Faith fills more than a spiritual void for California’s migrant workers

The church has long played a role in the fight for justice for farmworkers. Although today, as photographer Brian L. Frank shows, it looks a little bit different.

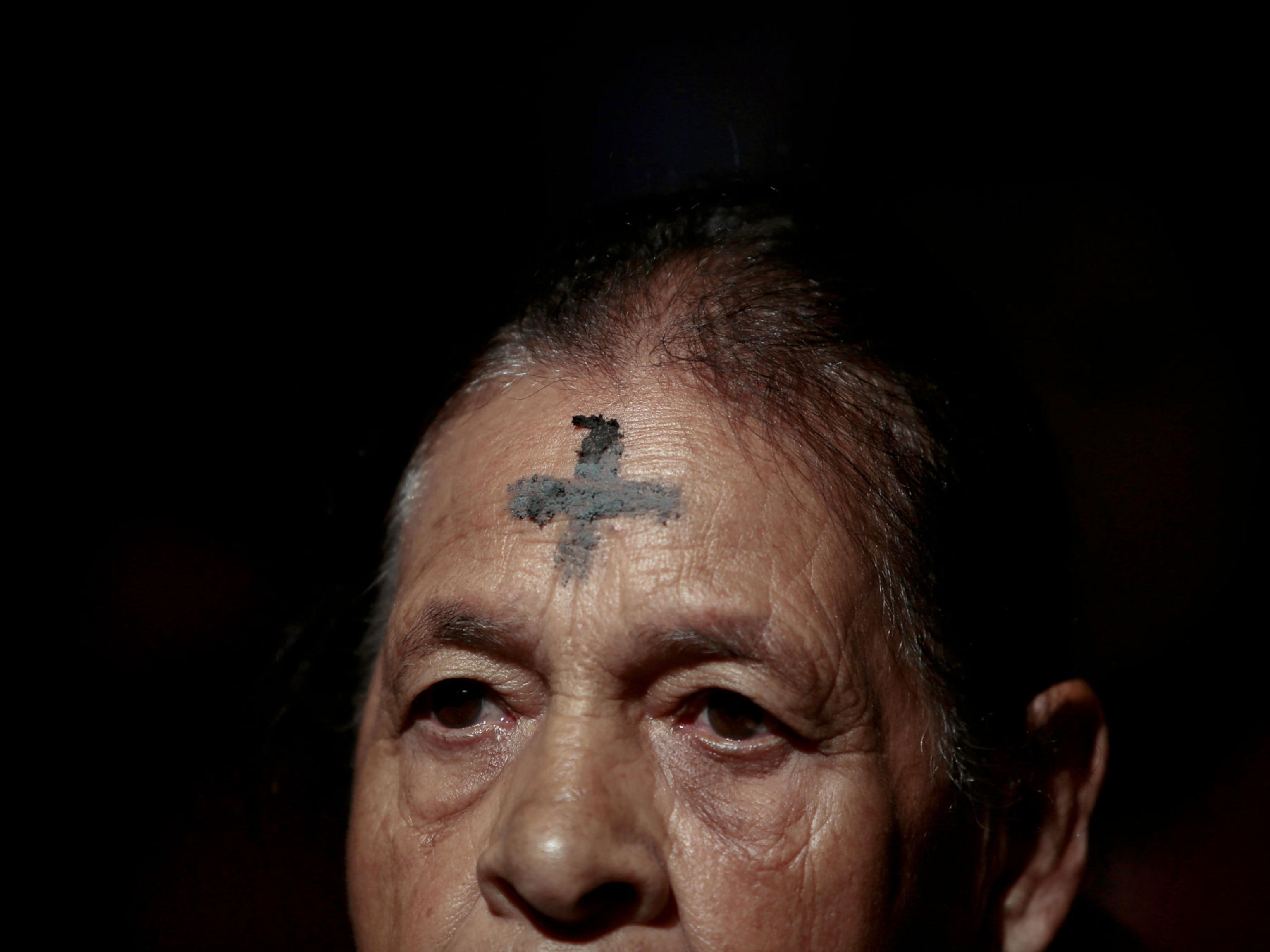

Faith and farmworkers have long been pillars of life in California’s Central Valley—intertwined in a fight for justice.

