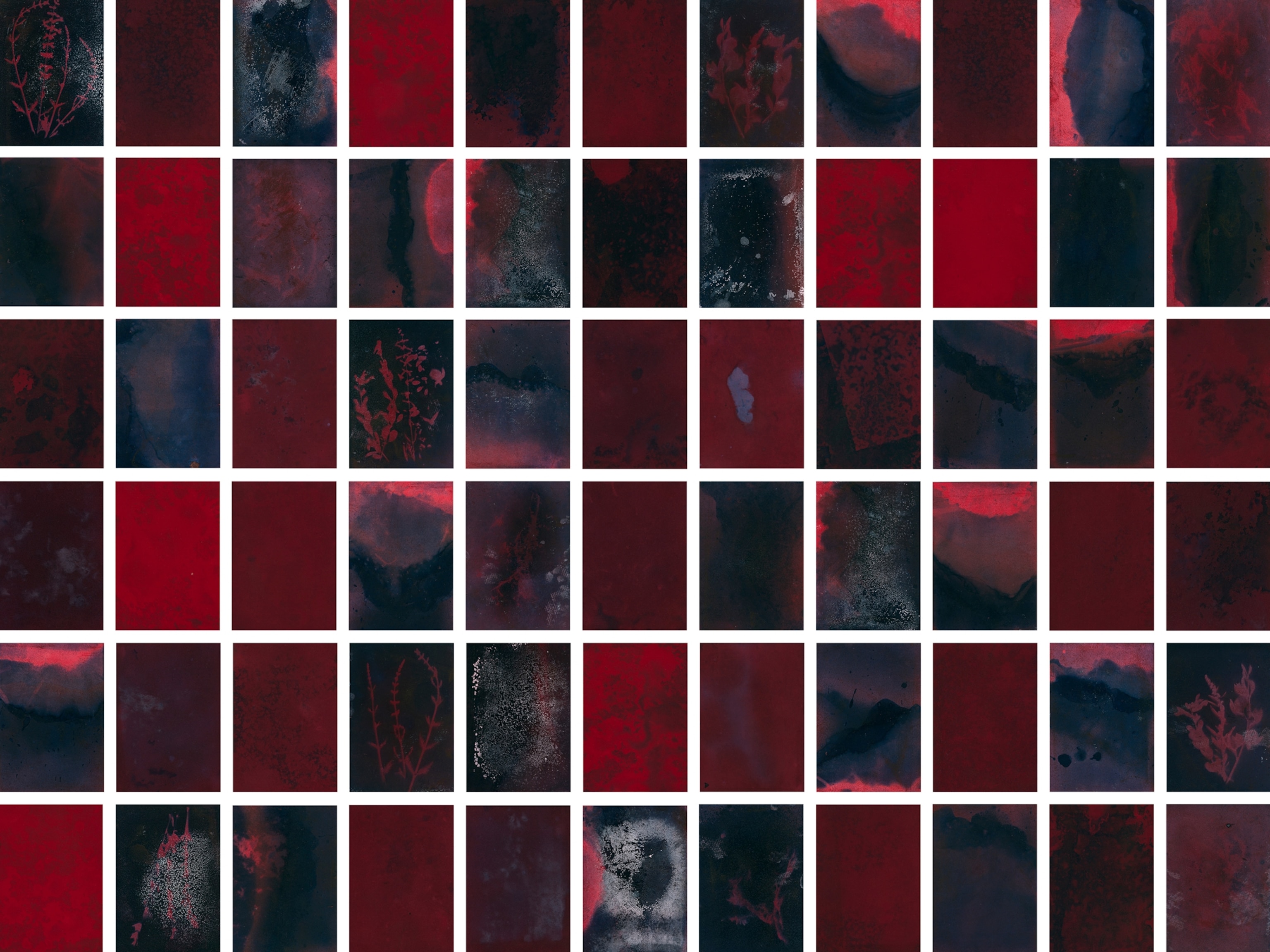

Honoring the sacred places they were forced to leave behind

After the U.S. seized their lands more than 150 years ago, the Diné (Navajo) people embarked on the Long Walk—a 300-mile trek to exile. Photographer Dakota Mace shares their stories.

