intersecting health problems exacerbated by social upheaval and geographic isolation. That has its own unique dangers, says Ryan: the global community is often “very concerned about these events” until the cause proves to be a combination of familiar culprits, he said at last week’s briefing. “And once we establish that it's not some major new Earth-killing virus, we all lose interest.”

The response will be difficult

Regardless of the cause, the situation might be difficult to resolve.

It’s taking place in a remote area of a country currently suffering through active armed conflict. That likely creates obstacles for local and international aid workers helping with the response, and it also makes it challenging for the DRC’s Ministry of Health to get and share real-time information with its international partners. The country is facing multiple crises simultaneously, including a massive mpox outbreak and internal displacement due to an uptick in intense armed conflict.

The outbreak also coincides with the early days of the Trump administration in the U.S., which poses some additional challenges. In any new administration, it takes time to get staff in the right places to do all the information-sharing that’s necessary to keep all systems going, says Sauer.

But compounding that challenge: recent cutbacks in the U.S.’s global health footprint. Under normal circumstances, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) staff would be in close contact with the DRC’s health ministry and other partners, and would help provide supplies and other assistance with an investigation based on the country’s needs. Other doctors and scientists would also be receiving regular updates about the situation from the WHO and from the DRC’s health ministries.

However, many USAID staff were removed from their posts in the DRC as part of the new administration’s effort to dismantle the agency. And in January, the Trump administration issued an executive order requiring CDC to cease collaboration with the WHO. That means the U.S. doesn’t have eyes and ears on this threat, and may be unable to offer meaningful support.

These changes hinder the DRC’s ability to contain an outbreak – and they could increase the danger in other countries if this is a communicable disease. The U.S.’s readiness to respond to an outbreak that spreads stateside is directly related to whether it’s getting reliable information about what’s happening overseas. “We make decisions about resources and staffing and things like that based on that information flow,” Sauer says. High-quality, real-time outbreak data is critical for ensuring airports have enough staff to screen travelers from affected countries, and ensuring specialized regional medical centers have enough doctors and nurses to care for any affected people.

This outbreak should remind us that germs don’t care about changes in local or international politics – and that preparing for their possible spread is an ongoing job, says Sauer. “Pathogens are smart, and they figure out how to be outbreaks,” she says, “so we have to remain vigilant.”