How has Texas changed in 20 years? She went home to find out.

After decades as a photojournalist in the Middle East, Tanya Habjouqa turns her lens to the place of her youth, where she says, “If you weren’t part of the privileged few, you were forgotten.”

Tanya Habjouqa experienced one of the first great ruptures of her life when she was four years old. While the family was living in Jordan, her parents divorced—and in the wake of the breach, her American mother brought Tanya and her brother back home to live in Fort Worth, Texas.

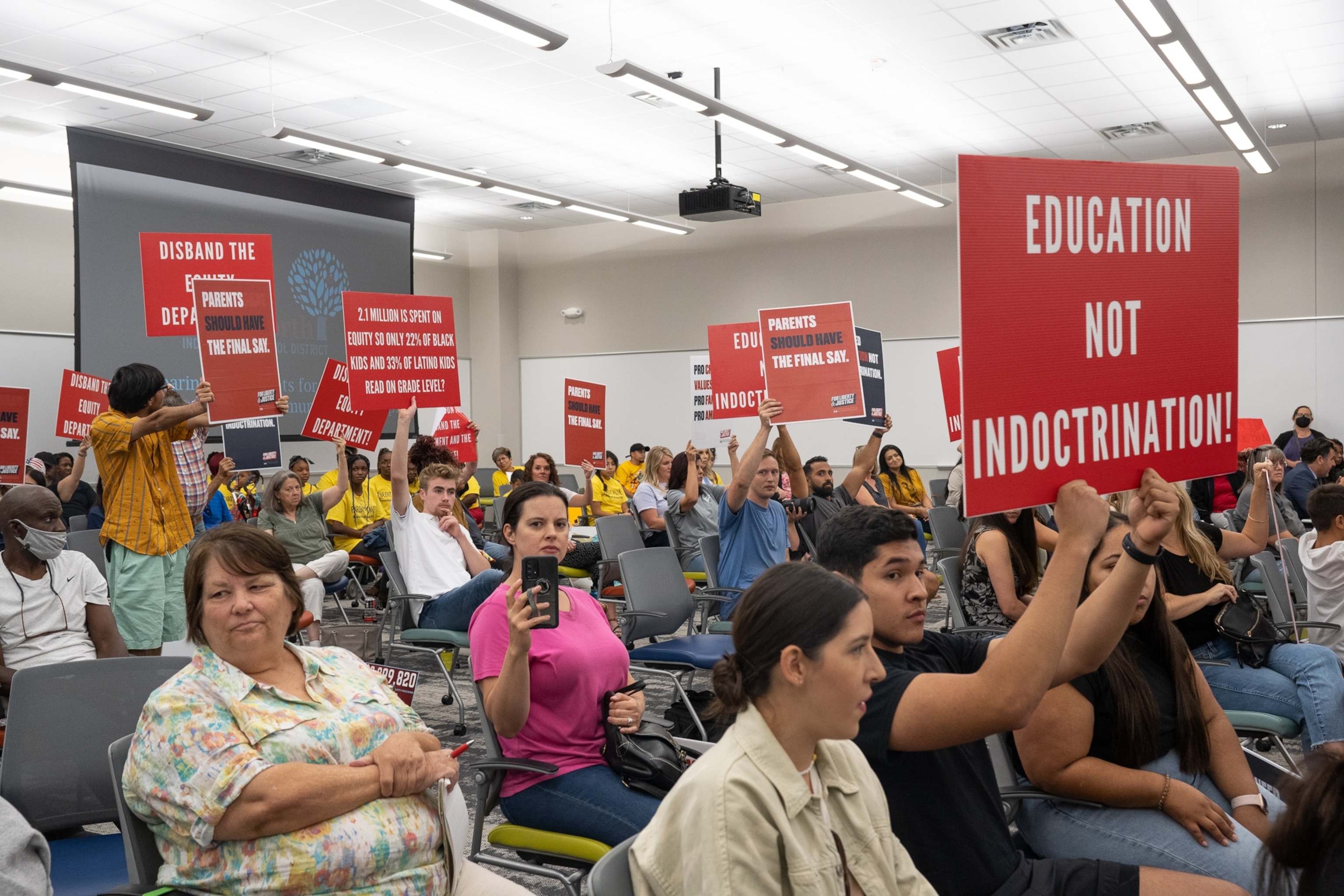

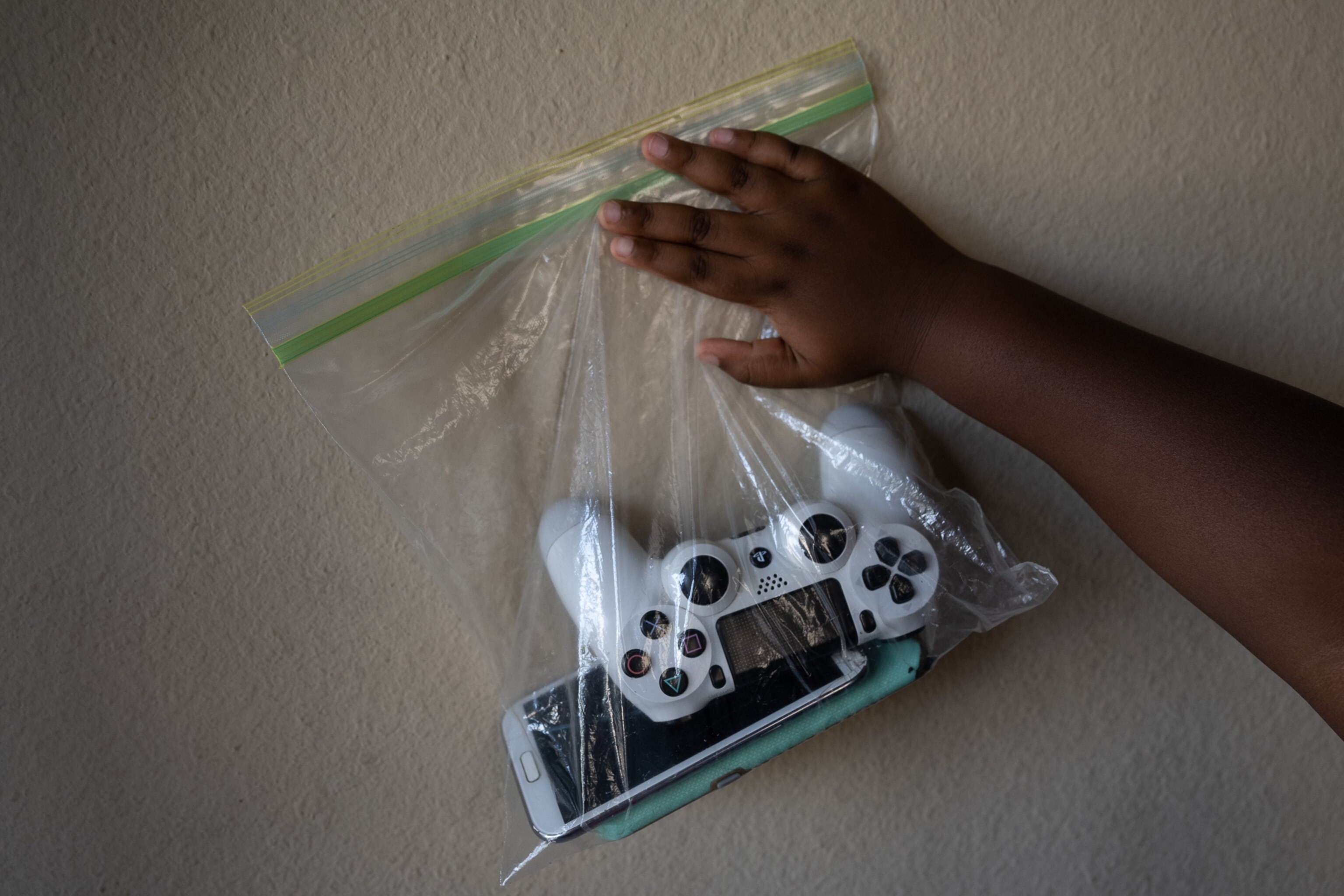

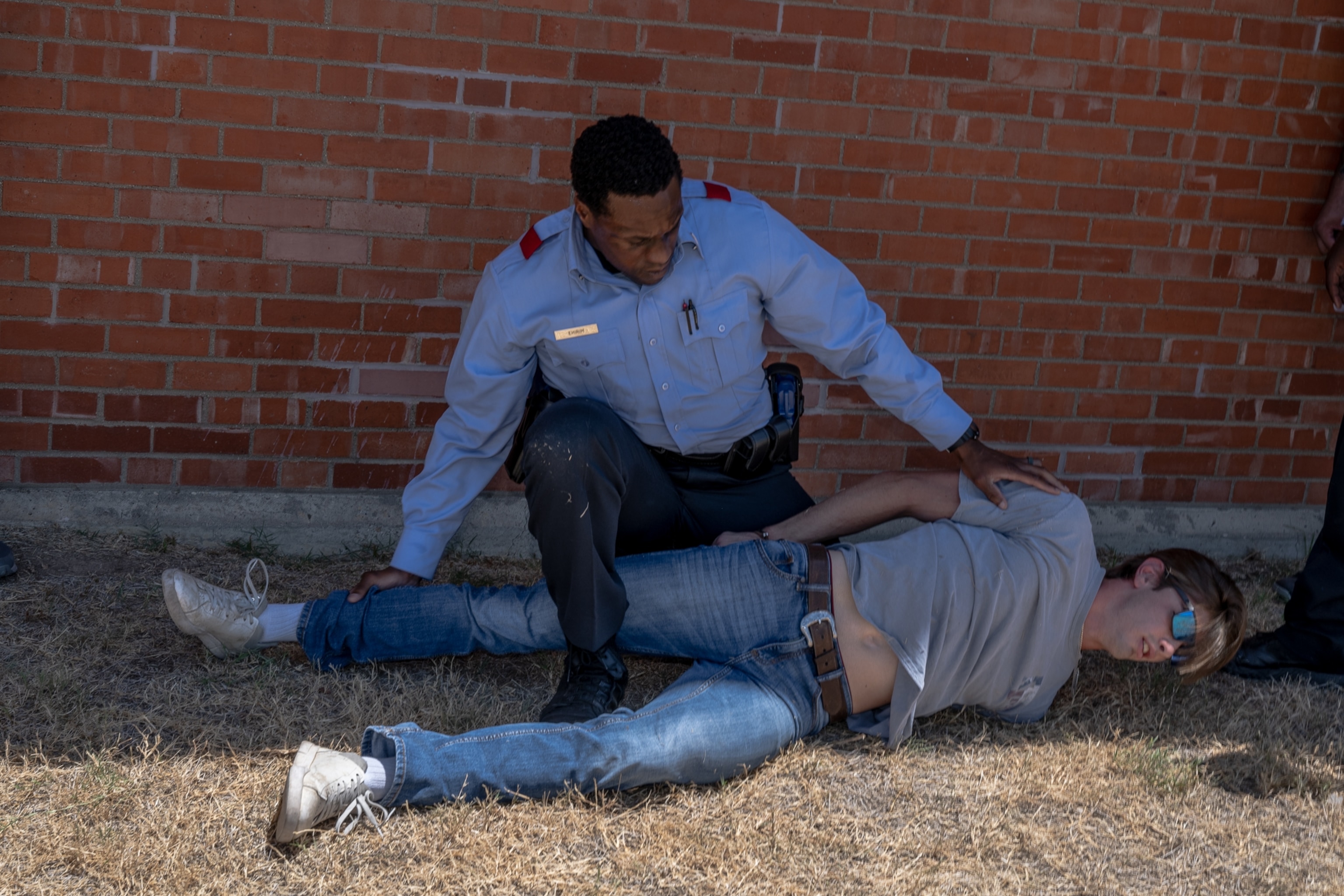