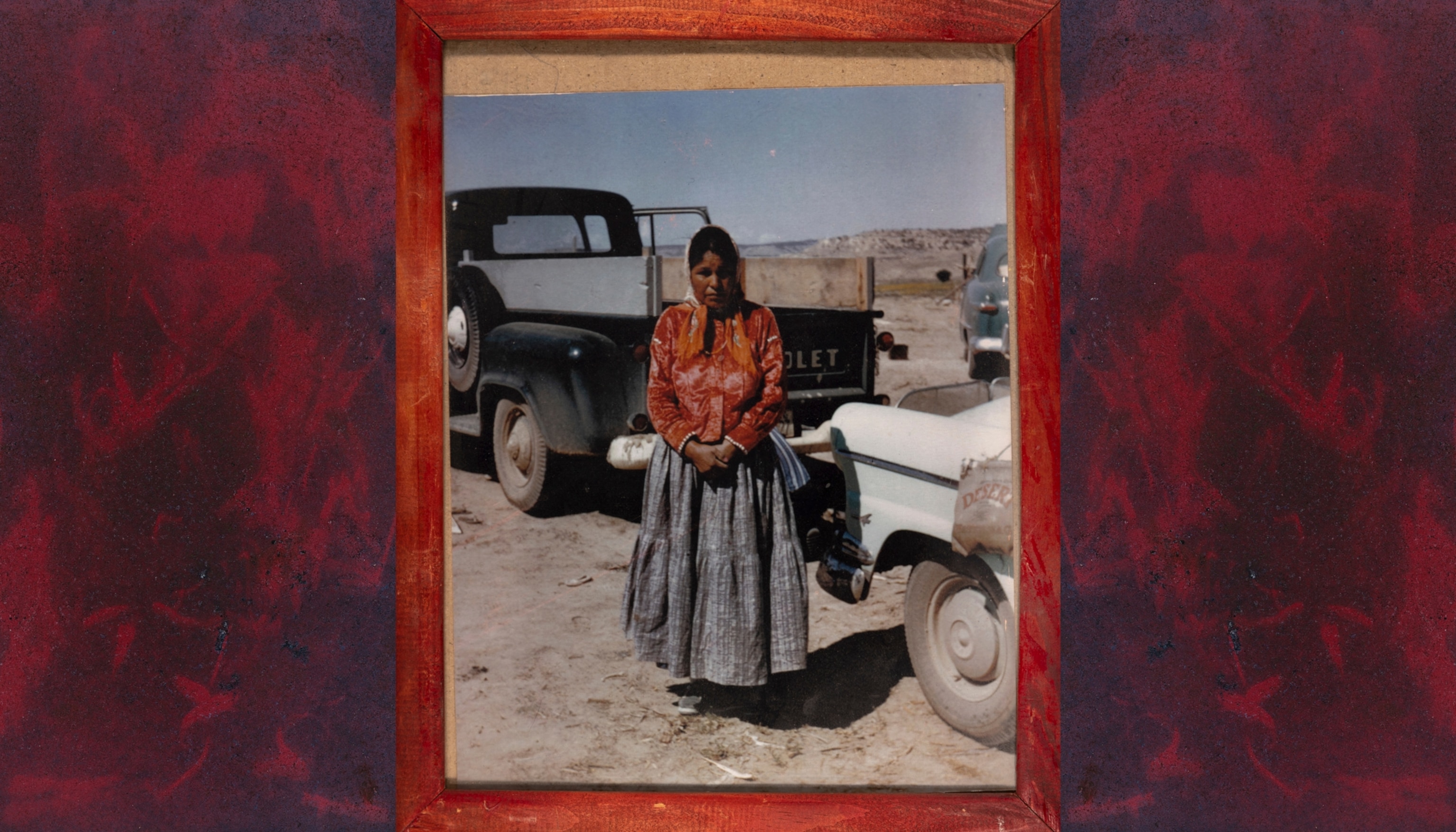

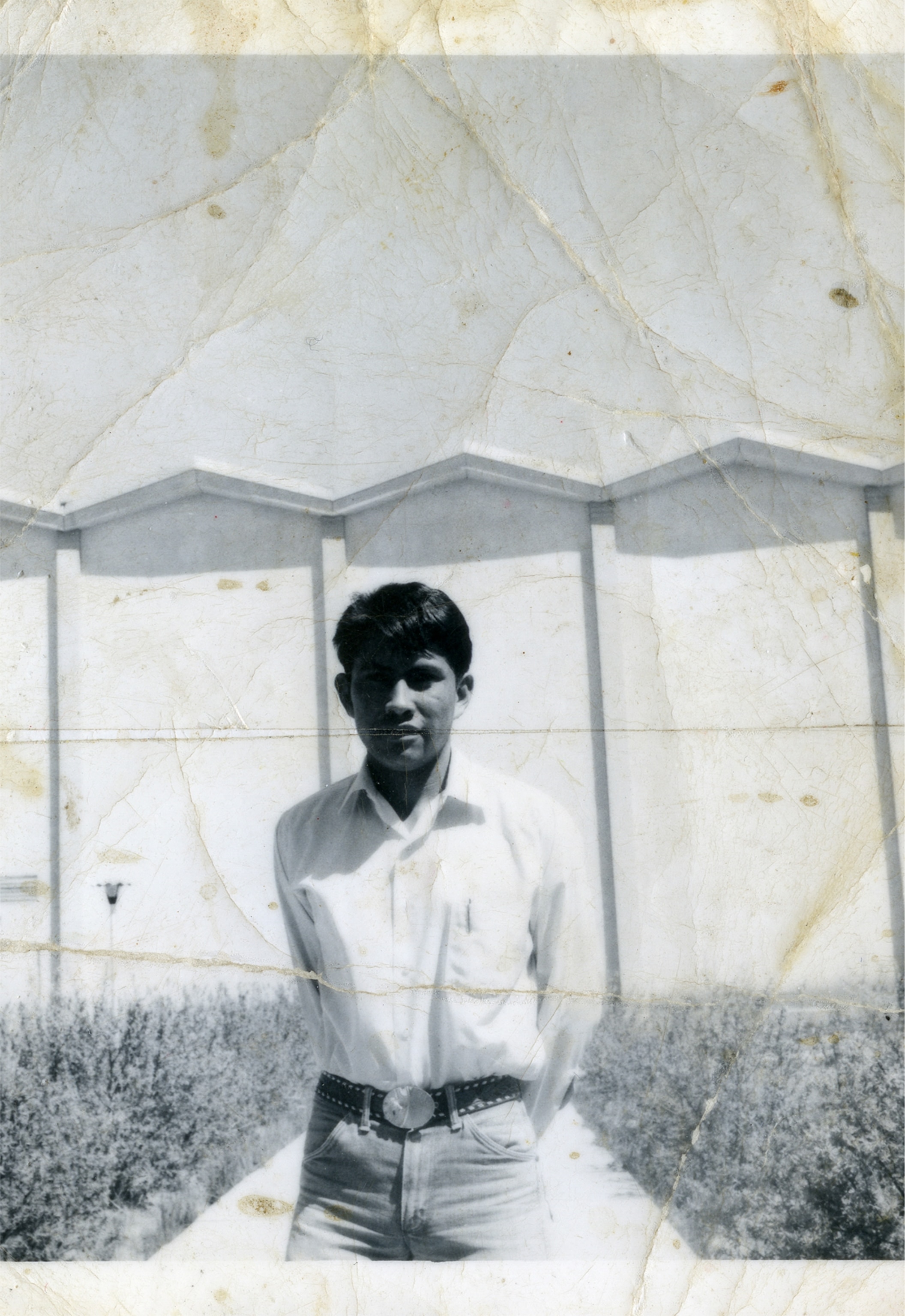

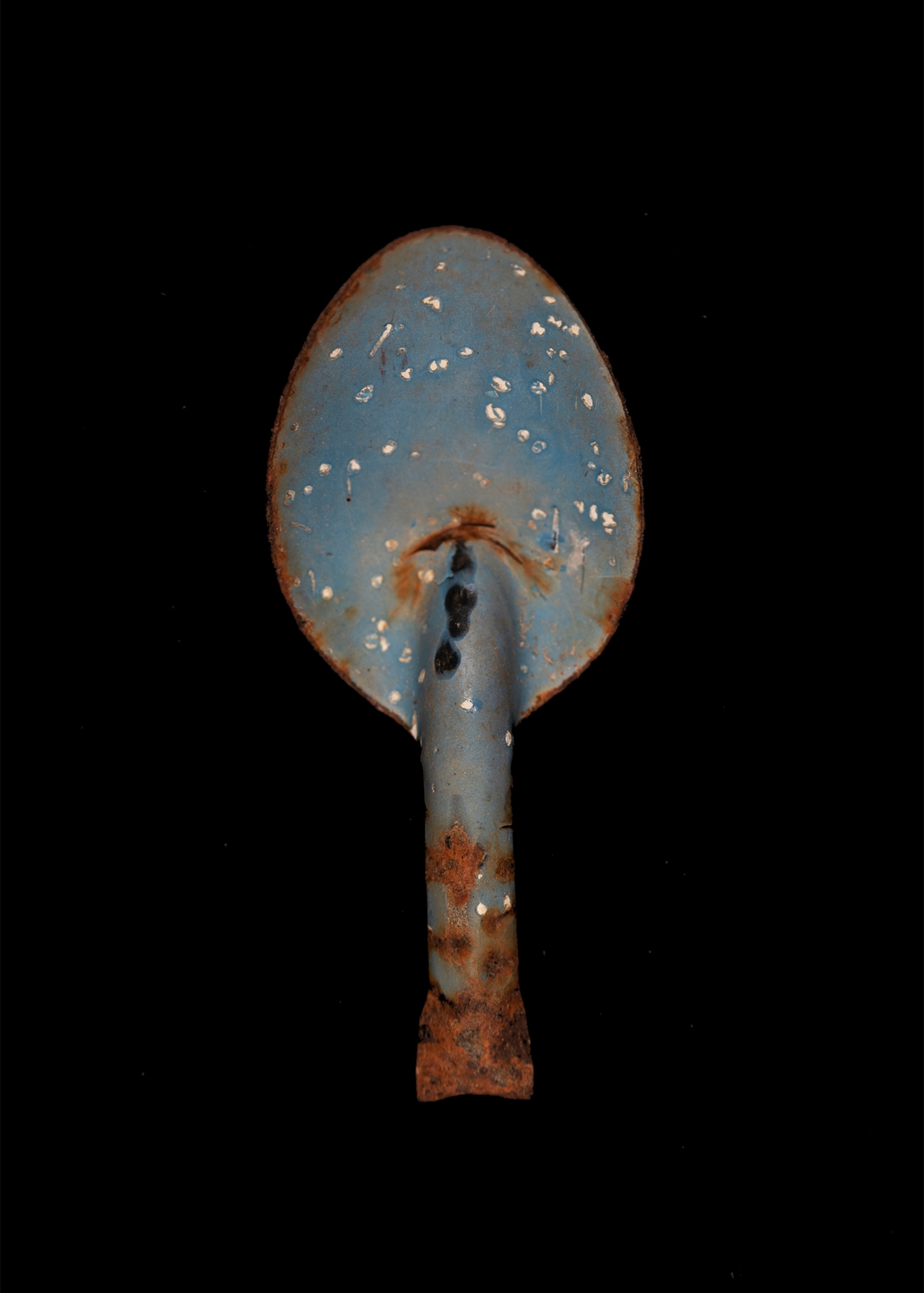

It happened more than 150 years ago. But the memory of the Long Walk—the forced exile of the Diné (Navajo) people—still lingers on the landscape of the American Southwest.

Beginning in 1864, more than 8,500 men, women, and children took the arduous wintertime trek across more than 300 miles from their lands in northeastern Arizona and northwestern New Mexico to an internment camp in eastern New Mexico. Some 200 people died along the way, from starvation, exposure, and violence at the hands of the U.S. military personnel who had evicted them from their homelands.

Those who survived endured miserable conditions at the Bosque Redondo Reservation, where they were ravaged by disease, hunger, and cold, and prohibited from singing or praying in their native language.

The Long Walk may be part of our past—but “it is still with us, and we must remember what happened,” writes Diné photographer Dakota Mace in a presentation of this photo essay. “This moment in our history defined a new era of sovereignty, one of resilience and survival, and reminds us of the struggles for the rights of our land, natural resources, and freedom.”