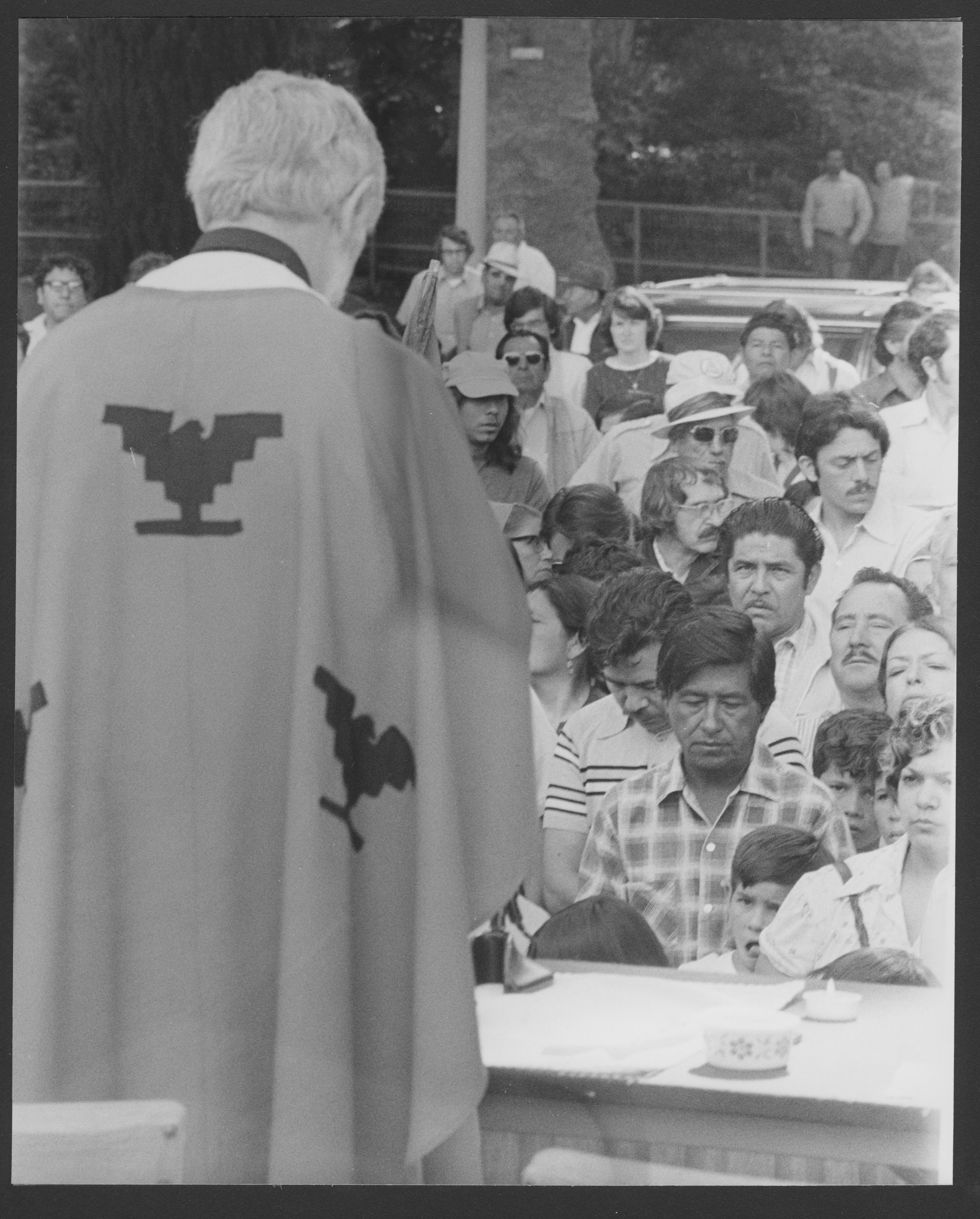

You can see it throughout the story of César Chávez, the civil rights leader and devout Catholic who sought better wages and working conditions for Mexican migrants in the 1960s. Chávez infused the movement with religious teachings of nonviolence and ministry to the poor, and even rallied the Catholic Church to support La Causa.

