‘They emanate light’: Illuminating the lives of Mexico’s Indigenous people

Using a special technique, a photographer makes luminous images of Mexico’s comunidades originarias.

When Yael Martínez asked her please to gaze directly into his camera, Joséfina Prudente Castañeda was at the Brooklyn church she uses as a recording studio. She migrated north from the Mexican state of Guerrero and now broadcasts, to New York and beyond, in Tu’un Savi, one of the languages of the Mixtec people. Women’s rights feature heavily in her programs. She also translates in court—Tu’un Savi, Spanish, English. The first time he met her, Martínez thought, This woman carries power, light, and darkness, all at once—this is exactly what I’m trying to convey.

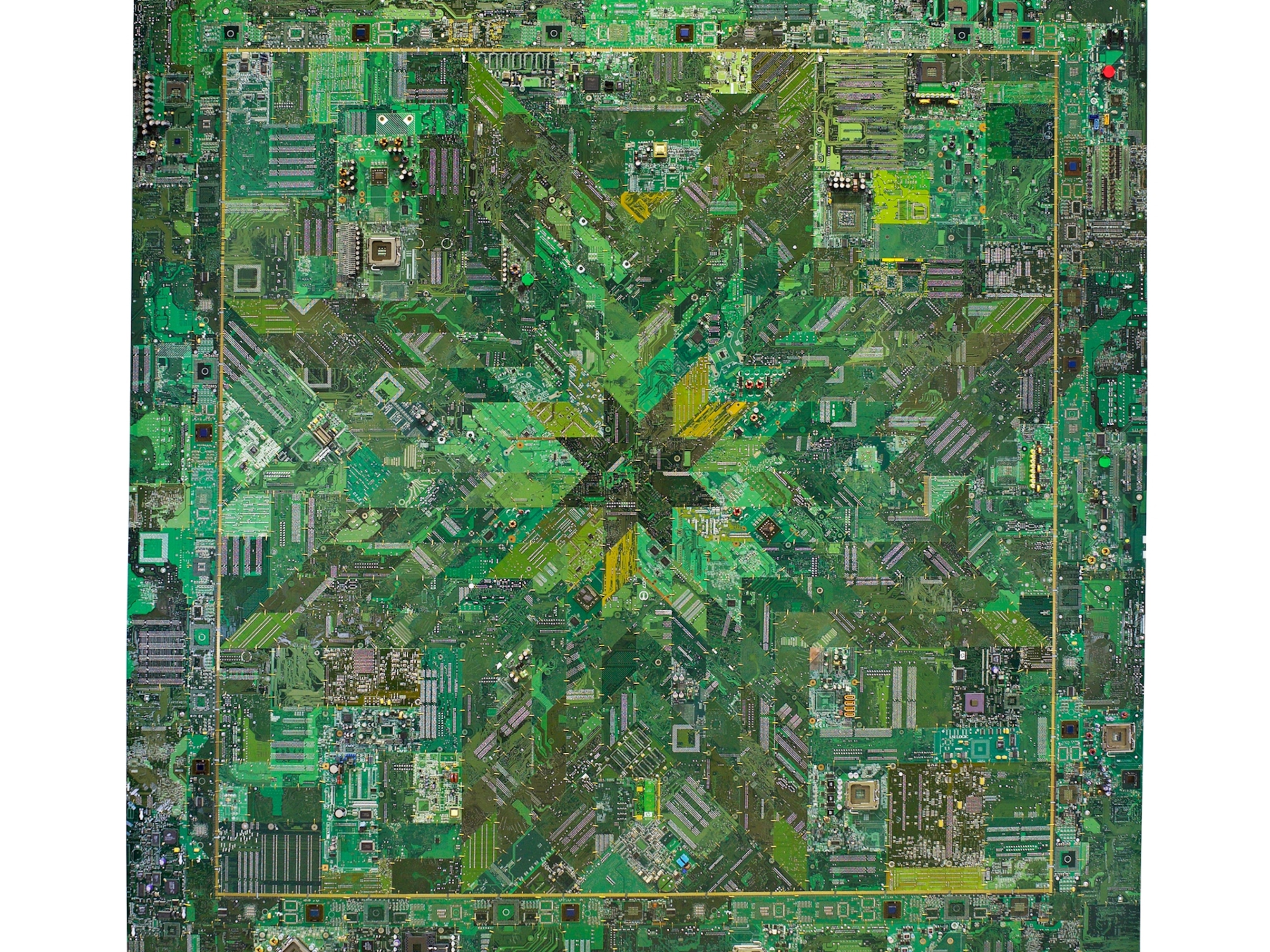

Some years ago Martínez began creating “interventions”—his own photographs, which he prints and then amends with other forms of artistic detail. For this collection, the inaugural National Geographic photo essay in an ongoing collaboration between the magazine and the artist collective For Freedoms, Martínez concentrated his work on Indigenous people—or comunidades originarias, as he prefers to say—from Guerrero, his home state. Why originarias? Because “original communities,” a term Martínez says he learned from Indigenous activists, conveys the dignity of separate nationhood.

The people he photographed for this project, even those now relocated to new surroundings, have legal citizenship in Mexico but ancestral citizenship in ancient states that exist today in language, food, faith, stories passed down over the centuries, and collective understandings of the boundaries that define the world. Meeting originarias like Prudente, Martínez says, forced him to reconsider his ideas about himself: the Indigenous part, the European part, the African part. Sometimes he thinks of Guerrero, deep in Mexico’s south, as a tapestry into which all of Latin America’s complexity has been woven.

“I started this project as an essay on resilience,” Martínez says. “Images of those who have been through trauma and risked their lives to escape violence and support the family they left behind. Images of the immigrants who become the economic pillars for those back home. Images of those people and communities that endure.”

Martínez, a National Geographic Explorer, grew up in a family of artists and once assumed he would become a painter. But when he was a teenager he saw a documentary featuring the work of photographer Josef Koudelka, whose abundant portfolio over the decades includes images from landscapes to war. “It blew my mind,” he says. “When I discovered photography, I fell in love.”

He spent four months on this project, capturing originarias inside and outside their Guerrero home villages. He altered each photograph with multiple pinpricks, speckles of luminosity, a visual hint of what Martínez saw over and over in the women and men who let him come close. “For me, this is the most beautiful thing about each image,” he says. “They emanate light.”

This story appears in the July 2023 issue of National Geographic magazine and is one of eight stories from The Past Is Present project, a collaboration between National Geographic and For Freedoms.

READ THIS NEXT

These Chinese immigrants opened the doors to the American West by Phillip Cheung

Faith fills more than a spiritual void for California’s migrant workers by Brian L. Frank

How Puerto Rico is grappling with its past—to reshape its future by Christopher Gregory Rivera

How has Texas changed in 20 years? She went home to find out by Tanya Habjouqa

Honoring the sacred places they were forced to leave behind by Dakota Mace

These Black transgender activists are fighting to ‘simply be’ by Joshua Rashaad McFadden