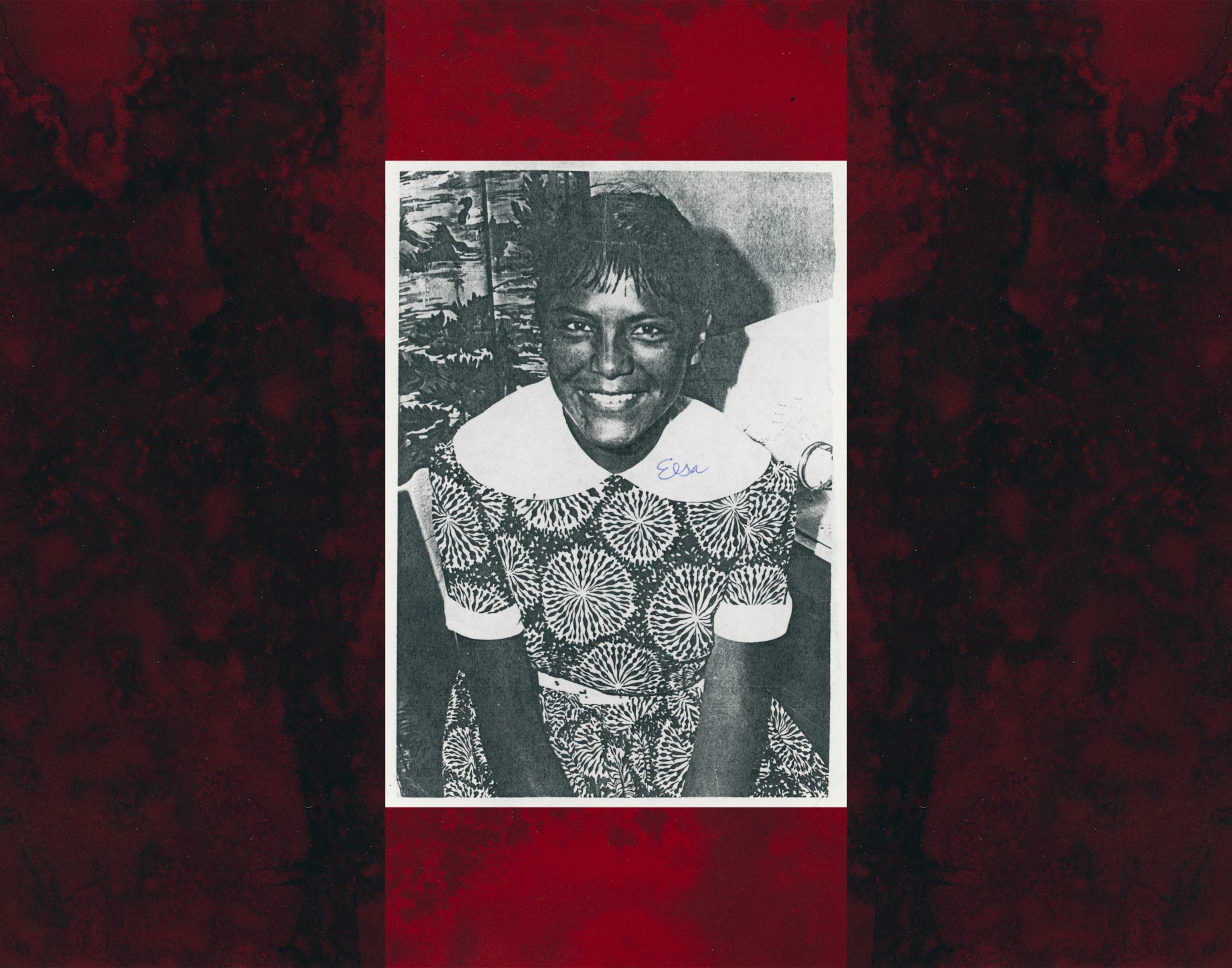

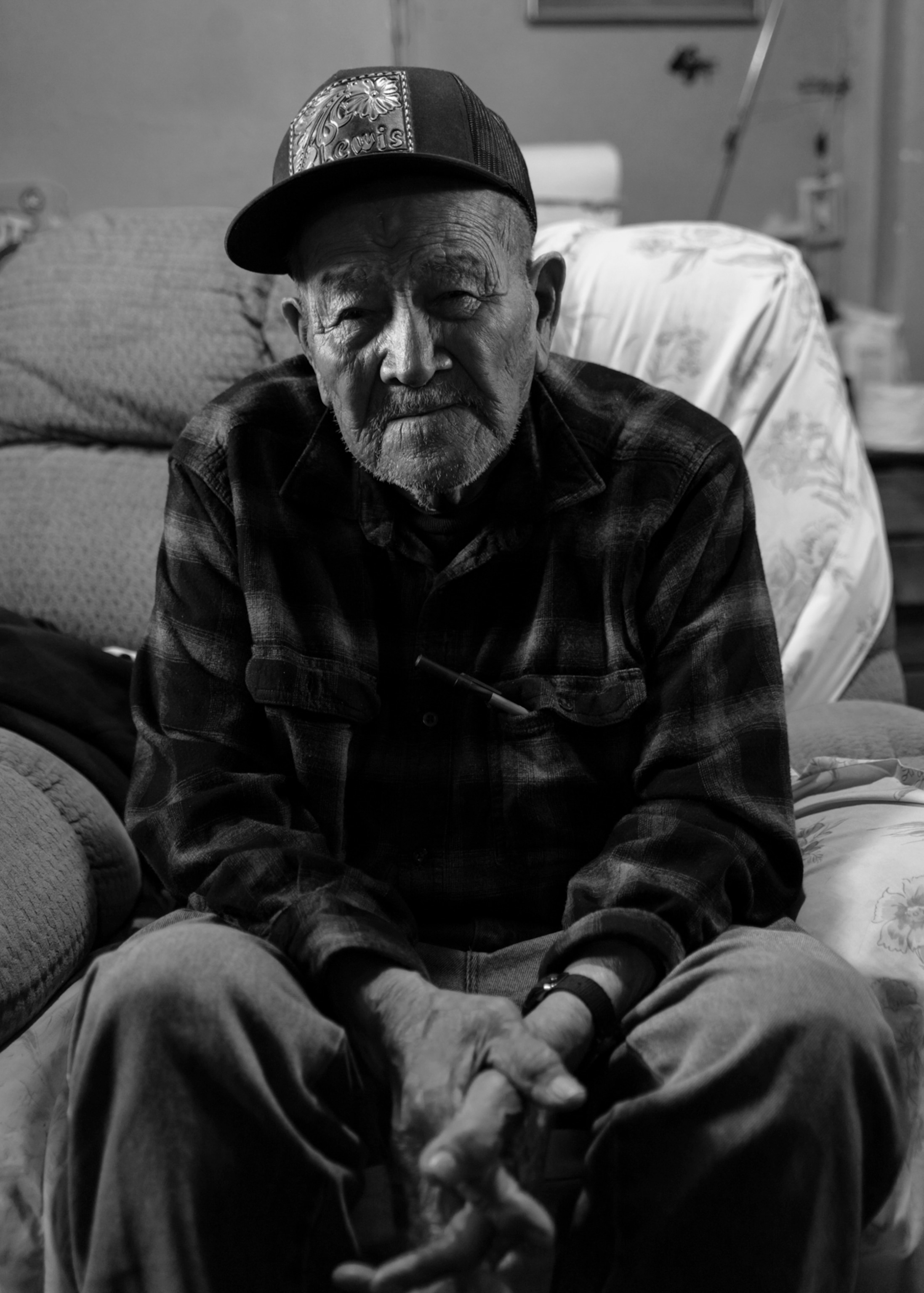

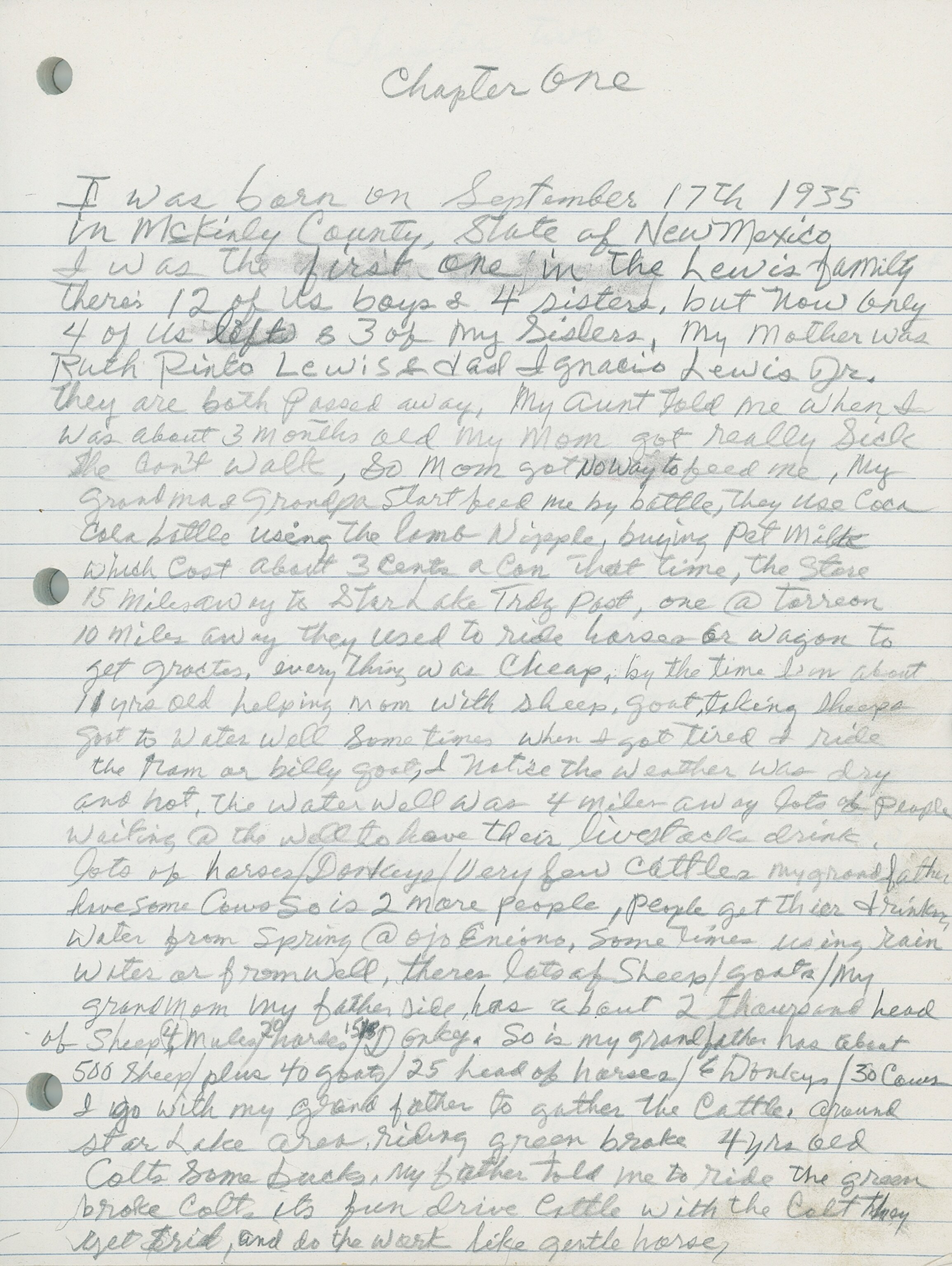

Seldom mentioned in U.S. history books, few stories of the Long Walk remain, passed down through Diné elders. Through the lens of her camera, Mace seeks to take back the memories of her ancestors and explore the narratives of this sacred land.

This is one of eight stories from The Past Is Present project, a collaboration between National Geographic and For Freedoms.

READ THIS NEXT

These Chinese immigrants opened the doors to the American West by Phillip Cheung

Faith fills more than a spiritual void for California’s migrant workers by Brian L. Frank

How Puerto Rico is grappling with its past—to reshape its future by Christopher Gregory Rivera

How has Texas changed in 20 years? She went home to find out by Tanya Habjouqa

‘They emanate light’: Illuminating the lives of Mexico’s Indigenous people by Yael Martínez

These Black transgender activists are fighting to ‘simply be’ by Joshua Rashaad McFadden