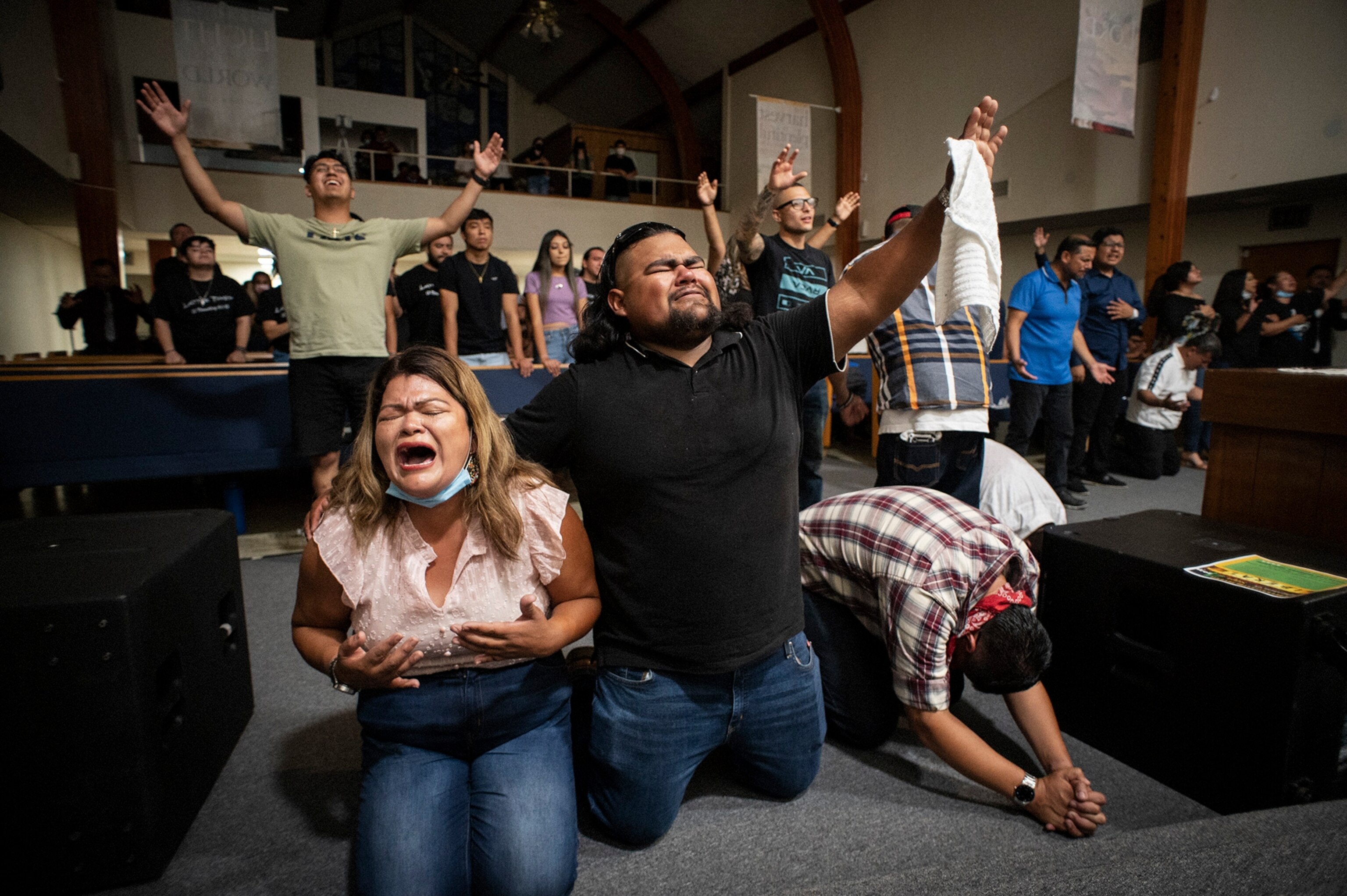

Today, faith still plays a key role—although photographer Brian L. Frank shows in this photo essay that it looks a little bit different.

Catholic priests are still preaching in the fields but instead of Spanish they’re learning Indigenous languages to serve their congregations who have migrated from farther south in Latin America. And ministry is no longer dominated by Catholics either, as evangelical churches expand their reach.

Faith has become even more important in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, which laid bare the inequities migrant workers face. As most Americans took refuge in their homes, migrants continued to farm the nation’s food. Fearing deportation, they turned to the church—not government—for help with child care and healthcare.

Here’s a glimpse of life in the Central Valley.

This is one of eight stories from The Past Is Present project, a collaboration between National Geographic and For Freedoms.

READ THIS NEXT

These Chinese immigrants opened the doors to the American West by Phillip Cheung

How Puerto Rico is grappling with its past—to reshape its future by Christopher Gregory Rivera

How has Texas changed in 20 years? She went home to find out by Tanya Habjouqa

Honoring the sacred places they were forced to leave behind by Dakota Mace

‘They emanate light’: Illuminating the lives of Mexico’s Indigenous people by Yael Martínez

These Black transgender activists are fighting to ‘simply be’ by Joshua Rashaad McFadden