It wasn’t easy for a young multicultural girl to grow up in the heart of Texas in the 1980s and 1990s. She witnessed systemic racism against her Black classmates, and she couldn’t participate in activities like yearbook and photography that seemed to be the sole domain of blonde cheerleaders with wealthy PTA moms.

“If you weren’t part of the privileged few, you were forgotten,” she says.

Tanya left Texas in 2002 and returned to the Middle East, where she spent the next 20 years living in Jordan and Palestine as a photojournalist. While documenting the violence dividing that region, she watched in horror as hierarchies of class and race seemed to become even more entrenched in the U.S. Would she even be able to recognize the Texas of her youth?

She would soon find out: In this photo essay, Tanya reflects on the two months that she spent reconnecting with old friends in Fort Worth and examining the racial and economic fault lines of a place that she had once called home.

This is one of eight stories from The Past Is Present project, a collaboration between National Geographic and For Freedoms.

READ THIS NEXT

These Chinese immigrants opened the doors to the American West by Phillip Cheung

Faith fills more than a spiritual void for California’s migrant workers by Brian L. Frank

How Puerto Rico is grappling with its past—to reshape its future by Christopher Gregory Rivera

Honoring the sacred places they were forced to leave behind by Dakota Mace

‘They emanate light’: Illuminating the lives of Mexico’s Indigenous people by Yael Martínez

These Black transgender activists are fighting to ‘simply be’ by Joshua Rashaad McFadden