How Puerto Rico is grappling with its past—to reshape its future

In a land shaped by colonialism, photographer Christopher Gregory Rivera hopes to foster a “better understanding of where we are and who we are—and where we could possibly go.”

That beach with a tank, Flamenco, has been named one of the top 10 beaches in the world. I’m Puerto Rican, and by photographing it like this, I’m trying to make a point. This place that is beautiful—and enjoyable, and a tourist destination—has a complicated history that’s important to understand, for both visitors and locals. When I was a child in San Juan schools, a lot of our story was glossed over: The islands were “discovered” by Christopher Columbus, the Taíno Indians were decimated, the U.S. “happened” into possession of it, Puerto Ricans were made U.S. citizens in 1917, in 1951 there was a referendum, our constitution was written, we lived happily ever after. You know? It wasn’t until I began to learn more deeply about these episodes that many of the injustices I was seeing, in the present, started to make sense.

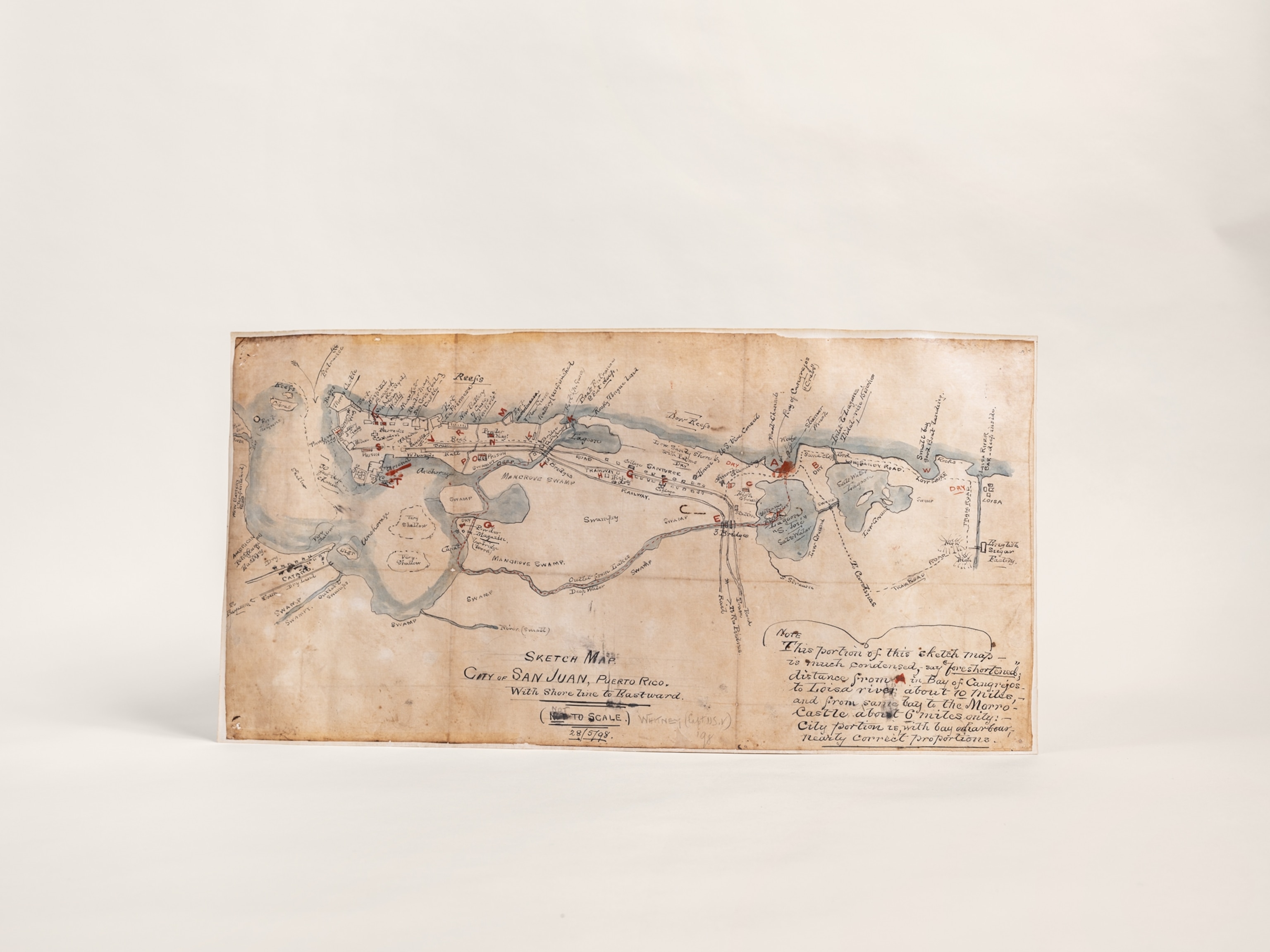

Puerto Rico is considered the world’s oldest colony. The legal word for our status is “territory,” but this is a land completely shaped by colonialism and conflict. It will take years to finish removing the unexploded ordnance on Vieques and Culebra islands, from the decades of U.S. military testing. To this day, divorcing yourself from that reality does a disservice to the people who live here. Except for the Taíno, we’ve never known existing without a foreign power ultimately in control—we are citizens, yes, but without full political rights—and we’re grappling with this history now. There’s much discussion about the political future of Puerto Rico, the current austerity measures that Puerto Ricans basically have no vote on, and the gentrification and displacement, especially since the pandemic. A lot of my work is to educate people and unlock a better understanding of where we are and who we are—and where we could possibly go.

This story appears in the August 2023 issue of National Geographic magazine and is one of eight stories from The Past Is Present project, a collaboration between National Geographic and For Freedoms.

READ THIS NEXT

These Chinese immigrants opened the doors to the American West by Phillip Cheung

Faith fills more than a spiritual void for California’s migrant workers by Brian L. Frank

How has Texas changed in 20 years? She went home to find out by Tanya Habjouqa

Honoring the sacred places they were forced to leave behind by Dakota Mace

‘They emanate light’: Illuminating the lives of Mexico’s Indigenous people by Yael Martínez

These Black transgender activists are fighting to ‘simply be’ by Joshua Rashaad McFadden